Scientist of the Day - Thomas Salusbury

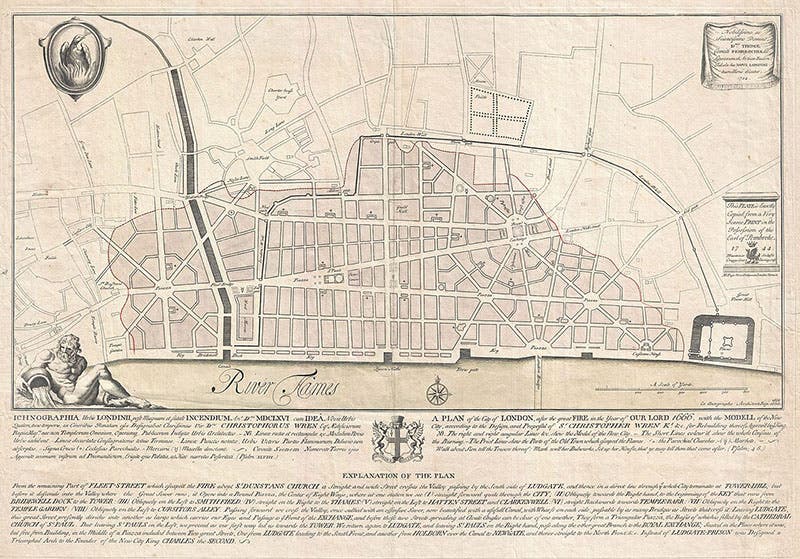

Very early in the morning of Sep. 2, 1666, a fire broke out in a small bakery in London. The fire spread and could not be contained, and by the time it finally subsided three days later, much of central London had been gutted, with the loss of 88 churches, some 13,000 houses, and the centerpiece of London, St. Paul's Cathedral. The fire and its aftermath have some interesting science connections. One of our principal sources on the course of the fire is the diary of Samuel Pepys, who spent much of those four days checking on the progress of the fire from a boat on the Thames. He returned home long enough to bury his store of wine and a wheel of “Parmezan” cheese in the back yard. Pepys was not much of a scientist, but he was later President of the Royal Society of London, and his name is on the title page of Isaac Newton's Principia (1687; second image at our post on Newton). Three other members of the Royal Society submitted plans for the rebuilding of London – Robert Hooke, John Evelyn, and Christopher Wren. A 1742 copy of a 1724 copy of Wren’s rebuilding proposal survives, showing that he imagined new London as a new Rome, with piazzas everywhere (second image: you can see a zoomable version here). But all the plans came to naught, for while authorities deliberated, Londoners rebuilt the city all by themselves without any architectural guidance. So Wren turned his attention to rebuilding the parish churches (he reconstructed 51 of the 88 destroyed), and to designing and erecting a new St. Paul's, which he managed to complete within his lifetime. We discussed and illustrated some of this in our post on Wren.

The merchants who suffered most from the fire were the booksellers, many of whom had moved their entire stock to St. Paul's for safety, only to see it go up in flames when the cathedral's lead roof melted down. One stack amongst the hundreds of titles so affected included the recently printed copies of volume 2 of Thomas Salusbury's Mathematical Collections and Translations of Galileo. Volume 1 had been printed in 1661 (we have a copy in our History of Science Collection), and volume 2 (dated 1665) was nearly ready for distribution when the fire struck. So far as can be determined, only 8 copies of volume 2, part 1 survived, and of volume 2, part 2, which contained Salusbury's biography of Galileo (the printing of which was apparently not quite completed), only a single copy escaped the conflagration. We can semi-track that copy over the centuries, although no one managed to pin it down long enough to read the biography and comment on it, and then it entered the library of George Parker, the 2nd Earl of Macclesfield, and no one read it there either. Indeed, several scholars went looking for it in the library at Shirburn Castle in Oxfordshire, the family estate, and could not find it. But in 2004, the entire Macclesfield collection went up for auction, and when it was inventoried, sure enough, the volume with the biography of Galileo was there. One enterprising scholar, Nick Wilding, flew to London and persuaded Sotheby's to let him look at it, but when the volume was sold in 2006, it went to a private buyer, and no scholar has seen it since (so far as I know). There is hope for its re-emergence, since Salusbury had quite a different view of Galileo’s trial, seeing it not as a matter of religion and science, but as an act of revenge by Pope Urban VIII, who hoped, Salusbury said, to get back at the Duke de’ Medici by crushing his court favorite. Not a very likely story, perhaps, but one we would like to have the opportunity of reading again.

We have published a post on George Parker, the 2nd Earl of Macclesfield, and his library, and also a post on Paolo Foscarini, whose banned treatise embracing Copernicanism was included by Salusbury in volume 1 on his Mathematical Collections; you may see a page from the book at our post. You will not see a portrait of Salusbury, there or here, because no portrait has survived,

To return to the Fire, the historical events gave rise to a children’s ditty, as has often happened; it is a round called “London’s Burning,” which you can hear at this link. At some point, a variant arose, with the focus on Samuel Pepys and his diary notes on the Fire. It doesn’t really have a title, so we will call it by its first line, “Samuel Pepys.” As you will hear, if you watch the video, it is historically rather loose, as Pepys did not die in a fire, but rather of gout. But the performance I link to, recorded at the BBC Proms in 2008, is most compelling, I am not sure why, perhaps because of the two-syllable pronunciation give to the word “fire,” or perhaps because it is such a forceful arrangement. Among the accompanying still photos, a wheel of Parmesan makes an occasional appearance, a sly reference to Pepys’ emergency back-yard burial. One wonders: did Pepys ever go back and dig it up?

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)