Scientist of the Day - Time Men of the Year 1961

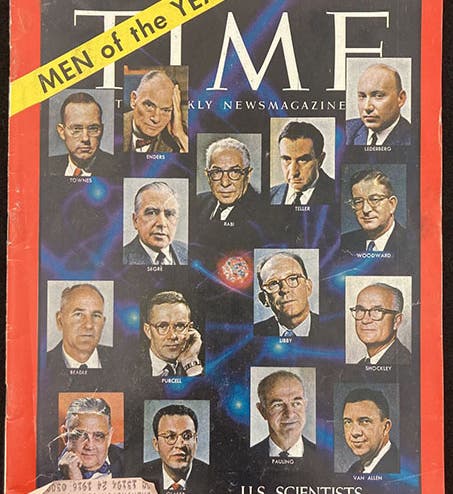

Cover, featuring 15 U.S. scientists as “Men of the Year” for 1960, Time magazine, Jan. 2, 1961 (author’s copy)

The news weekly, Time magazine, was founded in 1923, and in 1928, it inaugurated a tradition of featuring a “Man of the Year” on the first cover in January (Charles Lindberg was that first Man of the Year, for 1927). Only much later (1999) would the honor be re-named “Person of the Year.”

To the best of my knowledge, no scientist was a Man of the Year before 1960. In fact, scientists hardly ever appeared on the cover of any issue of Time. I know of 8 scientists who were featured on a Time cover between 1923 and 1960, a short list that includes Harlow Shapley, Henry Fairfield Osborn, and Edwin Hubble; one scientist who was featured on three separate covers (Albert Einstein); and one who graced four covers between 1934 and 1959, James B. Conant. These are just the ones I have run across – there may be more, but not many more, I would suspect.

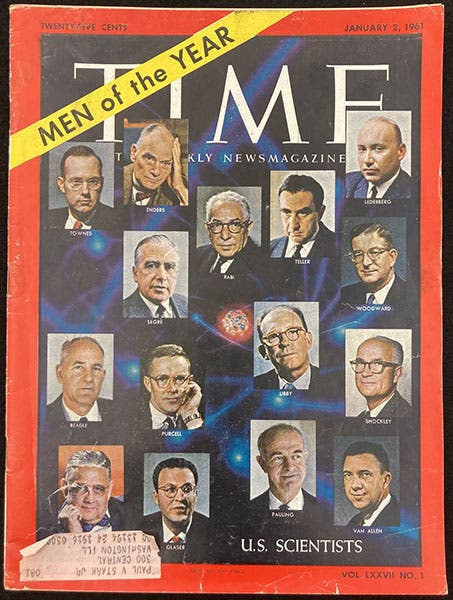

Beginning of cover story, “Men of the Year,” with photo of John Enders at work, Time magazine, p. 40, Jan. 2, 1961 (author’s copy)

So it was something of a surprise when Time featured fifteen scientists as a collective “Men of the Year” on their cover of Jan. 2, 1961 (first image). The men included, from left to right, top to bottom: 1. Charles Townes, 2. John Enders, 3. Joshua Lederberg, 4. Emilio Segre, 5. I. I. Rabi, 6. Edward Teller, 7. Robert Woodward, 8. George Beadle, 9 Edward Purcell, 10. Willard Libby, 11. William Schockley, 12. Charles Draper, 13. Donald Glaser, 14. Linus Pauling, 15. James Van Allen. There were no women scientists in evidence, not surprising for 1961.

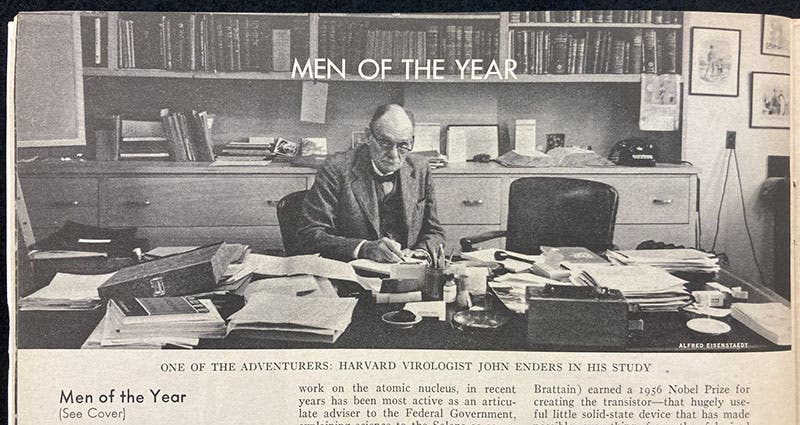

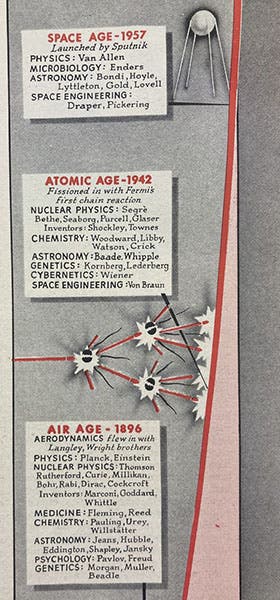

First part of a timeline, “Scientific Explosion,” cover story, “Men of the Year,” Time magazine, p. 41, Jan. 2, 1961 (author’s copy)

We don't have room to discuss each of the fifteen, but among them is the inventor of the maser (Charles Townes, no. 1); the creator of the first measles vaccine (John Enders, no. 2); the father of the hydrogen bomb (Edward Teller, no. 6); the discoverer of radiocarbon dating (Willard Libby, no. 10), the man who unraveled the nature of the chemical bond (Linus Pauling, no. 14); and the discoverer of the Van Allen radiation belts surrounding the Earth (James Van Allen, no. 15, who was on a Time cover all by himself in 1958). There were 10 Nobel Prize winners among the 15, and two more who would collect a Nobel award in the near future. We have written Scientist of the Day features on 7 of these, but that means we have 7 left to go (Schockley will never get one). I am glad the Scientist of the Day post has a future.

