Scientist of the Day - STS 61

The Space Shuttle Endeavour was launched Dec. 2, 1993, on a mission known as STS-61. This may have been the most important of the 135 shuttle missions flown, because it saved the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and rescued NASA from a public relations disaster.

The HST had been launched in 1990 with high hopes for this new eye in the sky, but it quickly became clear (perhaps not the right word) that something was seriously wrong with the telescope, since images were out of focus. An extensive investigation revealed that the main mirror, a 94-inch disc of glass, had been ground incorrectly, due to a flawed measuring device, and was exhibiting “spherical aberration,” meaning that light rays reflected from the edge of the mirror were being brought to a different focus than rays from the central region.

The crew of STS-61 in space; Richard Covey, mission commander, is at center; the woman, Kathryn Thornton, was one of the mission specialists who installed the corrective package COSTAR and the new camera WFPC2. The solar panels of the Hubble telescope are visible through the windows (appel.nasa.gov)

The press had a field day; Newsweek ran a front-page story on July 9, 1990, with the headline "Star Crossed: NASA's $1.5 Billion Blunder." Congressmen were outraged and did what they always do when they are outraged – held committee meetings. The President (George H.W. Bush) simply said: Fix it, or else. That turned out to be the right mandate.

Fortunately, the HST had been designed so that everything was replaceable, except the main mirror. All you had to do was figure out how to fix the main mirror without touching it, design new instrument packages, and somehow remove the old ones and install the new ones, all while hovering in space some 330 miles above Earth.

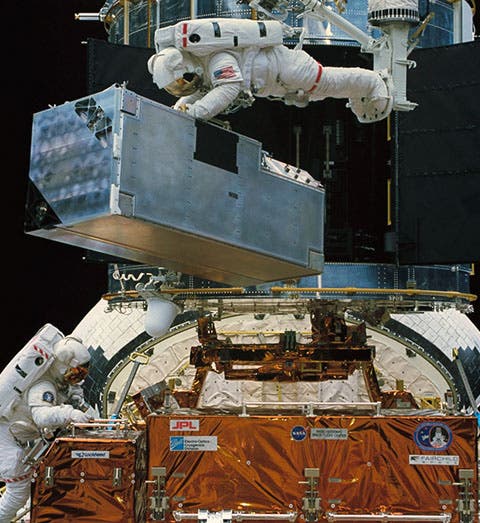

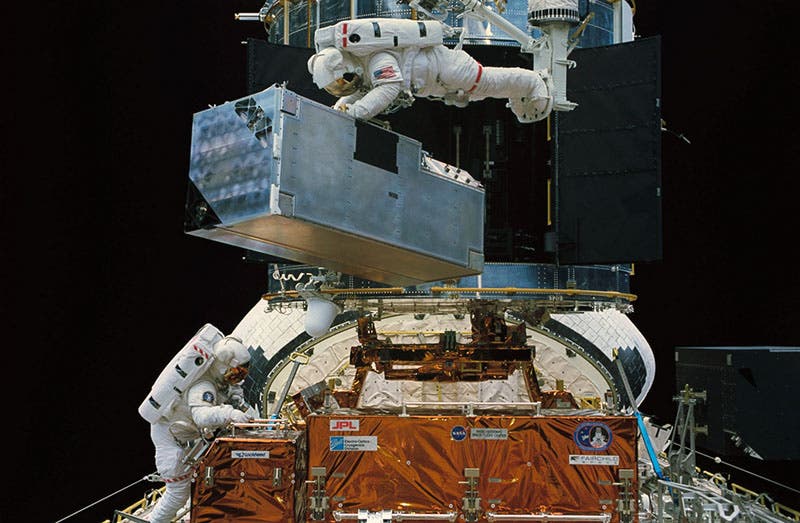

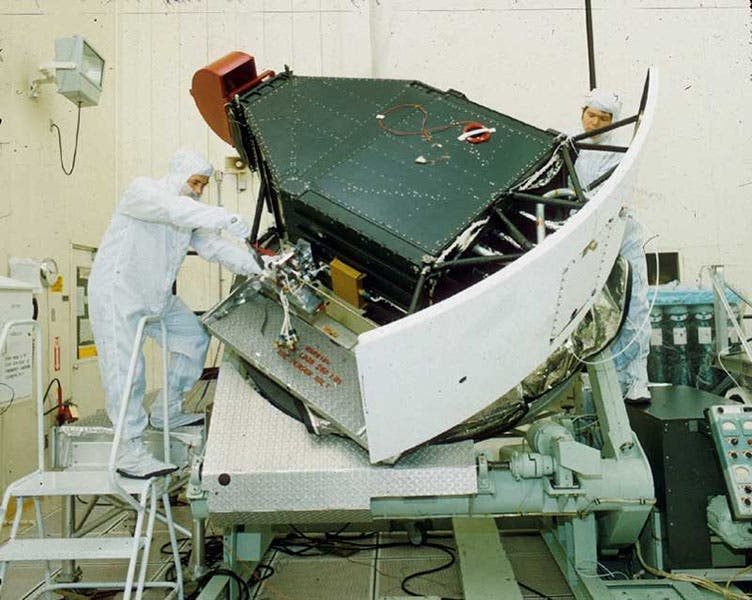

So a "corrective optics" package was designed. Part of it was something called COSTAR, a refrigerator-sized instrument that was, in effect, a set of eyeglasses for Hubble, correcting the field of view being provided to the many instruments on the HST. The second was a new Wide Field and Planetary Camera, WFPC2 (fourth image), replacing WFPC1, which would provide the images that later would later leave us all in awe, including the “Pillars of Creation and the “Hubble Deep Field”, both of which you can see at our post on the Hubble Space Telescope. WFPC2 had its own corrective optics package and incorporated many other improvements.

Two top crews were selected and trained to repair the HST in space. The mission was very complicated, involving 5 long space walks in all, with the two crews alternating to prevent fatigue. COSTAR was installed on the second spacewalk; one of the mission specialists performing the installation was a woman, Kathryn Thornton, on her third shuttle mission (first image). Jackson’s team of two was also responsible for installing the new wide-field camera on the fourth spacewalk. The other crew replaced the solar panels, which had been damaged when the HST was originally deployed.

The 11-day mission of STS-61 was a complete success. HST now performed flawlessly and would provide us with stunning photographs for decades to come. One of the most effective was the first, a photograph of a galaxy, M100. HST had recorded an image before the optics were corrected, which was noticeably out of focus; the new image allowed everyone to evaluate the fix, and the evidence was striking (sixth image). NASA ‘s reputation was almost instantly repaired. The Space Shuttle program gained new respect and admiration. Most importantly, HST now had a new lease on life. It is hard to imagine what the history of space exploration would have been like without ti.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.