Scientist of the Day - Ulisse Aldrovandi

Ulisse Aldrovandi, an Italian naturalist and collector of naturalia, was born Sep. 11, 1522, 502 years ago. Aldrovandi was a prodigious publishing machine, beginning 6 years before his death in 1605 and continuing for over 60 years after he was laid to rest in Bologna. The thirteen volumes of what we call his Natural History discourse successively on birds (3 volumes), quadrupeds (3 volumes), fish, insects, serpents and dragons, mollusks and crustaceans, trees, monsters, and fossils. We have written two posts on Aldrovandi, one a general introduction, and the second a digression (with clerihew) on a recently opened (in 2020) exhibition in Italy that involved Aldrovandi. So we have hardly made a dent yet in examining his life work.

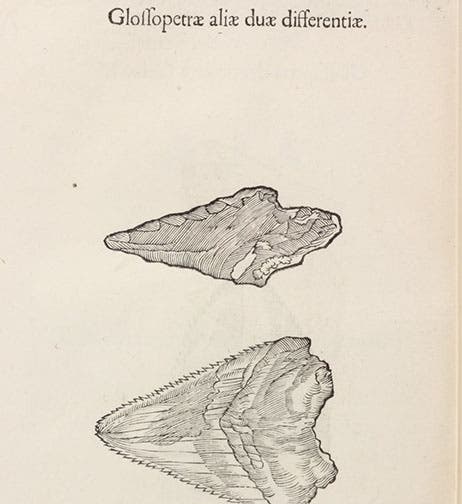

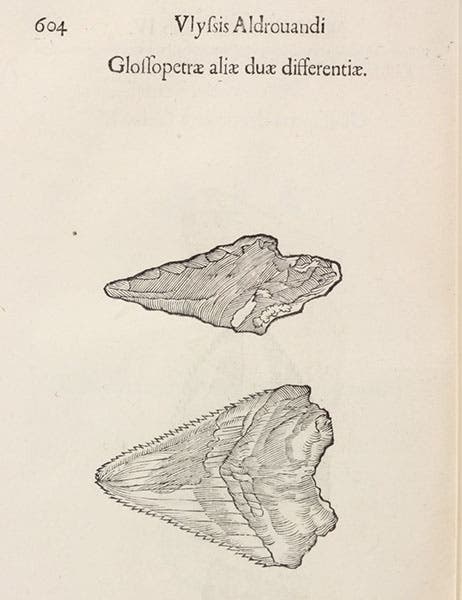

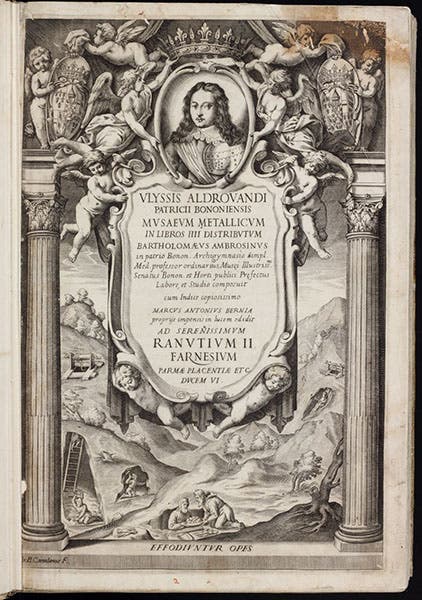

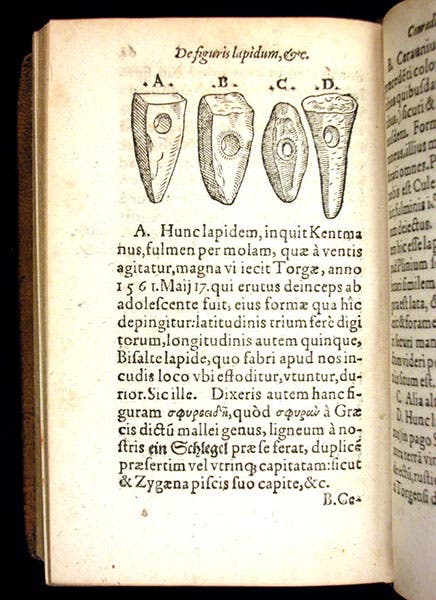

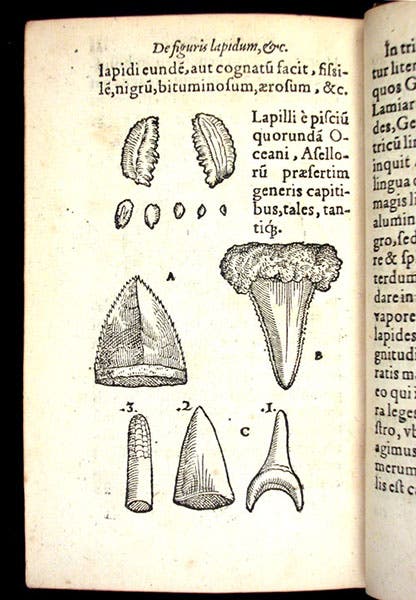

Today we are going to focus on the next-to last-volume of his Natural History to appear, in 1648, 43 years after his death, called Musaeum metallicum, which is about his collection of fossils, and illustrates many of them. Actually, it is more of a universal museum, since many of the woodcuts were borrowed from previous works, such as De omni rerum fossilium of Conrad Gessner (1565). This was the first illustrated book on fossils to be published, and we show two images from that work here, as they form part of the story, depicting some stone tools, which Gessner called ceraunia (thunderstone, fourth image, just below), and a page showing fossil tonguestones (now recognized as sharks’ teeth), which Gessner called glossopetra, Latin for tonguestone (fifth image, below). We are going to refer to a third Gessner fossil, belemnitae, which are the remnant internal bones of cephalopods (not recognized as such in Gessner’s day), and to see that woodcut, you will have to turn to one of our posts on Gessner, where it is the fourth image, and where you can also learn a little more about what the term “fossil” meant to a Renaissance collector.

