Scientist of the Day - Thomas Eakins

Thomas Eakins, an American artist, was born July 25, 1844, in Philadelphia. He was what is called a realist painter, choosing subjects, such as rowers and boxers, that were not commonly seen in American art of the time. We include him as a Scientist of the Day because three of his best-known works portray surgeons, two of them at work in the operating theater, and one painting, not well-known at all, is a powerful portrait of a physicist. Plus, we throw in a bonus, a painting of a sculler that not only includes a self-portrait, but shows that Eakins could have earned a living (perhaps) recording feats of civil engineering.

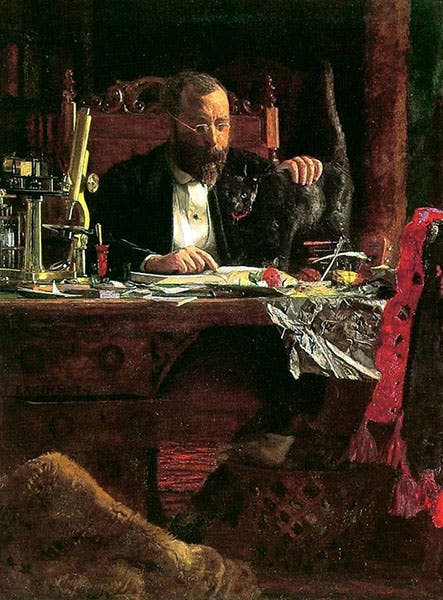

Eakins' first attempt at painting a physician or surgeon was a simple portrait of his old anatomy professor at Jefferson Medical College, Dr. Benjamin Rand (third image). It shows Rand at his desk, stroking a cat and reading a book, rather than presiding over an operation, but it is a powerful portrait nevertheless. When the College decided to sell off its two famous Eakins paintings some years back, this one was bought by Alice Walton and went to the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, where you may see it on a day trip from Kansas City, if you like. You can learn a little more about this transaction in a post we did some years ago on Benjamin Rand.

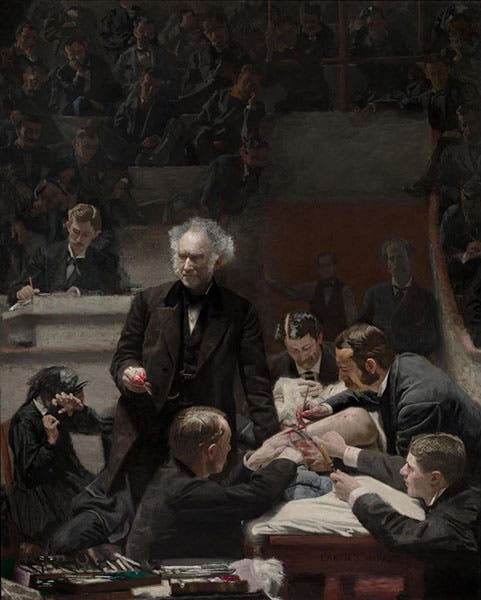

The Portrait of Benjamin Rand does not quite prepare us for The Gross Clinic (1875), which is not only a riveting poirtrait of Dr. Samuel David Gross, but a chilling glimpse of a surgical setting in late 19th-century America, as a young man undergoes an operation on his leg, while scores of medical students, and the patient's weeping mother at left, look on (fourth image). This painting is realism personified, and a little hard to look at, especially in person, as the painting is some 8 feet tall. It was the other painting sold by Jefferson Medical College in 2007, and was originally going to leave Philadelphia for Bentonville, until a consortium of Philadelphia museums and patrons came up with the funds to keep it in town. It is now jointly owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Denied a chance at Dr. Gross, Alice Walton got Dr. Rand instead, and saved over forty million dollars in the process. But she did miss out on what many consider the finest 19th-century American painting of them all. We showed a detail of Eakins' painting, a close-up of just Dr. Gross, in our post on Gross.

