Scientist of the Day - Thales of Miletus

We are coming up on the eighth anniversary of the Scientist of the Day blog. Of the 2000 or so posts published so far, not one has featured a classical Greek natural philosopher or mathematician. The reason is not hard to find – in an enterprise structured around dates of birth, death, or significant events, it is difficult to find a place for those with no dates attached to them at all. But as we have now run through every day of the year at least 6 times (dates on weekends don’t count), we are starting to run out of suitable candidates on certain calendar days. So I have decided that if there are no more worthy scientists to write about on a given day, I will choose someone without an attributed date who IS worthy of celebration. We begin to enter those expanded horizons today with a post on the first known Greek natural philosopher, and we will continue to profile other ancient natural philosophers in the coming years as the occasion allows.

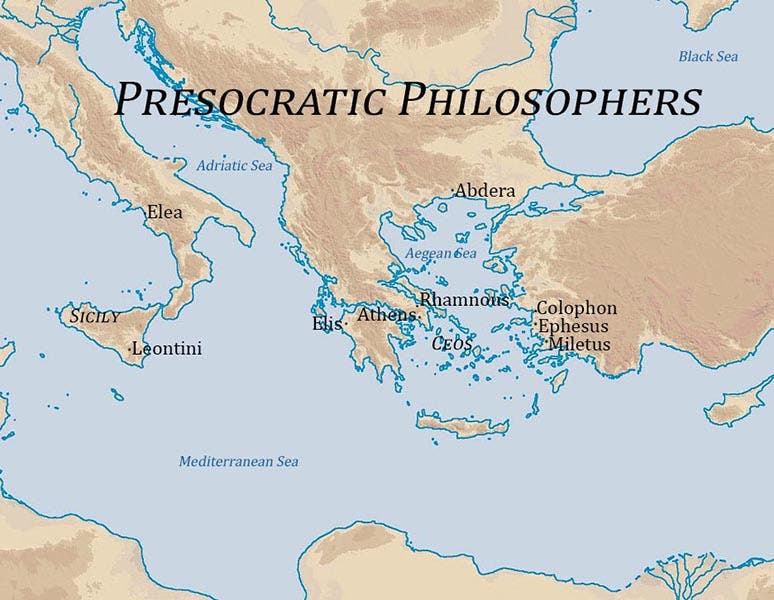

Thales of Miletus, an Ionian natural philosopher, lived in the first half of the sixth century B.C.E. The only semi-firm date we have for Thales is a solar eclipse of May 27, 585 B.C.E., which he is supposed to have predicted. If he was in his prime at the time of the eclipse, that would mean that he was born about 620 B.C.E. and died anytime between 575 and 550 B.C.E. Miletus was a port city in southern Ionia, one of many cities populated by Greeks that sat on the western coast of Asia minor in an area known as Ionia. Thales is thus referred to as a Greek, an Ionian, a Milesian (citizen of Miletus), and because he lived before Socrates, a Pre-Socratic (see map, second image).

Thales is known by name to every student who takes an introductory course in Western philosophy, because he was, so it is said, the first Greek philosopher, who turned away from the mythopoeic world view of the Babylonians and began to ask such questions as: what is the basic stuff that comprises the world. He thought that basic substance is water, but the answer is not as important as is the unprecedented suggestion that one could explain the makeup of the world without recourse to deities or supernatural forces, which provided most of the explanatory detail in Babylonian speculations on the origin of the world.

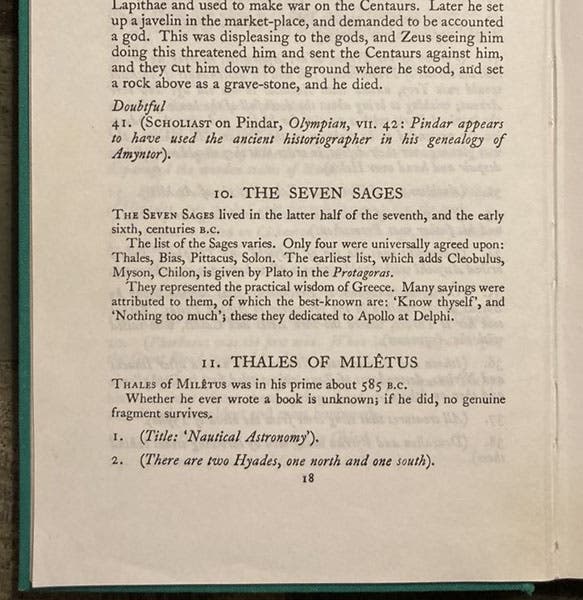

One fascinating thing about Thales, at least to me, is that he has achieved prominence in the history of western philosophy, in spite of the fact that we know so little about him. When I used to introduce Thales and the Ionians to my classes in the history of science, back during my teaching days, I would bring along a copy of Kathleen Freeman's Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic philosophers (1971). This book contains translations of the complete writings of every Greek philosopher who lived before Socrates, i.e., before about 400 B.C.E, so a two-hundred-year period. There are 90 individuals represented, and yet the book is quite thin, just over 160 pages long. I would open it to the page on Thales and show them the three-line entry: “Thales of Miletus was in his prime about 585 B.C. Whether he ever wrote a book is unknown; if he did, no fragment survives” (third image).

