Scientist of the Day - The Lumière Brothers

The Lumière brothers, Auguste and Louis, were a pair of pioneering French filmmakers and inventors. Auguste was born Oct. 19, 1862, and Louis almost two years later, on Oct. 5, 1864. They were raised in Lyons, where their father ran a photographic portrait studio, so both boys grew up with the latest developments in photography close at hand.

Auguste happened to see in Paris a demonstration of Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope, a kind of peephole motion picture. He wondered if it might be possible to develop a cinematic system that was not quite so massive, and which could project images on a screen for all to see, instead of requiring one-at-a-time viewing. By 1895, they had developed what they called a Cinématographe, which was an incredibly ingenious device. It was an easily portable wooden box that was at once a motion picture camera, a compact developing room, and a projector. It recorded 16 images per second on a 56-foot-long strip of 35 mm celluloid, driven by a hand crank, with sprocket holes in the film to advance the strip. The resulting film was developed right in the box. By setting up a magic lantern behind the box, the developed film could be cranked again and projected onto a screen. The strip of film produced a "movie" that was about 50 seconds long. Their Cinématographe was patented in February of 1895 (first image).

On this day, Mar. 22, 1895, the Lumière brothers showed one of their films to members of a society of industrialists in Paris. It was the first projection of any film for an audience anywhere, and is considered a historic event in the history of cinema. The film shown was La Sortie de l'usine Lumière à Lyon, usually translated as Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory. It will not overwhelm you with its plot, since it simply records workers, mostly women, rapidly exiting the Lumière factory, streaming out right and left, with the occasional dog or bicycle or angry man thrown in for some variety. The film survives in three versions, one of which has a horse-drawn carriage emerging at the very end, another with a two-horse carriage, and a third (thought to be the first one made) with no carriage and no horses. You can see all three versions, back to back, 110 seconds worth, at this link.

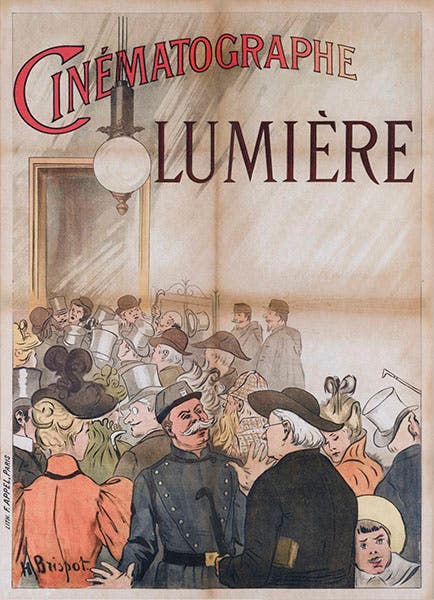

In December of that same year, La Sortie and nine other filmstrips were shown to a paying public in Paris. For many historians, this marks the true birth of cinema. The Lumière brothers even seem to have invented that staple of modern cinema, the movie poster (third image). There are other candidates for the first public screening of a film, one in New York; I don't know enough to evaluate rival claims for who was truly “the first.” But it seems that, with the other claimants, we have no idea what was shown and how the film was made. With the Lumière brothers, we can see exactly what they produced and projected. If you want to see the ten short films that enthralled a paying audience on Dec. 28, 1895, here they are, back to back (the piano accompaniment is a later addition, but OK by me).

The Lumière Cinématographe was a great success; it was much more popular with the public than the Kinetoscope. Many Cinématographes were produced, and the brothers traveled all around the world giving demonstrations. Eventually, however, they lost interest, seeing cinema as just a novelty, and they turned to developing color photography. Their “Autochrome Lumière” was apparently quite successful, but I know little about it, and we will not attempt to tell that story here.

There is a Musée Lumière at the Institut Lumière in Lyons, built on the site of the old Lumière factory, where you can see original Cinématographes, some set up in projector mode (fourth image). There is also one on exhibit in the Science Museum in London (first image). There are almost certainly some on display in the United States, at the Smithsonian Institution or at other museums of science and industry (or cinema), but I have not yet located any American specimens. If you know of any, please feel free to let me know.

If you are interested in how the Lumière Cinématographe was able to perform three different functions, this four-minute animation without narrative or sound will shed some light on the process.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.