Scientist of the Day - Timothy O’Sullivan

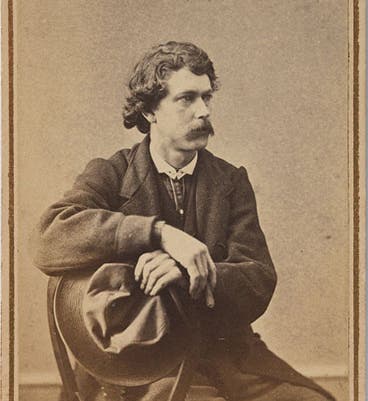

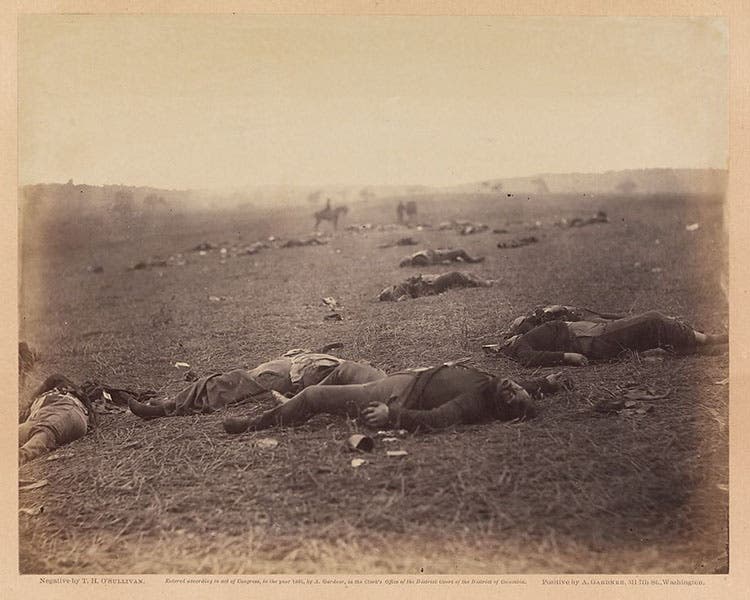

Photographer Timothy O’Sullivan (first image), born c. 1840, died on January 14, 1874. He began his career as an apprentice in Matthew Brady’s New York City studio in the late 1850s, and later worked for Alexander Gardner in the 1860s, traveling with the Union army to photograph Civil War battlefields. One of his most famous war photographs was “Harvest of Death” (second image), a haunting image of Confederate dead at Gettysburg.

O’Sullivan’s connection to science began after the war, when he spent over a decade participating as official photographer on government-sponsored survey expeditions in Panama and throughout the U.S. West. He used a wet plate photographic process (glass plates coated with silver nitrate and then fixed to develop) that had been invented in the 1850s. The wet plate process required a cumbersome traveling darkroom, but it gave photographers two important skills: mobility and the capacity to make unlimited copies of prints.

