Scientist of the Day - Thomas Sprat

Thomas Sprat, an English cleric and writer, died May 20, 1713, at about age 78; his date of birth is unknown. Sprat was a fellow at Wadham College, Oxford, when the Royal Society of London was founded in 1660 and received its Royal Charter in 1662. Although we now recognize the founding and chartering of the Royal Society as one of the more significant events of early modern science, many Englishmen at the time were not so sure that the Society was such a good thing. Many of the members were what were called "virtuosi," meaning they dabbled in rather than penetrated into the secrets of nature, and the goings on at the weekly meetings, where grown men examined fleas and plum mold with microscopes, and brought in two-headed calves for display, were somewhat suspect.as valuable contributions to society.

In order to put the Royal Society in a better light, the officers made Sprat a Fellow in 1663 and invited him to write a history of the Royal Society, even though an organization only a few years old would not seem to merit historical analysis. Sprat had his account pretty much ready by 1664, but the return of the plague and the Great Fire in 1665-66 put a damper on things (as we can now appreciate), and so Sprat’s The History of the Royal-Society of London did not finally appear in print until 1667; we link here to the title page. In his book, Sprat defended the experimental method and took aim at "enthusiasts" who use flowery rhetoric instead of plain speech in describing nature.

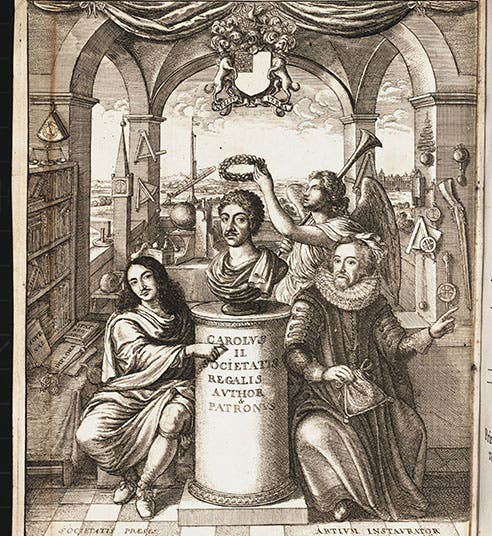

Unless you are a historian of science, you probably have never heard of Sprat, but you might be familiar with the frontispiece of his book (first image). It shows William, Viscount Brouncker, the President of the Royal Society, at the left, and a bust of Charles II, the recently restored King who had granted the Society its Royal Charter, perched on a column in the center. At the top, spread across the landscape, is a panoply of scientific instruments, including a telescope and an air pump. But the most significant figure sits at the right, identified as Artium instaurator, the Restorer of Arts. This is Francis Bacon, whom the Royal Society looked to as their principal forerunner and inspiration. Bacon in the 1620s had called for a complete revamping of natural philosophy, with the emphasis on the collection of facts and the production of experiments, turning away from ancient written authority. Bacon also wrote an unfinished utopian work, the New Atlantis (1626), published posthumously, in which his new society was built around "Solomon's House," a scientific society that met on a regular basis and performed experiments. The Royal Society considered itself to be the real embodiment of the virtual Solomon's House. This frontispiece is often reproduced in historical discussions of the Royal Society, because it illustrates so well the point about the influence of Baconianism on Restoration science in England.

It is a bit of a letdown, then, to learn that this famous frontispiece was actually an afterthought and had originally been designed for a completely different book. A gardener and Royal Society Fellow named John Beale had been intending to write a similar kind of manifesto about the Royal Society, and he commissioned his friend and fellow gardener John Evelyn to design a frontispiece (Evelyn had earlier designed the crest of the Royal Society, which appears in Sprat's History just before the frontispiece, and also on the frontispiece itself, at the very top), and Beale went so far as to have the frontispiece engraved by Wenceslaus Hollar and printed, even before his book was finished. When Beale heard about Sprat's undertaking, he gave up his own, and it was decided at the last minute to add the Beale/Evelyn/Hollar frontispiece to Sprat's book. There was only one problem – Beale's book was going to be a small quarto, and the engraving was designed to fit that format, making it too large for the octavo-size History by Sprat. But they went ahead anyway, and so the copies of Sprat’s History that contain the frontispiece have the engraving folded in some fashion to fit the book (in our copy, the plate was folded in at the left and then trimmed off at the bottom). At least half of the known copies do not have the frontispiece at all – we have two such copies – another good sign that the decision to include it was made late. We are glad that our most recently acquired copy has the engraving – in fact, we made quite sure that it did when we bought it in 1998 from New York City bookseller Jonathan Hill.

After writing the History, Sprat had a long career as a churchman, becoming Canon and then Dean of Westminster, and Bishop of Rochester. He is buried in a chapel at Westminster Abbey. There is a posthumous portrait of Sprat at Wadham College, Oxford (second image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.