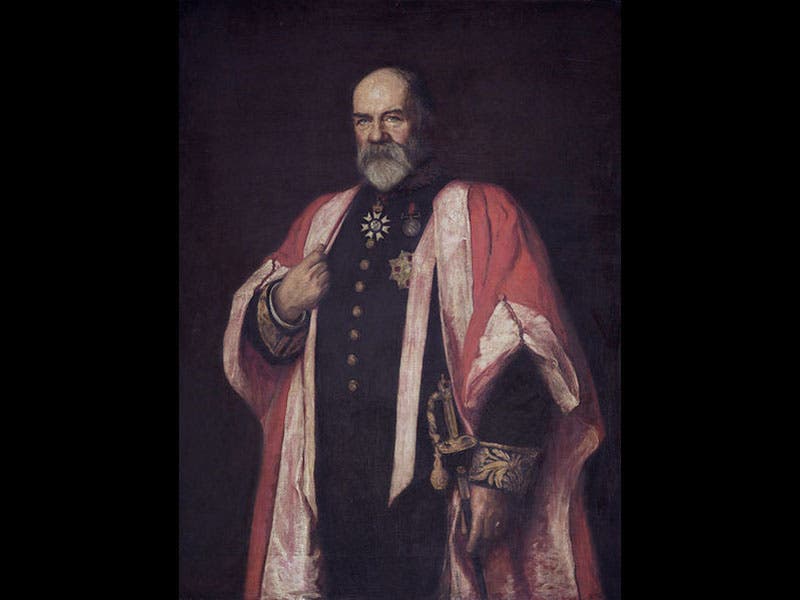

Scientist of the Day - Walter Buller

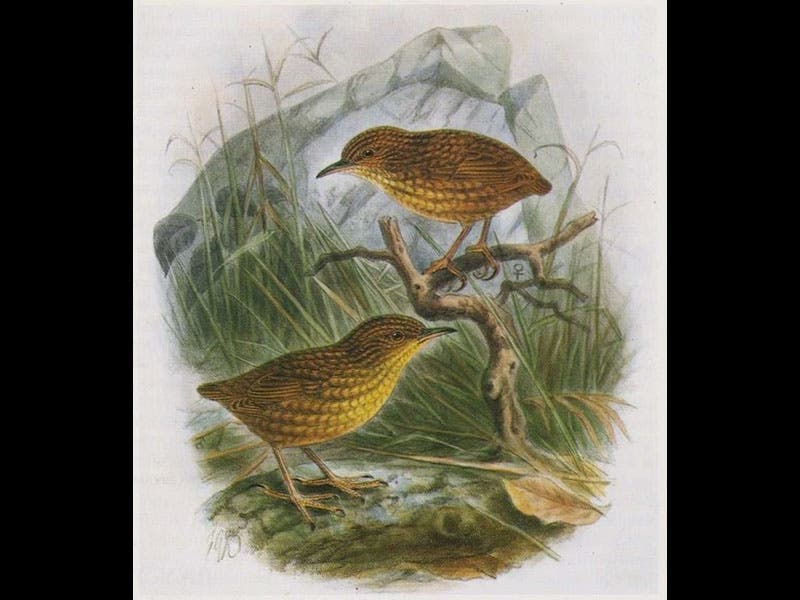

Walter Buller, a New Zealand ornithologist, was born Oct. 9, 1838. In 1895, Buller published an article announcing the discovery of a new species of wren on Stephens Island. This small island lies in Cook's Strait, the body of water that separates North and South Island in New Zealand (see map above). Stephens Island was uninhabited until 1894, when a lighthouse was established and a light-house keeper was hired. The story is that he took with him a cat, and that one day the cat brought back a tiny bird that the keeper--apparently a birder himself-- did not recognize. Buller was notified and the keeper sent him the specimen, which Buller recognized as a new species of wren. He prepared a paper describing the bird, which he called Xenicus insularis, and sent the specimen to London so that it could be drawn by Johann Keulemans, and submitted his paper to Ibis, one of the foremost ornithological journals in England, which queued the paper for publication in the spring of 1895.

Meanwhile, the cat or cats (it seems probable that the original cat was pregnant and gave rise to a whole family of feral cats) continued to bring back wrens, until the keeper had 9 more of them. The keeper realized it might be to his advantage to sell them to someone willing to pay, and so he offered them to the wealthy Baron Walter Rothschild back in England, who had tens of thousands of specimens and eggs at his family estate at Tring, 30 miles northwest of London, and who jumped at the chance to buy the 9 dead wrens. Rothschild immediately wrote a paper and had it read to the British Ornithologists Club and offered his paper for publication in the Club Bulletin. The editor of Ibis notified Rothschild that Buller had already submitted a paper on the bird and had named it, and the paper was scheduled for publication, but Rothschild went ahead and published his description anyway, naming the bird Travseria lyalli (Lyall was the lighthouse keeper), and because his paper appeared first, his name for the bird was valid, and when Buller's paper came out three months later, his proposed name was instantly obsolete, becoming what taxonomists call a junior synonym.

Buller was so furious he could hardly see straight, and for the rest of their lives (Buller died first, in 1906) the two bickered incessantly in print, criticizing each other's descriptions and identifications at every possible occasion. Hell hath no fury like the ornithologist who has been robbed of a discovery! But the real loser in this story was not Buller, or Rothschild, but the Stephens Island wren. By early 1895, within a year of its discovery, the wren was gone, hunted to extinction by the feral cats. It is the most rapid extinction due to human presence in history. Its rapid demise is a very sad chapter in the much larger sad saga of bird extinctions.

In addition to a portrait of Buller and a map of the location of Stephens Island, there are two images of the Stephens Island wren above, both drawn by Keulemans; the first is the one that appeared in Ibis in 1895, and the second, with two wrens, was included in another publication of Buller in 1906.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.