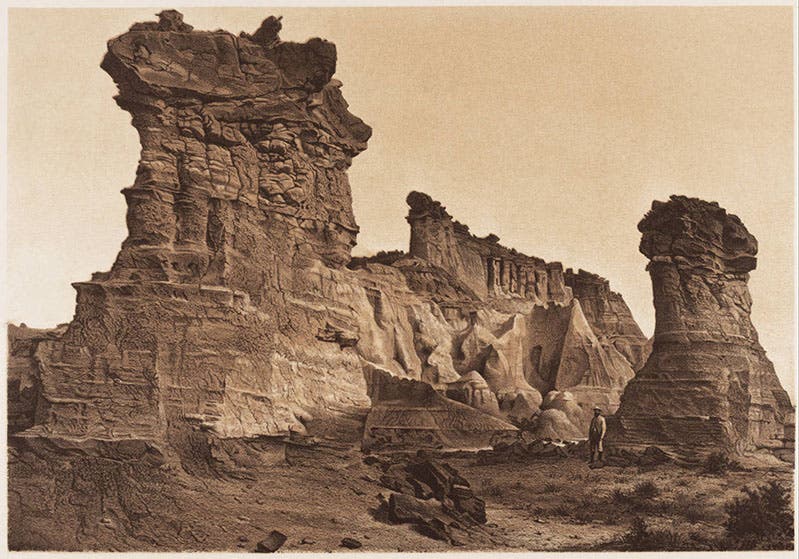

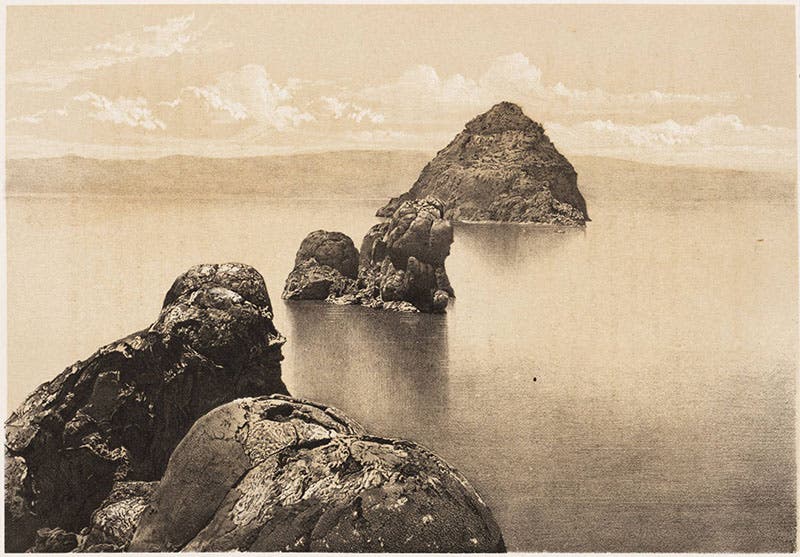

O’Sullivan’s photographs of western landscapes taken during these surveys are notable for both their scientific accuracy and beautiful compositions. Examples of O’Sullivan’s artistic abilities include photographs of a geologic formation in the Washakie Basin in southwest Wyoming (third image) and of tufa rock formations along Pyramid Lake (fourth image) that he captured as a member of Clarence King’s Geological Survey of the Fortieth Parallel in late 1860s and early 1870s. Lithographs, pictured here, were made from O’Sullivan’s photos and printed in survey reports that can be found in the Library’s collection.

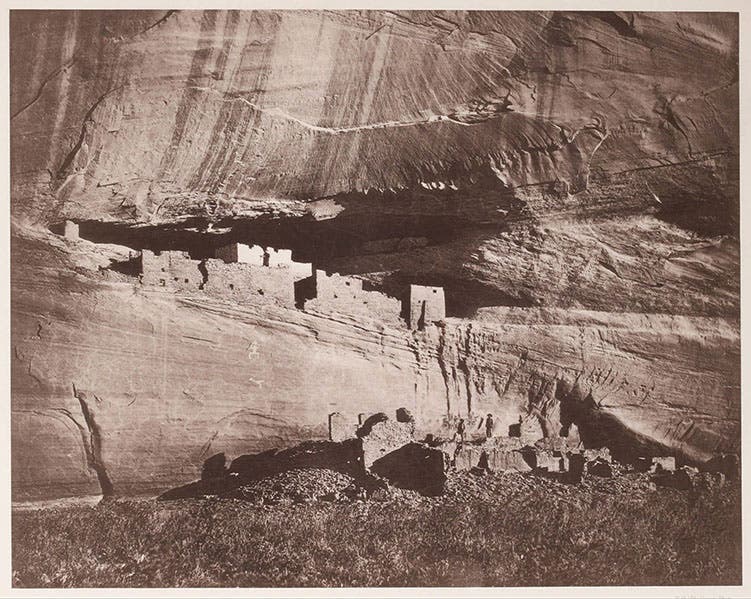

Another example is O’Sullivan’s photograph of ancient Puebloan ruins (fifth image) in Canyon de Chelly in northeast Arizona from 1873 when he was attached to George Wheeler’s Geological Survey West of the One Hundredth Meridian. Though the survey’s objective was to scout future railway locations and to identify natural resources, O’Sullivan led a small entourage into Navajo territory where he photographed the ruins. Note the striations on the canyon walls and the two figures standing below the ruins. You can view an original print of O’Sullivan’s photograph at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. And if the ruins look familiar, you may also remember that Canyon de Chelly was first recorded by artist Richard Kern in 1849, which was highlighted in a previous Scientist of the Day.

In 1880, O’Sullivan became the official photographer for the U.S. Treasury Department. He died two years later at the age of 42 from tuberculosis. Though he had a relatively brief career, O’Sullivan’s remarkable photographic record set a new standard for aesthetics in landscape photography.

Eric Ward is Vice President for Public Programs at the Linda Hall Library. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to warde@lindahall.org.