Scientist of the Day - Theodore Richards

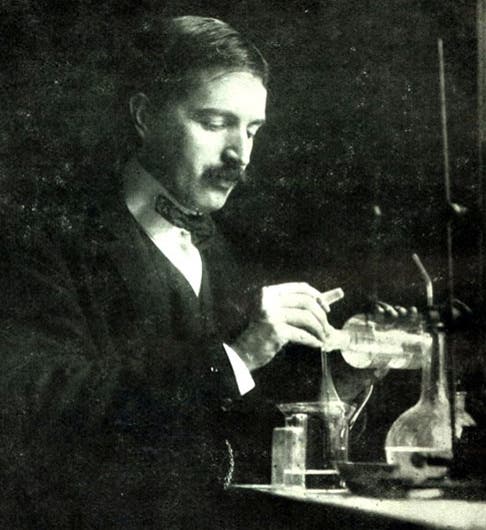

Theodore William Richards, an American chemist, was born Jan. 31, 1868. Richards taught and ran a lab at Harvard, and he became an expert at developing techniques for determining the atomic weights of elements with an unprecedented accuracy. Atomic weight (which we now call relative atomic mass) is the weight of all the particles in the nucleus of an atom, protons and neutrons plus binding energy, given as a multiple of a defined unit, which is now one-twelfth the mass of a carbon-12 atom. The unit of atomic weight is approximately the weight of a hydrogen atom, but not exactly.

Richards started off while a student in Germany trying to redetermine the atomic weights of oxygen and hydrogen, finding that the accepted figures were in error. At the time (1888), the oxygen atom was the standard, being defined as 16, and Richards found the atomic weight of hydrogen to be 1.0082. He moved on to copper, then barium and strontium, and other elements.

The basic technique, for the metals he was examining, was to work with the oxide, such as copper oxide, and to actually weigh the samples, with and without oxygen; knowing the proportion of copper to oxygen in the compound, it should be easy enough to find the ratio of the atomic weight of copper to oxygen. The problem in determining atomic weight is that the sample being measured may be contaminated, and it may contain different isotopes of the element in question. Different Isotopes by definition have different atomic weights, and the presence of isotopes had to be taken into account.

The principal contaminant that introduced error into atomic mass measurements was water, which Richards was the first to realize. Most compounds easily take up water, and it is very difficult to keep water out of the samples. Richards found ways to do this. By 1910, he had determined the atomic weight of 20 elements, each one an improvement on previous measurements. In 1903, for example, he measured the atomic weight of uranium to be 238.4; the previous value was 240.2. For some of his elements – the ones without isotopes – his measurements were accurate to one-thousandth of one percent, which is astounding.

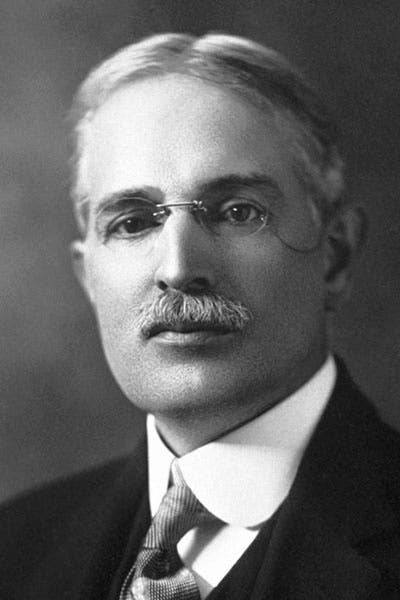

Richards was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 1914, becoming the first American to win the award (he actually received the award in 1915, for a reason I do not understand). He attracted students from all over to his lab at Harvard, one of them being James Bryant Conant, about whom we wrote a post in 2015, and who later married Richards' daughter. So Richards seems to have been a paragon of scientific success. And he was, for a while.

But I confess, I always feel bad for scientists like Richards, whose forte is pain-staking precision, and who are always trying to add an extra digit to the right of the decimal point. Because they must know that someday all those calculations are going to be surpassed. For Richards, that happened with the development of mass spectroscopy in the 1930s, by which, using the non-chemical method of accelerating atoms though a magnetic field and measuring the curvature of their paths, one could determine atomic weights with much better accuracy, so that very few of Richards’ atomic weights are valid today. When I think of Richards, I can't help but think of William Shanks, who spent 15 years calculating pi to 707 decimal places by hand, finishing in 1873. In 1944, pi calculator D. F. Ferguson not only did the same thing in a few weeks on a desk calculator, but showed that Shanks had made a mistake at place 527, and everything after that was wrong. Poor Shanks! But at least his accomplishment stood for 70 years. The laborious calculations of Richards were valid for not much more than 30 years. It is never good to die prematurely, but by passing away in 1928, at age 60, Richards was spared the painful experience of seeing his life work slowly rendered obsolete.

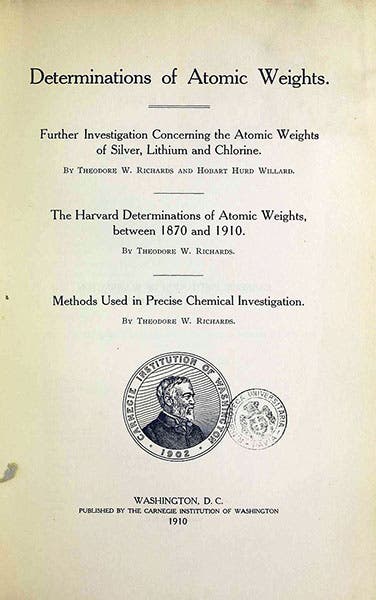

Most of Richards’ results were published in chemical journals, nearly all of which we have in our serials collection. But his principal monograph, Determination of Atomic Weights (third image), published by the Carnegie Institution of Washington in 1910, is not held by us, which is very odd. So to write this piece, I had to rely on the excellent account provided by his son-in-law, James Bryant Conant, who wrote the biographical memoir for the National Academy of Sciences.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.