Scientist of the Day - Tobias Mayer

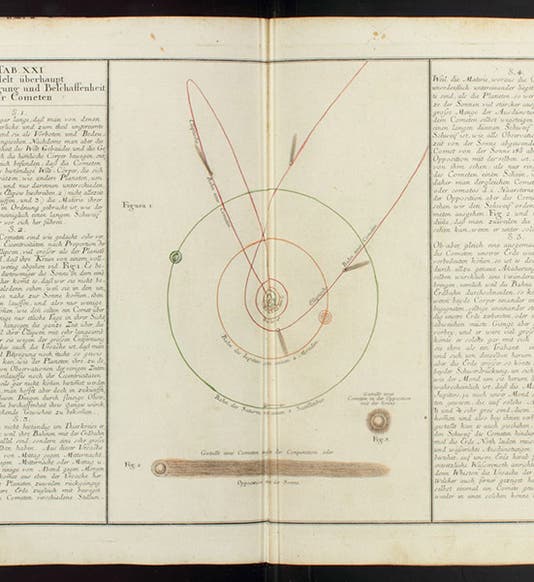

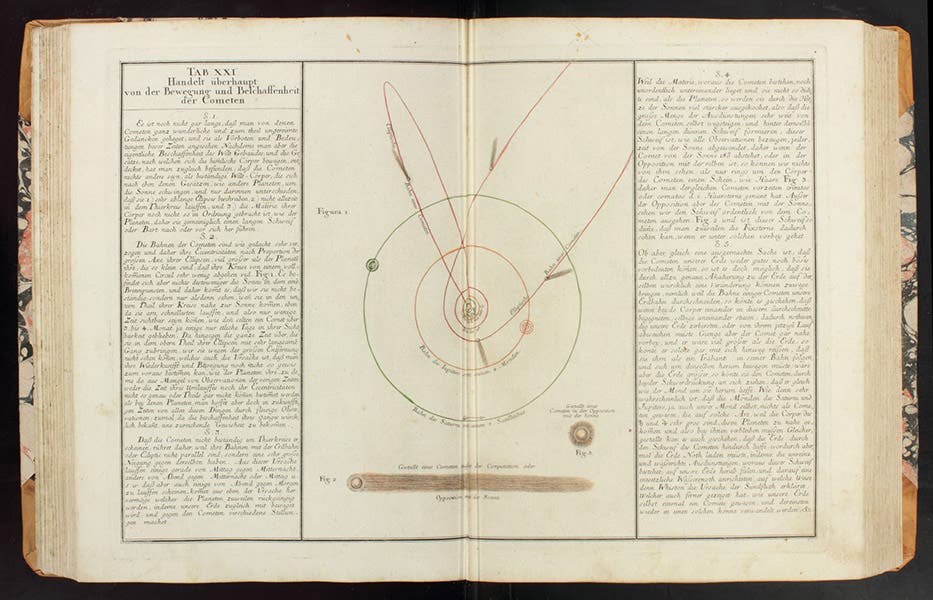

Diagram of comet orbits in the solar system, showing that the tails always point away from the Sun, engraving, in Mathematischer Atlas, by Tobias Mayer, plate 21, 1745 (Linda Hall Library)

Tobias Mayer, a German mathematician and astronomer, was born Feb. 17, 1723, in Marburg, in southern Germany. His father was a wagon builder and well-digger, and his mother a nurse. The family moved to Esslingen, not far from Marburg, when Tobias was young, and where his father died, and then his mother, so Mayer grew up in the town orphanage. Somehow, he managed to get rudimentary schooling and demonstrate uncommon ability in mathematics. He made a map for the town of Esslingen when he was 16, which was engraved and sold, an impressive achievement for someone of his background, and he must have demonstrated even more ability somewhere, for in 1744, when he was 21, he was hired by the Augsburg publisher, Andreas Pfeffel. We will talk more about this association shortly, but we skip ahead briefly and point out that, by 1748, Mayer was a recognized astronomer, working on a lunar map and globe based on measurements with a micrometer. By 1752, he had produced a set of lunar tables so accurate that they were used by English astronomers as the basis for determining longitude at sea using the lunar-distance method. By 1754, still without any university schooling, he became director of the astronomical observatory at Göttingen. He died suddenly, only 39 years old, in 1762. Most of his important work, such as his lunar maps, was published posthumously. We told some of the story of Mayer’s life after 1750, and showed some of his moon maps, three years ago in our first post on Mayer.

