Scientist of the Day - Thomas Grubb

Thomas Grubb, an Irish optical craftsman and telescope maker, died Sep. 19,1878, at the age of 78. We have profiled many telescope makers in this series, including Alvin Clark and his son Alvin Graham Clark, Joseph Fraunhofer, and John Brashear, and Thomas Grubb surely belongs among such company. It is not surprising that the 19th century should have seen a boom in telescope production, since observatories, both public and private, were springing up everywhere. Some observatories wanted to own the largest refractor or reflector in the world, and Alvan Clark & Sons were happy to supply such, for the likes of the Lick Observatory (36-inch refractor) and the Yerkes Observatory (40-inch refractor). But most observatories could not afford nor did they desire a huge telescope. A 12-inch refractor can be quite a satisfactory telescope, if well-made and well-mounted, and that was the kind of instrument that the Grubb Telescope was happy to supply. Based in Dublin, it was run for 40 years by father Thomas, and then was taken over by his son Howard, who brought the firm into the 20th century.

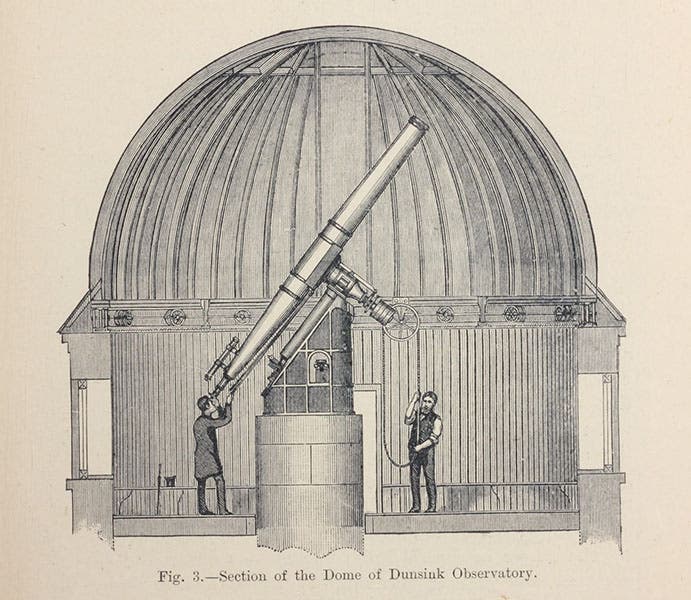

Not surprisingly, being a Dubliner, Thomas started out supplying telescopes and mounts to Irish observatories. We published a post last week on J.L.E. Dreyer, and mentioned that he worked at three of the great Irish observatories, first at Birr Castle in central Ireland, then at Dunsink, near Dublin, and then at Armagh, in Northern Ireland. Thomas Grubb supplied instruments or mounts for all three institutions. When William Parsons, Lord Rosse, in the 1840s was planning his huge 72-inch reflector at his estate at Birr, (the mirror for which he cast and ground himself), he was aided in designing the piers and the support for the mirror by Thomas, who had only recently entered the telescope business. In the 1860s, Grubb acquired a lens from Thomas South, and built a 12-inch refractor for the Dunsink Observatory (third image). And he constructed a 10-inch refractor for the Armagh Observatory, which was moved into a new dome in 1885, and which Dreyer used to confirm nebula positions as he was producing his New General Catalogue of Nebulae (see our post on Dreyer). This telescope has been well preserved and restored, as recent photographs indicate (first image)

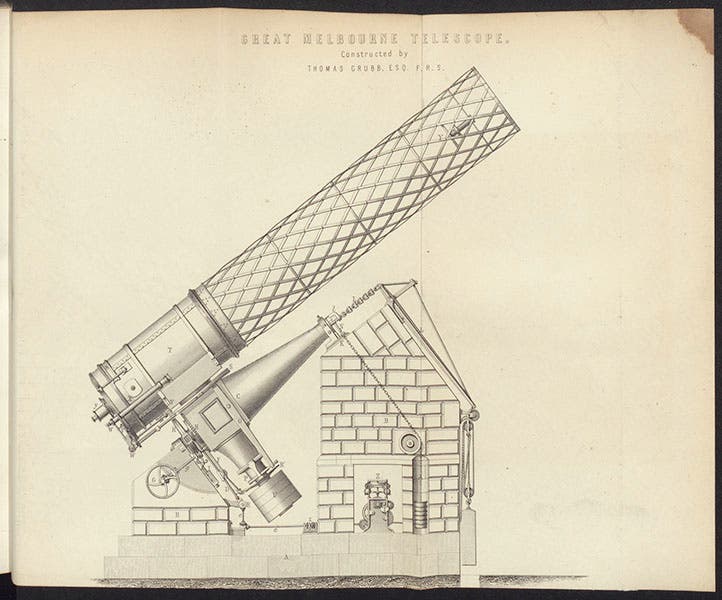

Grubb did build a few large telescopes. Melbourne Observatory in Australia wanted a large reflector, like that of Lord Rosse, but they wanted it fully maneuverable, on an equatorial mounting. Grubb provided them with a 48-inch equatorial with a beautiful mount. When it was installed in 1869, it was the largest telescope in the southern hemisphere, and the second largest in the world, after the 72-inch Leviathan of Lord Rosse (fourth image).

Grubb's son Howard joined the family business and ensured its continuation into the 20th century. Thomas and Howard combined to design and build a large refractor for the Royal Observatory in Vienna. This was a 27-inch giant, one inch larger than the 26-inch refractor that Clark & Son had just provided for the U.S. Naval Observatory. It was opened in 1878, just before Thomas died, and is now part of the University of Vienna (fifth image).

There seems to be only one surviving photograph of Thomas Grubb, which we show as our second image. After his death in 1878, he was buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery, Harold's Cross, County Dublin, Ireland, where the headstone of Thomas and his family still stands (sixth image).

For those of you who like to visit historic telescopes (as I do), Thomas Grubb is supposed to have provided a refractor to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, sometime in the 1830s or 1840s. But I can find out little about it, and have uncovered no images at all. If it still exists, please let me know, especially if you have a photo in hand. And if you know of other Grubb telescopes in the United States, I would love to be informed.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.