Scientist of the Day - Umberto Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni, an Italian painter and sculptor, was born Oct. 19, 1882. Boccioni was one of the earliest and most influential members of an Italian school of painters known as Futurists. Futurism began in 1909 as a literary movement, with the publication of Tommaso Marinetti's Futurist Manifesto in the Paris newspaper Le Figaro. As movements go, Futurism was a despicable one, at least to a historian like me, in that Marinetti called for a complete break with the past and urged followers to "destroy the museums, the libraries, every type of academy". He furthermore glorified patriotism and war and the destruction it brings and had nothing but scorn for women. A photo shows the founders of Futurism, with Marinetti at the center, and Boccioni next to him, second from the right (second image).

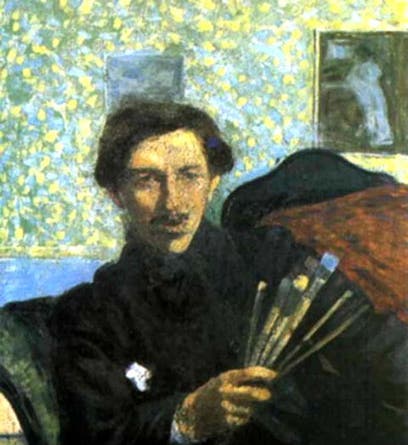

Fortunately, Boccioni had a different view of Futurism and never embraced Marinetti's advice that the art of the past should be destroyed. Boccioni instead saw Futurism as an embrace of the future, which in his mind, meant the embrace of industrialism and machines. He started out as an Impressionist, as his self-portrait indicates (1905, in the Pinacoteca di Brera of Milan; first image). Cubism, in the form of the works of Picasso and Georges Braque, had a great impact on Boccioni and the Futurists. But whereas the Cubists tended to portray stationary objects from multiple viewpoints, Boccioni preferred to keep the spectator still and move everything around him. Boccioni liked to paint moving objects, and since he lived in the Age of the Machine, many of his subjects were drawn from technology. He especially liked the locomotive, the epitome of both mechanism and motion.

In 1911, Boccioni painted Farewells at the Station (third image), the first in a series of three that he called “States of Mind” (all three paintings are in the Museum of Modern Art in New York). The activity of trains and people in Farewells is frenetic, if not pandemoniacal. It is instructive to compare this Futurist view of the railroad with a Romantic painting, in the form of J.M.W. Turner's Rain, Steam, and Speed, 1844 (fourth image, at the National Gallery in London), and an Impressionist view, as in Claude Monet's Arrival of a Train at Gare St.-Lazare, 1877 (fifth image, at the Fogg Museum at Harvard).

Every artistic school since the Industrial Revolution has tried to come to terms with technology and its impact on human life, and each has brought something new and different to the effort. It is not hard to like all three of these examples equally well.

Boccioni did not restrict his attention to machines in motions; he painted other speeding objects as well, such as this horse with rider, in a painting called Elasticity (1912, in the Museo de Novecento, Milan; sixth image).

Boccioni not only founded Futurism, but he became its principal voice and spokesman, and his book, Futurist Painting and Sculpture (1914), helped define the movement. But it did not last, as least not for Boccioni. He entered the Great War in 1916 and within a few months, he was dead, at the age of 34. It is interesting that, despite his belief that the modern world is defined by the machine, his most admired work is a sculpture of the human form, Continuity in Space (1913, but not cast until 1931) in the Museum of Modern Art. Perhaps Boccioni realized, long before the rest of us, that machines come in all forms, some with hearts of flesh, and some with hearts of steel.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.