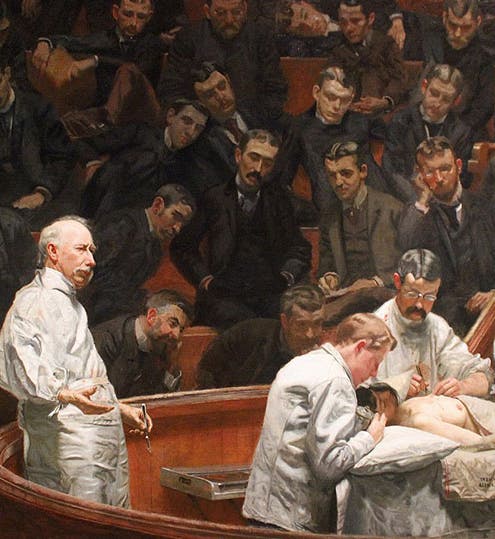

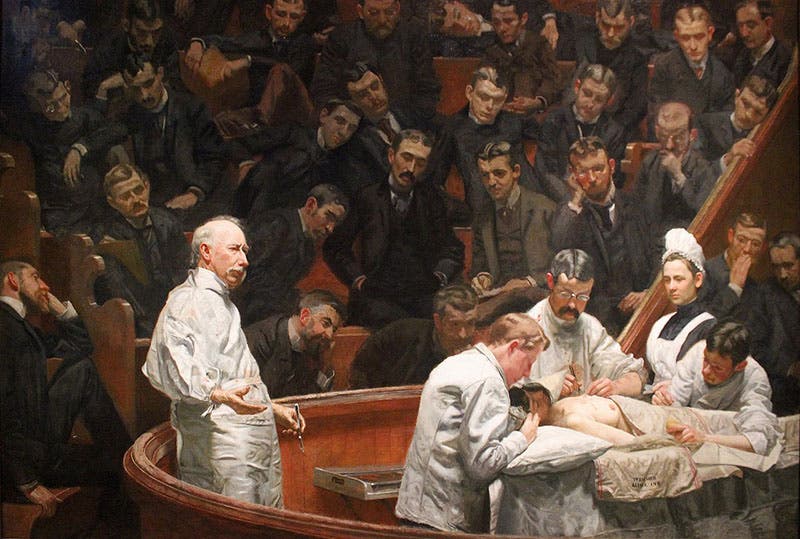

Almost 15 years later, Eakins painted The Agnew Clinic (1889) (first image). It depicts a mastectomy operation on a woman, and was commissioned by three graduated classes from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School to honor a retiring professor, Dr. David Hayes Agnew, who is shown standing at the left. It also portrays what is claimed to be the first trained operating-room nurse, Mary Clymer, who is now even more famous than Dr. Agnew, since her diaries detailing her nursing experiences survive. This painting is so painstakingly done that every one of the medical students in the audience has been identified. The only person unrecognized in the painting is the patient, which is perhaps just as well.

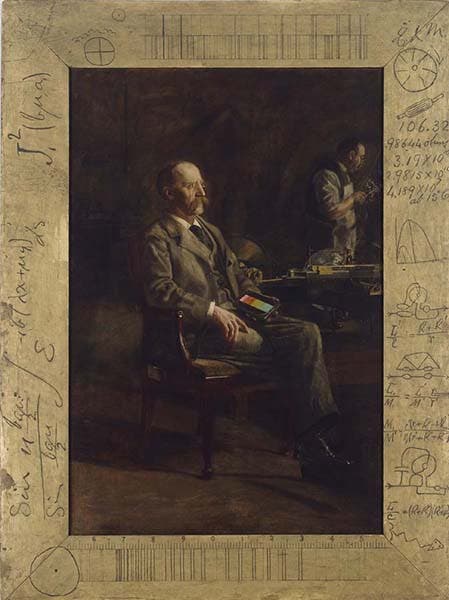

The other portrait we will consider today is different in many ways from these three, since it portrays a physicist, Henry A. Rowland, who was the first professor of physics at John Hopkins University in Baltimore (fifth image). Rowland's specialty was spectroscopy, and in particular, in making the finest diffraction gratings in the world. You can spread a beam of light out into a spectrum in two ways – by passing it through a prism, or by bouncing it off a piece of glass or metal ruled with very closely spaced engraved lines. Rowland invented a machine that could create thousands of parallel engraved lines per inch, which produced extremely precise spectra. Eakins portrayed him with one of his diffraction gratings in his hand. As a special touch, Eakins engraved the frame with a variety of spectra, instruments, and equations relevant to the field of spectroscopy. The painting is in the collection of the remarkable Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass.