But today, we are going to turn back to his two years with the publisher Pfeffel in Augsburg, because a product of that association was a remarkable, indeed almost unfathomable book, with the short title Mathematischer Atlas, and which reads in full (now translating): Mathematical Atlas: in which, in 60 Tables, all the parts of Mathematics are presented, not only for easy repetition in general, but also for Encouragement, especially for beginners, through clear descriptions and figures. Remember that Mayer was 21 years old when he was handed this project, or perhaps, when he conceived it.

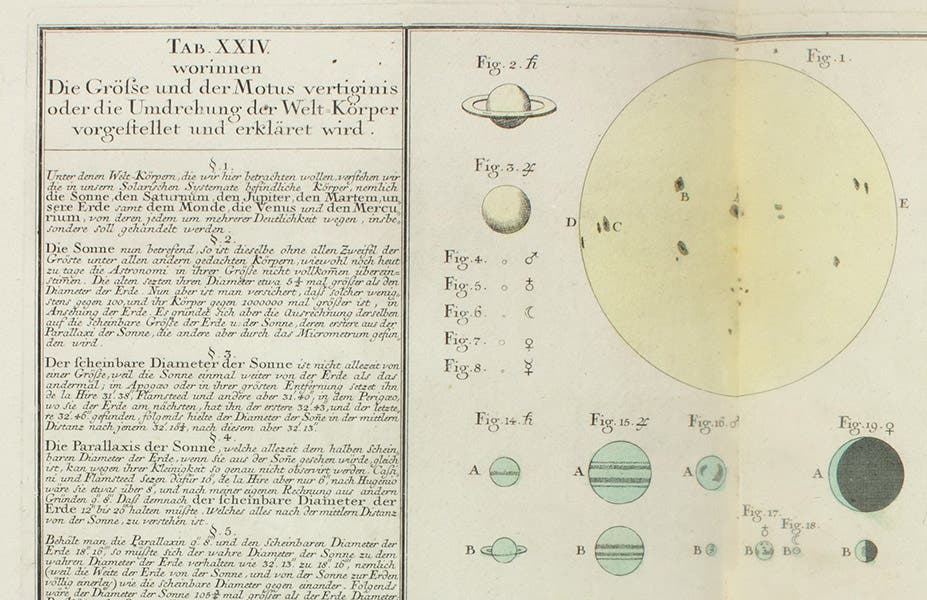

The relative sizes of the Sun and planets, with the faces of some of the planets below, detail of an engraving in Mathematischer Atlas, by Tobias Mayer, plate 24, 1745 (Linda Hall Library)

Mayer’s Mathematical Atlas, published in 1745, consists, as the full title suggests, of 60 large double-page engraved plates, each of which explains some aspect of mathematics, such as geometry or arithmetic, or some mathematical art, such as astronomy, surveying, physics, hydraulics, or pneumatics. The centerpiece of each plate is an image, or, more typically, a set of images, that illustrate the explanatory text on either side. Many of the images are hand-colored. The text, by the way, is engraved, not type-set.

