Scientist of the Day - USS Shenandoah

The USS Shenandoah, a U.S. Navy rigid airship or dirigible, first took to the skies on Sep. 4, 1923. It was a huge thing, 680 feet long, powered by 6 Packard gasoline engines. The Shenendoah was our country’s first rigid airship, and the Navy was very proud, but let's not forget that in 1921, Germany had launched a Zeppelin named LZ-121, meaning it had 120 predecessors. So the U.S. Navy was late getting into the game. We have written a post about Ferdinand von Zeppelin and his dirigibles.

The Shenandoah however did have one feature that none of the German Zeppelins had – its gas bags held helium, not hydrogen. Hydrogen was a better lifting agent, since it is the lightest of all gases, but its one shortcoming could (and would) be fatal – hydrogen is extremely combustible. Helium will not burn or explode – it was not called an inert gas for nothing. Germany wanted to build helium dirigibles, but they had no helium – the United States controlled the world's supply of helium and would not sell any to Germany, which after all was our enemy from 1917 until the end of WW1.

The Shenandoah carried the serial designation ZR-1, as this country's first rigid airship. It was not only commissioned by the U.S. Navy, but it was built by the Navy, in the days before sub-contractors. The Navy had a factory in Philadelphia that made all the parts – the frame was manufactured out of duralumin, an alloy of aluminum and copper that was both light and strong. The gasbags were made of gold-beaters skins - the outer membranes of cow intestines – that were cemented onto cotton fabric and varnished. The recipes for the gasbags, as well as for the duralumin frame, were copied from a German Zeppelin, LZ-49, that had been captured in France in 1917. Indeed, the entire design of the ZR-1 was based on the LZ-49.

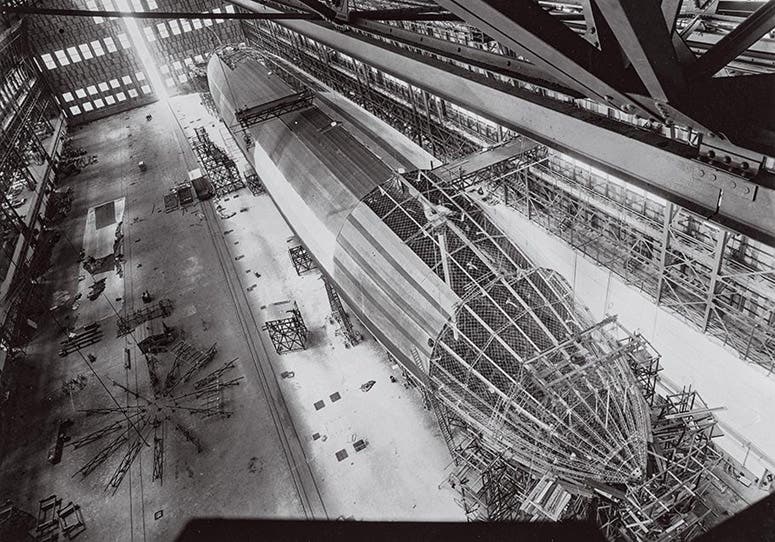

The Philadelphia Naval factory was a large plant, but not large enough to assemble a dirigible. So they built a special hangar, Hangar 1, at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in Lakehurst, New Jersey, that was some 960 feet long and 225 feet tall, and would hold two dirigibles side by side. The hangar was built in 1921 and was the only place in the country large enough to construct and house the Shenandoah. Construction began in 1922 and was completed in late August 1923 (second image). The Shenandoah was inflated in the days before Sep. 4 – it took almost all our country's (i.e., the world's) helium supplies to fill this one airship. Some 400 people pulled it from the hangar on Sep. 4, and ZR-1 immediately took to the air for its first flight, which was successful. It was then pulled back into the hangar for its official christening on Oct. 10. Photos of the christening give one a good idea as to how big this airship was (third image).