In Gessner’s book, the three woodcuts of cerauniae, belemnitae, and glossopetrae, appear on leaves 64, 91, and 162; i.e., they have nothing to do with one another. In Aldrovandi’s Musaeum, on the other hand, they are discussed together – in fact, the cerauniae and glossopetrae are intermingled. And that is because Aldrovandi classified things by their shape, by what we now call similitude, or resemblance. Michel Foucault, in his book, The Order of Things, long ago (1966) pointed out that the guiding episteme (organizing principle) of the Renaissance was resemblance (see our post on Foucault). If two things look alike, then that is a sign that they have certain essential features in common – if a liverwort resembles a liver, the simlitude tells us that there is a sympathy between the two, and a preparation made from liverwort may well heal a liver problem in the human body.

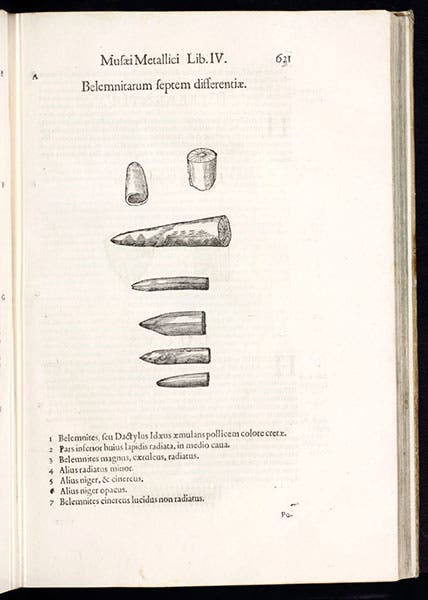

Belemnites, after Gessner but rearranged, woodcut in Musaeum metallicum, by Ulisse Aldrovandi, 1648 (Linda Hall Library)

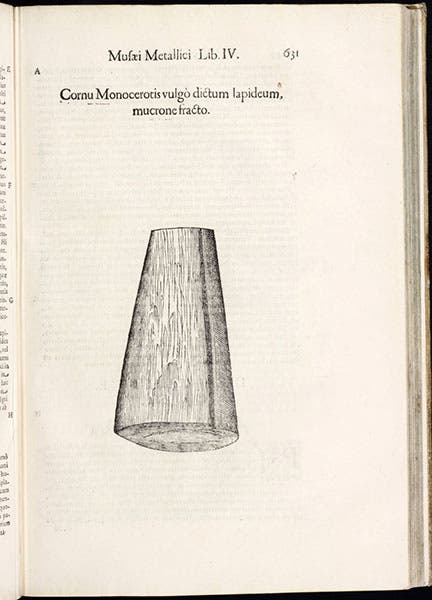

So when Aldrovandi sorted his fossils, he put all those that were pointed and arrowhead-shaped together. The names were incidental. So one woodcut, with the caption “Two kinds of tonguestones,” shows an arrowhead and a tonguestone (first image), while another woodcut, labelled, “Different varieties of thunderstones,” shows two tonguestones and five stone axe-heads (sixth image). The pointy belemnites follow a few pages later (seventh image, just above), as well as the partial horn of a unicorn (narwhal), which looks like a big, broken-off belemnite (eighth image, below).

We would classify things differently today, with similitude way down the list of important criteria. But in the Renaissance, when no one knew what any of these fossils really were, similitude was as good a guide to classification as anything.

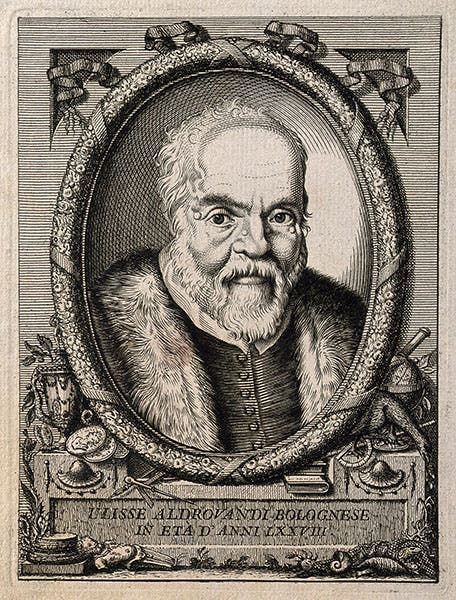

The only portrait of Aldrovandi to appear in any of his 13 volumes was in the first one, on birds (1599), and we showed that in our first post on Aldrovandi (last image at the link). We have one other Aldrovandi portrait in the Library, in a 1682 portrait book, but it has not yet been scanned, so we will save that until we do Aldrovandi’s book on “monstrous things.” For this post, we show an engraving in the Wellcome Collection in London (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.