Scientist of the Day - Thomas Alva Edison

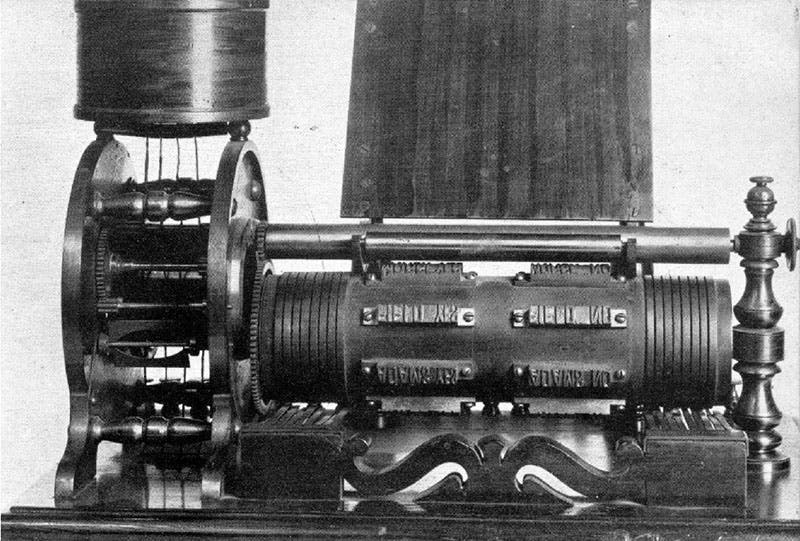

Thomas Edison, an American inventor and entrepreneur, died Oct. 18, 1931, at the age of 84. He had been born on Feb. 11, 1847, in Ohio, but he grew up in Port Huron, Michigan. He was educated by his mother, and with one brief exception, he never attended a formal institution of learning. As a boy, he earned money selling newspapers on the train to Detroit, including one paper that he wrote and printed himself. When he was 15, he happened to save a young lad from being run down by a train, and in gratitude, the boy’s father taught Edison how to be a telegraph operator. Telegraphy was the technological rage of the 1860s, eliciting all sorts of inventions to speed the rate of transmission, which was the principal problem facing the expanding telegraph network. His acquired telegraphic skills allowed Edison to earn a living, and to tinker, which is what he did best. He moved around a lot, to Kentucky, New York City, and New Jersey, being fired quite regularly, as his experimenting got in the way of his job. But by 1868, he had his first patent, for an automatic vote recorder, for the use of such institutions as Congress (second image). He learned a valuable lesson – before you invent something, make sure there is a market. No one, it turned out, wanted an automatic vote recorder. “Ayes” and “Nays worked just fine for most legislators.

I am guessing, and perhaps some poll will back me up, that “Thomas Edison” is the most frequent answer to the question on the street: “Who was the greatest inventor of all time?” I would venture that “Leonardo da Vinci” is the second most common response, but if we change our question, and ask “who was the greatest inventor and innovator?”, and explain that innovation involves implementing an invention, then Edison is clearly in a class by himself, as Leonardo put hardly any of his ideas into practice, while Edison had nearly 1100 US patents in his name.