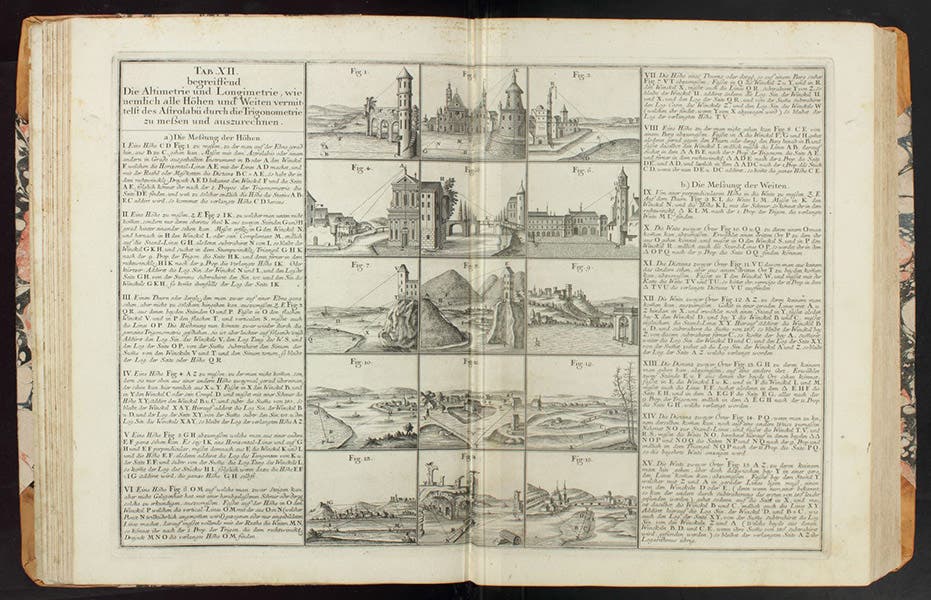

Fifteen different ways of measuring the height of a building by triangulation, engraving in Mathematischer Atlas, by Tobias Mayer, plate 12, 1745 (Linda Hall Library)

One plate, for example, presents information about comets, and the central image gives us a diagram of the solar system, with the planets in their more or less circular orbits, and two comets in elliptical or parabolic paths (first image). The engraving carefully buttresses the point made in the text that the tail of a comet always points away from the Sun, so that when in it is in conjunction with the Sun, it appears to have no tail at all, since the tail points straight back.

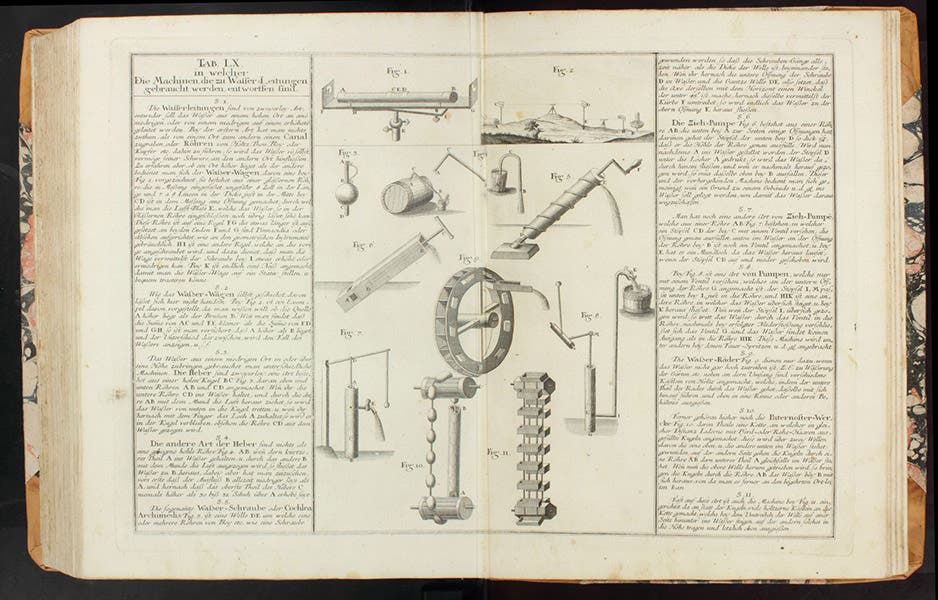

Various machines for raising water, including an Archimedean screw just above right center (fig. 5), engraving in Mathematischer Atlas, by Tobias Mayer, plate 60, 1745 (Linda Hall Library)

There is another plate that shows the solar system without comets, and it is very pretty, with green hand-coloring green, but we pass over it to show a detail of another plate that depicts the planets to scale at the top, and then the faces of the planets below (third image). We show here just a detail of the top left corner, which enlarges the text so that you can see and admire the quality of the engraved script.