The complete works of Thales, in Kathleen Freeman, Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers, Harvard University Press, 1971 (author’s collection)

Despite the absence of any original works or even fragments by Thales, there are many stories told about him. It is said that one day, while walking along, looking at the heavens, he fell into a well, the moral being: don’t forget about daily life when your mind wanders among the stars. It is also related that one year, Thales, realizing there was going to be a bumper olive crop, secured the rights to all the olive-presses in Miletus, thus showing that while philosophers may be strange, they are also clever, and could make lots of money, if they wanted to. Where do these stories come from, if no documents survive? They are a product of what we call the doxographic tradition, the writings of ancient authors who presumably had access to documents that no longer survive. The well story comes from Plato, and the olive-press story from Aristotle, both writing about 2 centuries after Thales died. There is nothing wrong with mining the doxographic literature for stories like these, so long as we continually remind ourselves that they are just stories, and may be devoid of any historical truth.

One other narrative attributed to Thales will bring us back to his natural philosophy. Thales is said to have wondered about the causes of earthquakes, and speculated that the Earth floats on water, and occasionally is rocked by waves in the primordial sea, causing the Earth to shake. The remarkable feature of this speculation is that there is no mention of supernatural forces, or Gods waging war, or anything except matter affecting other matter. What prompted Thales to opt only for natural explanations is one of the great unanswered questions of Pre-Socratic studies, so mysterious that it was once called the “Greek miracle,” an ironic term if ever there was one, since the essence of Pre-Socratic explanation was the foregoing of miracles.

The other innovation of Ionian thought was philosophical discussion and criticism. Thales had colleagues, and they talked about and debated such questions as the nature of original matter, and the arrangement of the cosmos. There is no reason to think that the people who wrote down Babylonian and Egyptian stories about the origins of things did not discuss and disagree. But in all previous cosmogonic narratives, there was no need for consistency – three entirely different stories could account for the passage of the Sun around the Earth, and if they contradicted each other, it did not matter. With the Milesian school, as it developed, consistency DID matter, for only one explanation could be true. That was a brand-new standard for Western philosophy. We will see how this emerged when we discuss, on some future occasions, the other two Milesian philosophers, Anaximenes and Anaximander.

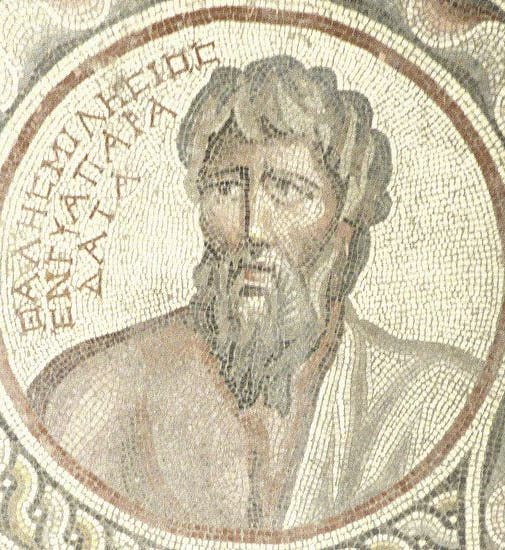

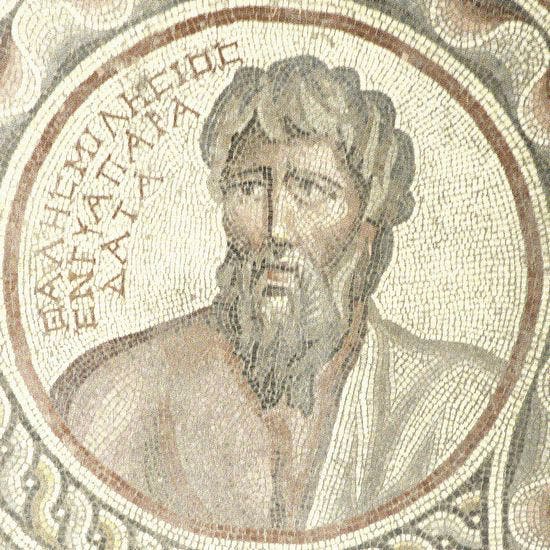

It should not be surprising that there are no surviving contemporary portraits or busts of Thales. In fact, there are only two depictions of Thales in the first thousand years after his birth. There is nothing wrong with using them, provided one understands that they are not portraits in the conventional sense. A beautiful mosaic was installed, perhaps in a villa, in the 2nd or 3rd centuries C.E, near Baalbek in modern Lebanon, that shows the Seven Sages of Antiquity, of which Thales was one. You can see the complete mosaic at this link. We show here, as our first image, a detail of the mosaic portrait of Thales. He is identified by the first two words of the Greek inscription, Thales Milesios. It is as good a way as any to picture the father of Western natural philosophy.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.