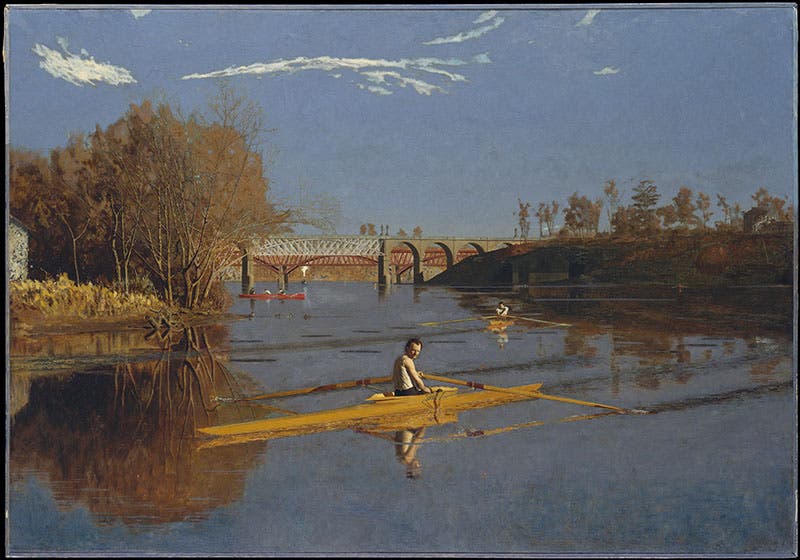

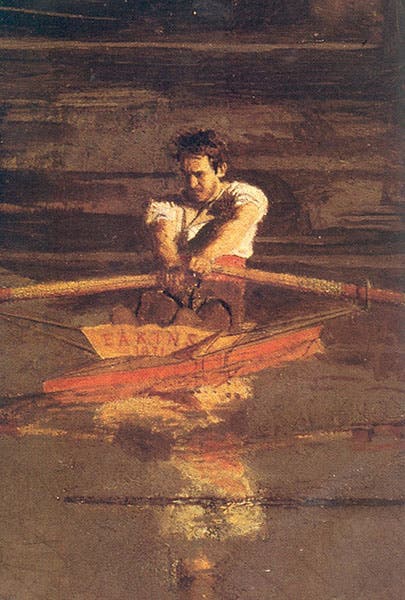

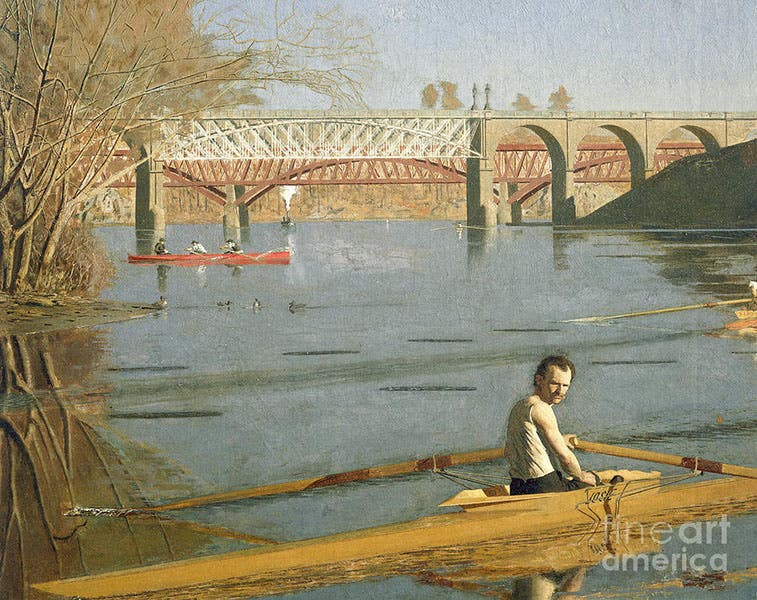

Our last Eakins painting is the first one of his that survives, Max Schmitt in a Single Scull (1871), now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC (sixth image). It is not overtly related to science or medicine, but I include it for two reasons. One, it contains a self-portrait of Eakins as a young man; he is the second sculler, at the oars of his own shell, which is signed with his name (seventh image). Second, the painting depicts in the background the Girard Avenue Bridge and the Pennsylvania Railroad Connecting Bridge across the Schuylkill River (eighth image). These are very precisely painted and unnecessarily accurate, except to a realist painter. You can look up both bridges on Wikipedia and see what I mean.

I try never to end any entry on a down note, but here I must, for Eakins’ reputation has been acquiring an increasing amount of tarnish of late, as evidence of sexual misbehavior and possible abuse of his students has emerged. He was fired from his position of professor of art at the Pennsylvania Academy in 1886, with no explanation, and it has been argued that this was the result of sexual misconduct. I wish his artwork could stand alone, a separate set of entities unconnected to Eakins’ moral character. But it cannot, really. The Gross Clinic loses much of its appeal for me in the light of these recent revelations. And that is sad.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.