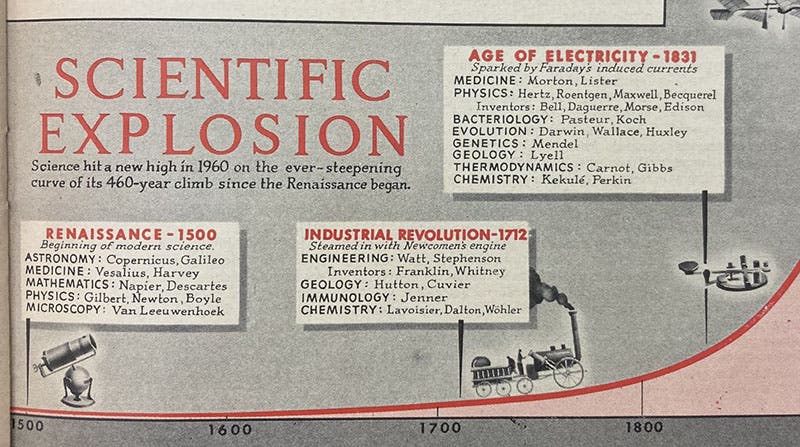

Second part of a timeline, “Scientific Explosion,” cover story, “Men of the Year,” Time magazine, p. 41, Jan. 2, 1961 (author’s copy)

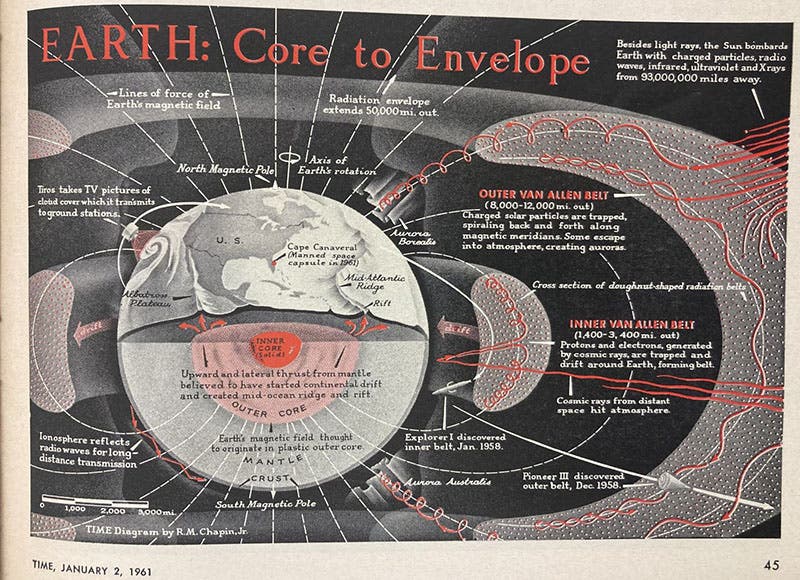

The cover story began with a portrait of Enders at work at his desk at Harvard, and included a short paragraph each on the accomplishments of the 15; a timeline of the “Scientific Explosion” since 1500 (which makes a right-angle turn in the middle, so I broke it into two parts (third and fourth images)), and a diagram of the radiation belts discovered by James Van Allen (fifth image). The timeline does place each of the 15 scientists in a larger context and provides the names of some of their predecessors and peers.

Diagram of the Earth’s Van Allen Belts, cover story, “Men of the Year,” Time magazine, p. 45, Jan. 2, 1961 (author’s copy)

The mere existence of the Time cover is evidence that science had become a more respectable profession by 1961, and indeed that the United States was in the midst of a science revival of sorts, with science education being re-emphasized, and the country working hard to catch up with the Soviets, who had shocked the world with their scientific prowess, evidenced by the success of Sputnik in 1957. So it was nice to learn that the U.S. had 15 eminent scientists who, at least in on Jan. 2, 1961, had a status greater than politicians, athletes, or movie stars.

I have no quarrel with any of the 15 that Time selected – no one knew yet that Townes’ maser was going to pale in significance to the laser, and that Shockley was going to become vilified as a racist and eugenicist. But I couldn’t help asking – who was left out? Who should have been included, but wasn’t? I came up with four omissions that in retrospect seem glaring: James Watson, Richard Feynman, Luis Alvarez, and Hans Bethe. Each of these was at the height of his career in 1961, and each would win a Nobel prize before the decade was out. Hindsight is a dangerous tool and can distort the historical record, but it is still often illuminating.

Nevertheless, it was nice that scientists were finally getting public attention from the country’s leading news magazine and were being portrayed in a positive light. That hasn’t happened all that much since 1961.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.