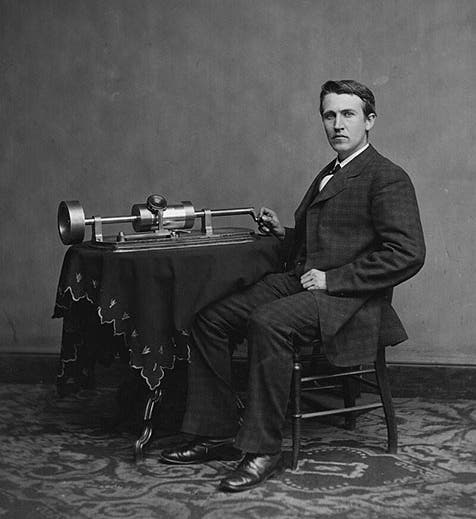

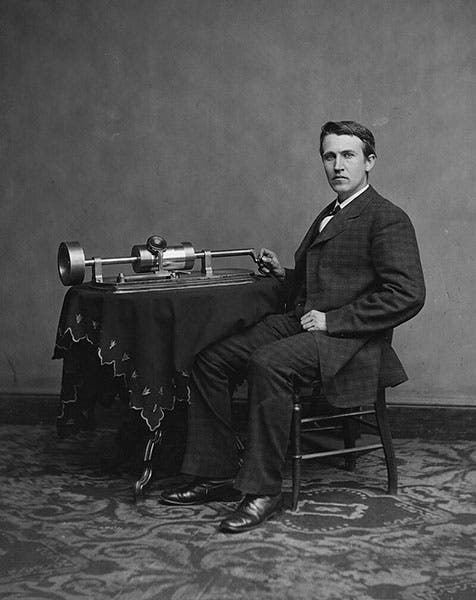

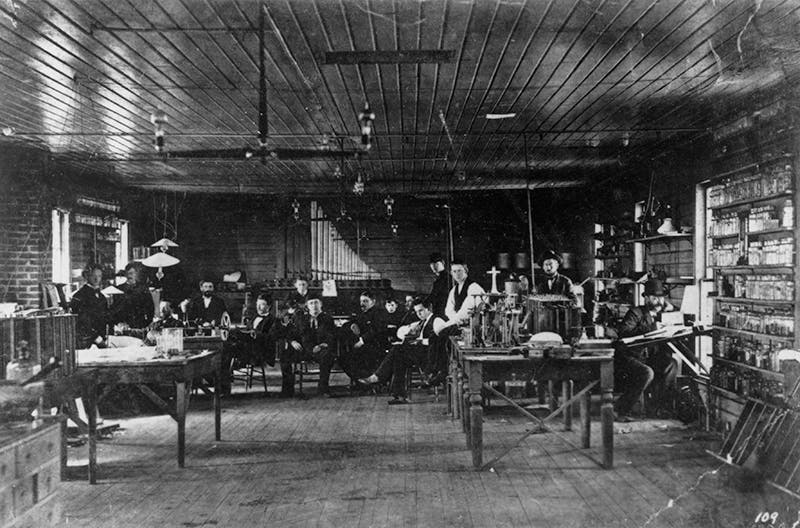

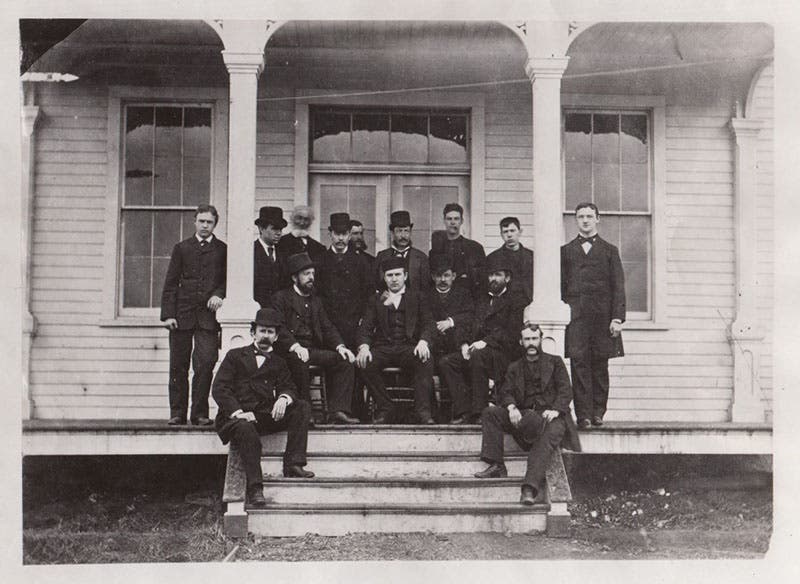

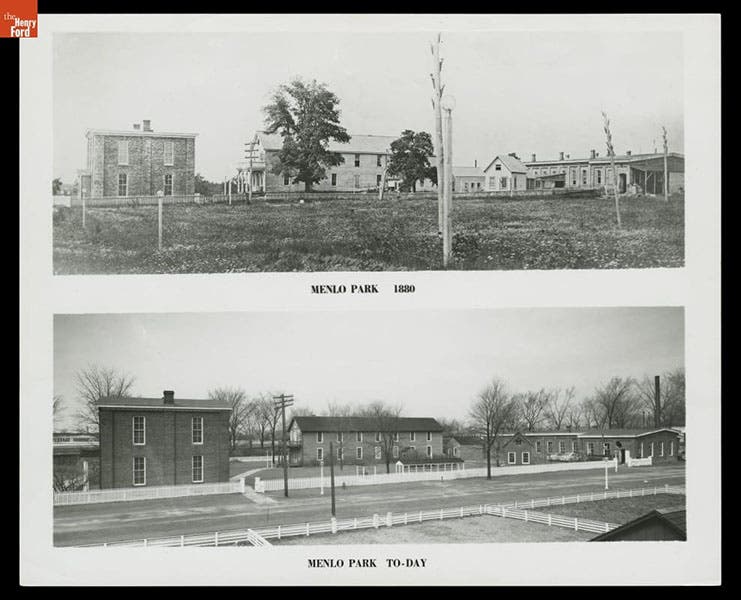

While most people imagine that Edison’s greatest invention was the light bulb, the fact is that dozens of people made light bulbs before Edison – he just made them last longer. His greatest invention was rather the invention laboratory, or invention factory, as it is often called. He built his laboratory at Menlo Park, New Jersey, in 1876, and staffed it with model-builders, machinists, glass-blowers, electricians, and other technical workers, and included storerooms that had everything right at hand – every kind of screw ever made, every size of wire and thread and metal stock available – so that ideas never had to wait. It was an amazing place; there really had never been anything like it (third and fourth images). And it was entirely independent of everyone except Edison. There was no university to answer to, or corporate board, or municipality. It was the first independent invention laboratory anywhere. The phonograph of 1877, the most unexpected invention of the entire century, sprang out of the Menlo Park environment (first image).

The historian of technology Thomas Hughes, in his book, American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm (1989) identified a period in American history that he called the era of the independent inventor, 1876-1925. It began with Edison and his exact contemporary, Alexander Graham Bell, who was also not associated with any institution when