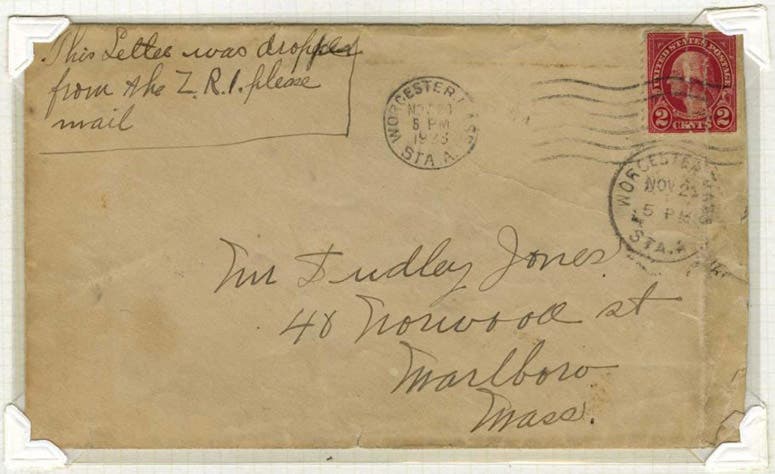

The USS Shenandoah then began a series of test flights along the Eastern seaboard, which occupied the airship for the next year. As a public relations gimmick, it would carry "air mail" to communities along its route. The airmail consisted of letters, usually written by crew members to relatives, that were simply thrown from the cabin to parachute to earth, with the hope that whoever found the mail would take it to the post office for final delivery. I don't know what the percentage rate was for retrieval, but a number of letters were delivered and have survived, and they were indeed great publicity for the rigid airship program. There are examples in the Air and Space Museum, and one – the one we show, postmarked Nov. 23, 1923 – is on display at the National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C. (fifth image).

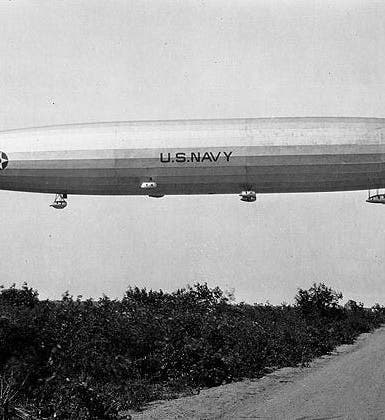

Because it was such a pain to move the Shenandoah in and out of the hangar, a special mooring mast was constructed outside, some 165 feet tall and quite sturdy. The Shenandoah could be attached by the nose to the top of the mast, which could rotate. The Shenandoah then turned like a weathervane in the wind, so it was always downwind, which reduced stresses on the airframe (first image).

In October of 1924, the Shenandoah undertook a cross-country trip, headed for the naval base in San Diego. It was the first such transcontinental trip for a dirigible. The Navy constructed a mooring mast in Fort Worth, Texas, for a half-way stop. By this time, the Navy had converted a ship, the USS Patoka, into a floating mooring station (sixth image). I do not know whether the Patoka made the trip through the Panama Canal to San Diego and then to Tacoma, Washington – if not, they would have had to construct mooring masts there. The entire Shenandoah trip lasted 19 days, and was a great success. The Shenandoah, like our modern-day Goodyear blimp, was a hit wherever it went.

Not so successful was a trip undertaken to the upper Midwest in early September 1925. The Shenandoah encountered a squall line in southeastern Ohio that caused it to rise rapidly; some of the gas cells burst, the airframe twisted and broke apart, and the Shenandoah fell to earth, in three pieces – front, rear, and the control cabin that hung beneath the dirigible. All of those in the cabin – 14 officers – were killed. Most of those in other parts of the dirigible were able to ride the broken-apart aircraft to earth and survived (seventh image). Because helium had been used instead of hydrogen, there were no fires or explosions. But the Shenandoah was finished, one day shy of its second birthday.

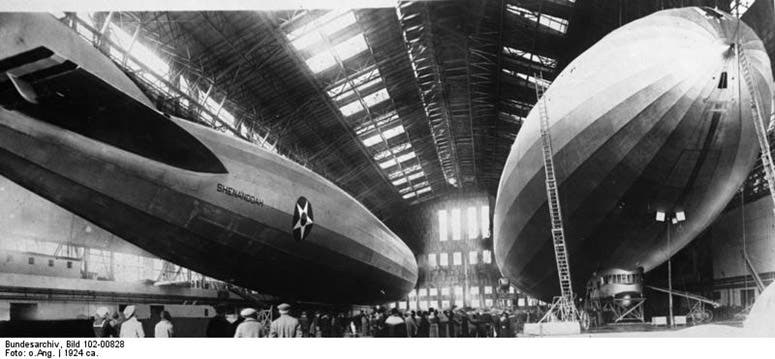

The airship program might have ended right there, but by that time, the Navy had another, USS Los Angeles (ZR-3), which had actually been built by the German Zeppelin factory for the United States as war reparations. For a while it shared Hangar 1 with Shenandoah (eighth image). It remained in service until 1932 and made hundreds of flights. The Navy built two more rigid airships, but by the 1930s, it was clear that the future of aviation lay with heavier-than-air craft. And then, of course, the burning of the German Hindenburg in 1937 – at the very mast where the Shenandoah had moored in 1924-25 – put an end to rigid airships everywhere, hydrogen and helium. Only blimps – non-rigid helium balloons like the Goodyear blimps – remain to serve as reminders of the amazing age of dirigibles.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.