Scientist of the Day - Thomas Shadwell

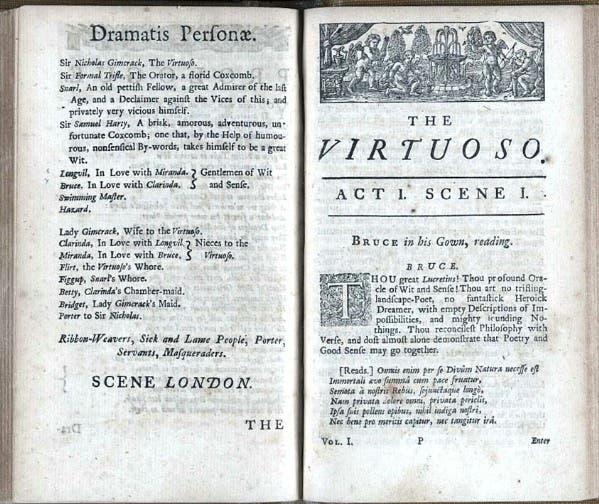

Thomas Shadwell, an English playwright, died Nov. 19, 1692, at about age 50. In May of 1676, Shadwell’s play The Virtuoso opened at the Dorset Garden Theater in London (third image, below). The play was a satire on the fledgling Royal Society of London, chartered in 1662 but having a rough time with its public image in the 1670s. The lead character in the play is Sir Nicholas Gimcrack, who plays "the Virtuoso," a 17th-century term often used for an experimental scientist, usually with the connotation of being wealthy, and a dabbler. His companion is Sir Formal Trifle, “the Orator, a florid Coxcomb,” according to the Dramatis personae (second image).

During the course of the play, Sir Nicholas undertakes a variety of experiments and investigations. Early in Act II, a young man named Bruce, who is courting one of Gimcrack’s nieces, is told that Sir Nicholas is learning how to swim. He wonders aloud where the water might be, and the following dialogue ensues:

Lady Gimcrack: He does not learn to swim in the water, sir.

Bruce: Not in the water, madam! How then?

Lady Gimcrack: In his laboratory, a spacious room where all his instruments and fine knacks are.

Longvil (a young man courting the other niece): How is this possible?

Lady Gimcrack: Why, he has a swimming master come to him.

Bruce: A swimming master! This is beyond all precedent. (Aside) He is the most curious coxcomb breathing.

Lady Gimcrack: He has a frog in a bowl of water, tied with a packthread by the loins, which packthread Sir Nicholas holds in his teeth, lying upon his belly on a table, and as the frog strikes, he strikes …

Longvil (aside): This is the rarest fop that ever was heard of.

At the very end of this scene, which includes their entering the lab to see Sir Nicholas lying on a table, imitating a frog swimming, Longvil asks:

Have you ever tried it in the water, sir?

Sir Nicholas: No sir, but I swim most exquisitely on land.

Bruce: Do you intend to practice in the water, sir?

Sir Nicholas: Never, sir. I hate the water. I never come upon the water, sir.

Longvill: Then there will be no use of swimming.

Sir Nicholas: I content myself with the speculative part of swimming; I care not for the practice. I seldom bring anything to use; ‘tis not my way. Knowledge is my ultimate end.

A little later in Act II, Sir Nicholas recounts an experiment in which he transfused blood from a mangy spaniel into a healthy bulldog, and vice versa:

Sir Formal: Indeed, that which ensu’d upon the operation was miraculous, for the mangy spaniel became sound and the bulldog mangy.

Sir Nicholas: Not only so, gentlemen, but the spaniel became a bulldog, and the bulldog a spaniel.

Other experiments and demonstrations follow. Sir Nicholas wonders why a plum is blue, looks at one with his magnifying glass and discovers that the blue color is due to thousands of tiny creatures. On a further occasion, in Act V, Sir Nicholas tells Longvil that glowing rotten meat will lose its luminescence when placed in a jar evacuated by one of his pneumatic engines.

Longvil: Will stinking flesh give light like rotten wood?

Sir Nicholas: O Yes…I myself have read a Geneva Bible by a leg of pork.

Not only is this all very funny, but interestingly, every one of the topics lampooned in the play – blood transfusion, the glow of rotten meat – had been the subject of a paper by some member of the Royal Society. To find experiments to ridicule, Shadwell had to go no further than the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. It was presumed by all the play-goers that Nicholas Gimcrack was intended to represent Robert Hooke, who had indeed looked at the blue on plums with his microscope. Hooke saw the play on June 2, 1676, and he wrote in his diary: "Dammed Doggs. Vindica me deus : People almost pointed."

Shadwell had other successful plays, but none with the staying power of The Virtuoso. He became Poet Laureate in 1689, when the new monarchs, William and Mary, fired the sitting laureate, John Dryden. Since Dryden and Shadwell were bitter enemies, and regularly targeted each other in their plays and poems, this must have given Shadwell much pleasure, but he was only able to gloat for 3 years before death put an end to his laureate.

We do not have a copy of Shadwell’s play in our library, and I am not sure any original copies of the play survive – I have never seen one or heard of one. Our image of the Dramatis personae comes from a copy of Shadwell’s collected Dramatick Works, 1720, at King’s College, London.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.