The other plates we chose to reproduce in their entirely depict the practice of altimetry (measuring the height of buildings by geometric triangulation; fourth image), and the different methods by which water can be raised to do work (fifth image; this plate happens to be the last of the 60 engravings).

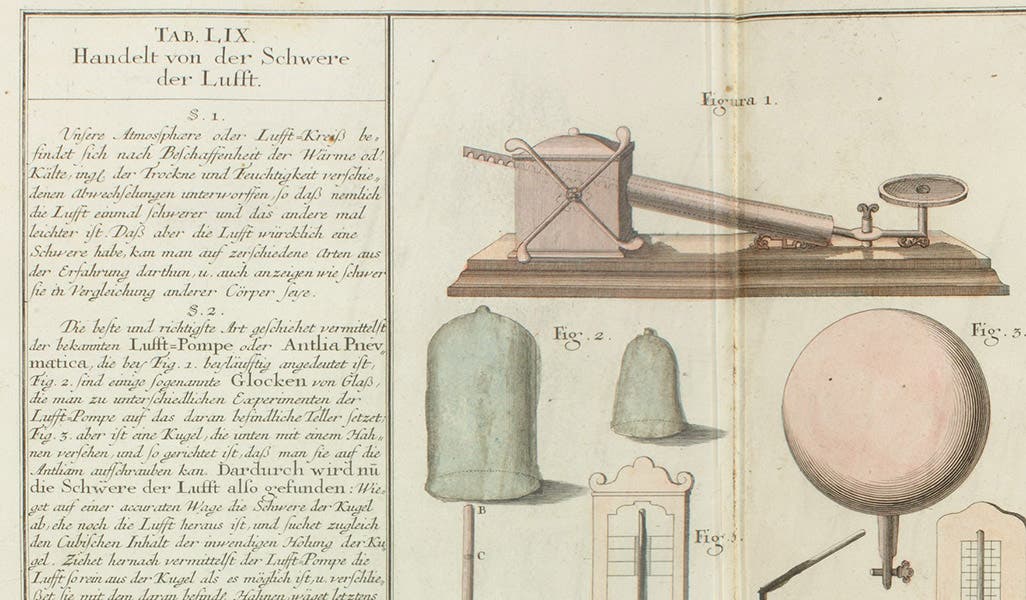

An air pump (vacuum pump), with several bell jars and evacuated glass vessels, detail of an engraving in Mathematischer Atlas, by Tobias Mayer, plate 59, 1745 (Linda Hall Library)

And we show one other detail, this one from a plate about pneumatics, where the top image shows an air pump (what we would not call a vacuum pump; sixth image). It is very similar to the pumps described in our post on Johan Joosten van Musschenbroek

Finally, we note that the book has an engraved title page, upon which a muse with her eyes glazed over seems overwhelmed by the variety of mathematical subjects discussed in the book, many of which are depicted in the engraving (seventh image, below). The plate is signed “I.W. Baumgartner delin[eavit]” and “I.G. Pinz sculpsit,” so it may be that Mayer had nothing to do with its design. But one wouldn’t have thought he could write such a book, either.

Engraved title page, showing a bemused muse being presented with some of the 60 mathematical subjects discussed in the book, engraving in Mathematischer Atlas, by Tobias Mayer, 1745 (Linda Hall Library)

It is hard to determine what the audience was for the Mathematical Atlas. It seems to have been written for budding mathematicians, but they could hardly have afforded such a volume. It is a little too erudite to be a coffee-table book. But someone bought it, for it proved popular enough that Mayer was asked to write an 8-page supplement on more advanced mathematics, which has been bound into our copy.

And the publishing firm of Homann and Son certainly noticed, for they hired Mayer in 1746 to work on mapping, and under their auspices he commenced his micrometric study of the Moon and launched his meteoric (if too short) career.

There seems to be only one portrait of Mayer, on which all other portraits are based, and I do not know where that one is – perhaps in the Tobias Mayer Museum, which occupies Mayer’s birth house in Marburg and a brand new building next door. In our first post, we showed an engraving made from that phantom portrait. For this post, we show an 18th-century painted portrait, probably another copy, which recently sold at auction (second image). I do not know where it ended up.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.