Scientist of the Day - Tiedemann Giese

Tiedemann Giese, a bishop, theologian, and best friend of Nicholas Copernicus, was born on June 1st, 1480, in Danzig (today Gdańsk, Poland). He left behind only a single published work, which the library does not hold on account of its extreme rarity and focus on Reformation-era theology. Yet because early books often record exchanges between individuals other than the ones featured on the title pages, we find traces of Giese in two of the library’s most valuable 16th-century volumes.

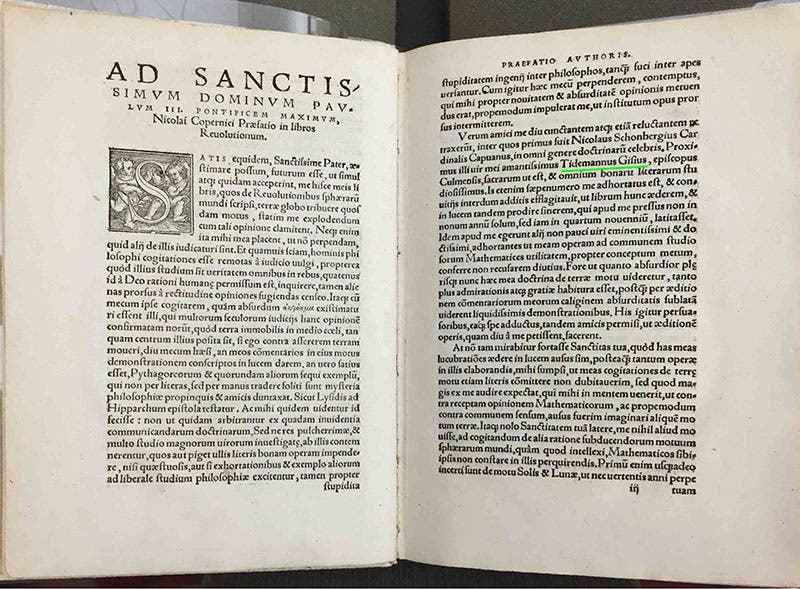

When Copernicus published his novel theory that the Earth orbits around the Sun rather than resting at the center of the cosmos, he credited Giese with repeatedly urging him to finish his book. This passage appears in a prefatory letter to Pope Paul III (second image, below), where Copernicus praises Giese’s great learning in sacred philosophy and the liberal arts and notes that his friend can testify to how many years of repeated encouragement were necessary before he finally published his work. (We featured this passage about the length of time leading up to Copernicus’s 1543 publication in a different context in last month’s post on Maciej Miechowita.) In similar fashion, Giese had thanked Copernicus for urging publication of his own book on disputes over church reform two decades earlier, in his case modestly declaring that the praise for his work had come despite Copernicus being “otherwise a man of acute judgment.”

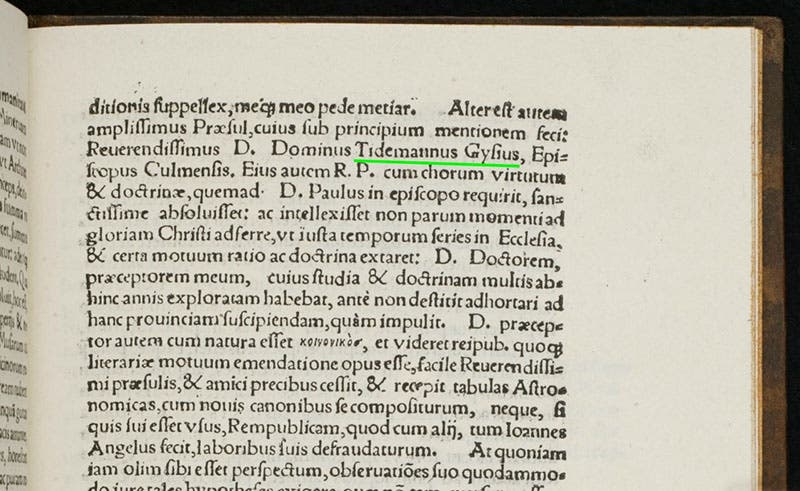

Apart from the time-honored convention of good friends encouraging each other to finally finish writing, Giese and Copernicus apparently engaged in more philosophical debates on the subject of exactly what kind of book Copernicus should produce and how strongly he should foreground his heliocentric theory. We learn these details in the second work to mention Giese from the library’s collections, Georg Rheticus’s Narratio prima (or “first account”), which provided a brief introduction to the heliocentric theory three years before Copernicus’s book came out. At the end of his survey of Copernicus’s work, Rheticus appended a lengthy section praising the people and industries of Prussia, including almost three full pages describing discussions he said had taken place between Giese and Copernicus (third image, below).

According to Rheticus, it was Giese who stressed the importance to the church of having a proper sacred calendar based on correct models of the celestial motions, and when Copernicus suggested that he might simply publish updated astronomical tables without including his more controversial theory of the heavens, Giese argued that this would amount to an incomplete gift. He declared that scholars should not follow the practice of rulers in keeping their overall plans secret in hopes that results alone will be sufficient to win public approval. Instead, he argued that scholars must publicly describe their philosophies in order to permit judgments based on more than “the master said so,” as might occur if Copernicus offered new astronomical tables without providing any theoretical foundations.