he patented his telephone in 1876. Hughes’ list of about a dozen independent inventors included Wilbur and Orville Wright, Nikola Tesla, Elmer Sperry, Lee de Forest, and Edwin Armstrong, all of who have been Scientists of the Day. Hiram Maxim, Elihu Thomson, and Reginald Fessenden round out the list, and we will get to all three of them when we can. And for Hughes, the era began with Menlo Park, because it changed the entire enterprise of invention.

Edison moved on from Menlo Park in 1886, to New York City, to set up his electrical stations for his proposed power network, and then he established later labs in other places, such as West Orange, New Jersey. Menlo Park, abandoned, went to seed, until Henry Ford, a great admirer of Edison, decided in 1929 to recreate the entirety of Menlo Park Laboratory at the Greenfield Village Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. His workmen gathered what original pieces they could, and reconstructed the rest. It is not exactly faithful – everything in Dearborn is a little bigger than it was in Menlo Park – but it is certainly impressive, and a suitable monument to the age of the independent inventor (fifth and sixth images).

There is a lot more to be said about Edison – about the light-bulb controversy; about his involvement in the “current wars” of the late 1880s and early 1890s, as the first power grids were being established by General Electric and Westinghouse; and about Edison’s role in the development of motion pictures. So we probably have at least two more Edison posts in our future.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.