It is unclear how much Rheticus’s account should be taken as describing specific conversations as opposed to competing philosophical perspectives, but he clearly portrays Giese as someone who was fully informed about the contents of Copernicus’s work and interested in astronomical practices in his own right. He states that Giese not only possessed his own bronze armillary sphere for making observations but had arranged to have shipped from England a kind of sundial that was “worthy of a prince” and “made by a most noble artisan skilled in the mathematical arts.” This description almost certainly refers to Nicholas Kratzer, the German scientific instrument maker then at the court of Henry VIII (fourth image, below)

There is unfortunately no further description of what Giese’s instrument from England looked like – Rheticus calls it simply a “gnomon” – but Kratzer seems to have been particularly proud of his polyhedral dials like the one he holds in the above portrait by Hans Holbein. Another of these dials features prominently in Holbein’s 1533 painting The Ambassadors, for which Kratzer is assumed to have supplied the large number of mathematical instruments on display (fifth image, below).

In Kratzer’s portrait, the polyhedral dial is shown while still in the process of construction, whereas the one in The Ambassadors appears in a more finished state (sixth image, below). Might the instrument that Rheticus describes examining at Giese’s bishopric castle have been similar to one of these? It seems possible, but we cannot be certain.

We do know, however, that Giese had other direct connections to Holbein. When Holbein began a series of paintings for members of the German merchant community in London in 1532, the most elaborate portrait he made was of Tiedemann’s younger brother Georg (seventh image, below). Historians note that church officials like Giese and Copernicus in Prussian regions were often drawn from local merchant families, but Holbein’s portrait puts this somewhat dry fact on magnificent visual display.

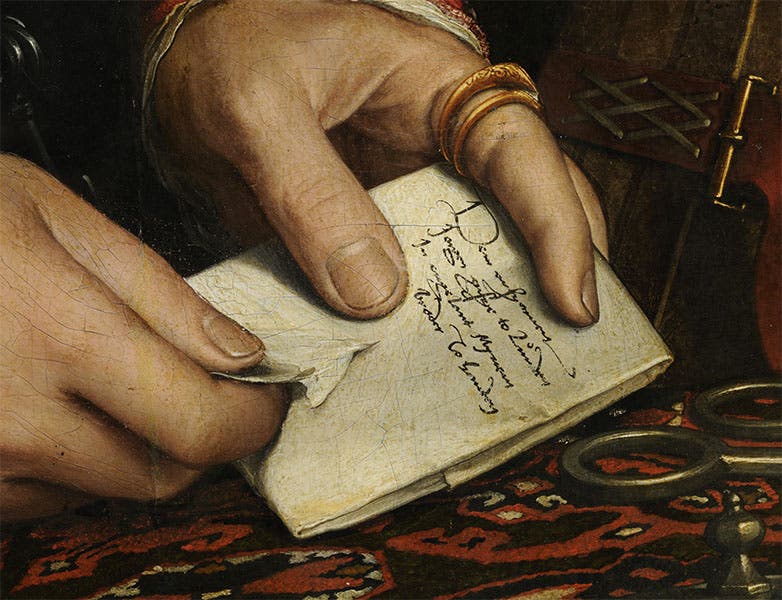

Moreover, if we look closely, Tiedemann is even recorded within his younger brother’s portrait. The painted letter Georg holds in his hands is addressed to “my brother at London in England” (eighth image, below), and since Tiedemann was the only brother still alive when the portrait was painted, this must represent his correspondence. It also suggests how the shipment of Kratzer’s sundial from England was probably arranged.

If we are indebted to Giese for encouraging Copernicus to publish his work, we also owe our most detailed knowledge of Copernicus’s final months to two of Giese’s letters. In December 1542, he wrote to Copernicus’s fellow canon Georg Donner acknowledging receipt of the news that his friend had taken seriously ill and expressing concern that someone “who in good health loved solitude” might now be inadequately cared for despite the fact that “we are all indebted to his integrity and distinguished learning.” Seven months later Giese wrote to Rheticus, thanking him for sending two copies of Copernicus’s book and telling him that Copernicus had died on May 24th after several days of being unconscious. Giese joined Rheticus in expressing outrage over an anonymous preface that had been added to the book – we now know the author was Andreas Osiander, who assisted the printer Johannes Petreius – and he asked Rheticus to forward a letter to Nuremberg’s city council demanding that an amended edition of Copernicus’s work be printed without the offending preface. The council received this letter, and their records note that Petreius responded angrily enough that only a milder version of his answer was to be sent back to Bishop Giese.

Giese also told Rheticus that their proposed new edition of Copernicus’s book should include Rheticus’s biography of Copernicus as well as his defense of the heliocentric theory’s theological soundness. Both of these writings were believed to have been lost until a copy of Rheticus’s theological treatise was unexpectedly discovered forty years ago. Giese himself wrote at least two additional works that have never been found. A manuscript called “Shieldbearer” apparently included a defense of Copernicus’s work and was seen by Jan Brożek, the same Krakow University professor who preserved the two Giese letters quoted above. Another manuscript called "On Christ’s Reign" was bequeathed to Giese’s successor as bishop of Chełmno, who called it pleasant to read but full of “horrible heresies” not in keeping with the Counter-Reformation spirit that followed in the generations after a Catholic bishop had collaborated with a Wittenberg University professor to help usher Copernicus’s work into print.

After eleven years as bishop of Chełmno, Giese served the last two years of his life as bishop of Warmia, where he and Copernicus had spent three decades working together prior to his Chełmno appointment. He died on October 23, 1550, and is believed to have been buried in the same cathedral in Frombork, Poland, where Copernicus was also laid to rest (ninth image, above). While his brother’s portrait by Holbein can still be viewed at the Gemäldegallerie in Berlin, both of Tiedemann’s painted portraits were lost and presumably destroyed during the second world war. We show a pre-war photo of one of them at the top of the page that depicts him in 1544 (first image).

Karl Galle (karlgalle@aucegypt.edu) is a former fellow at the Linda Hall Library and is currently working on a biography of Nicholas Copernicus.