Scientist of the Day - Stamford Raffles

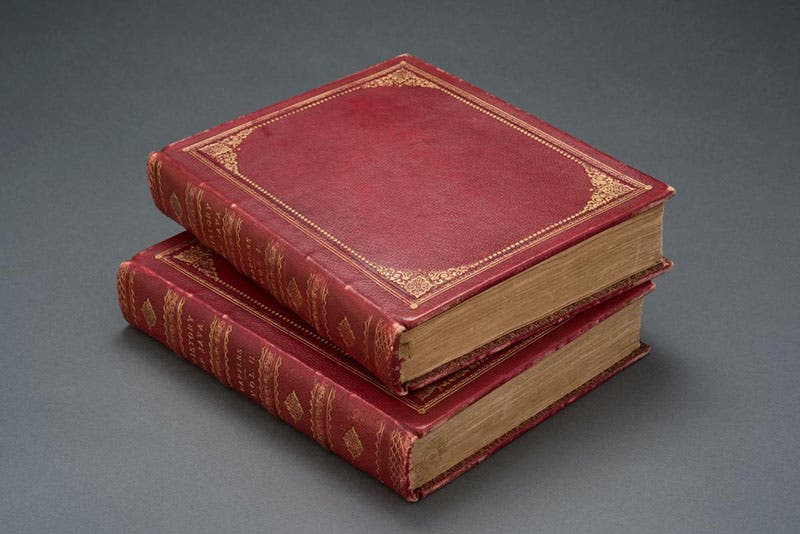

Thomas Stamford Raffles, an English official in the British East India Company, was born July 5 or 6, 1781. Raffles played an important role in the taking of Java from the Dutch during the Napoleonic Wars, and he presided there as Lieutenant Governor for 4 years before England agreed to give Java back to the Dutch in 1815. Stamford (as he preferred to be called) was not a scientist, but he had a deep interest in natural history, and so while he was in Java, he supported several naturalists, including Thomas Horsfield, who gathered specimens for a natural history of Java. Raffles himself preferred to write a cultural and political history of the country he ruled, which was published as The History of Java in 1817. We do not have this set in the Library, and I am not sure we should, since its scientific content is minimal, although it has 10 lovely aquatint plates of peoples and places. We show you the closed two-volume set from the National Library of Singapore (second image). Four years later, Horsfield began issuing fascicles for his Zoological Researches in Java, and the Neighboring Islands (completed in 1824), and that is the book on Java we should have, but we don’t. We have been looking for years, but it is rare, and when it does come up, very expensive.

Raffles is best known for founding the city of Singapore in 1819. This was during his second tenure in Indonesia, when England was looking for another place to establish a presence in the Dutch-controlled Indies, and Raffles helped chose this favorably situated island on the Malay Peninsula that the Dutch had ignored. In fact, of the three people who played a role in founding Singapore, Raffles was the last and the least active, and he actually spent very little time there – some eight months in all. But he was apparently a very likeable fellow, and he successfully corrected some of the socially unjust practices set up by his co-founders. Raffles was very much opposed to slavery, and he respected the Malay people and treated them well. As a result, he is the one commemorated as the founder of Singapore, with statues and plaques scattered throughout the city, and now, even a hotel named after him.

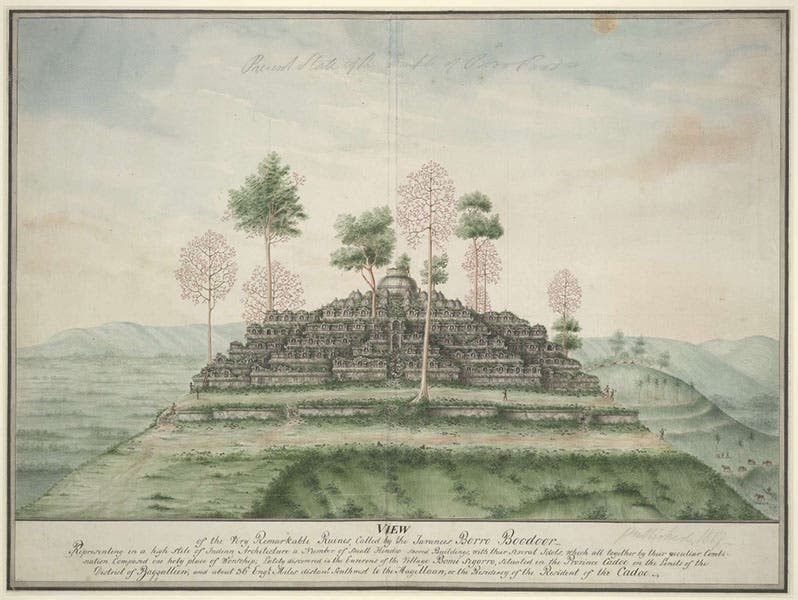

It is not so well-known that Raffles was responsible for the rediscovery of Borobudur, the great Buddhist temple that was built in Java in the 9th century and then abandoned to the jungle after most of the country converted to Islam in the 14th century. Supposedly Raffles himself never visited the ruins, but when he heard rumors of its existence, he sent a party to clear the site, and it has stayed cleared ever since. There is a watercolor of Borobudur from the Raffles collection in the British Museum; the description does not say who the artist might have been, but apparently it was not Raffles himself (third image). Still, as apparently the first Western representation of what is now the most popular tourist attraction in Indonesia and the largest Buddhist temple in the world, that makes the drawing quite special. Borobudur became a World Heritage Site in 1991. Here is a modern photograph for comparison with the Raffles sketch.

Raffles did not collect plants, but he has one named after him, and it is a wonder: Rafflesia (fourth and fifth images). This is a parasitic Indonesian plant that lives mostly inside various tropical vines. The only outwardly visible part is the bloom, which makes up for its invisible body parts by being up to a full meter across, making it the world's largest flower. The second photo includes some local children to provide a sense of scale. Raffles must have been pleased at the grandeur of his plant. It was named in 1821, by Robert Brown, while Raffles was still alive, so he knew about it. The plant was discovered in 1818 by a guide working for Joseph Arnold, who worked for Raffles, hence the full name: Rafflesia arnoldii. However, the flower has a strong odor of rotten meat and is usually crawling with carrion beetles and flies. This would seem to take some of the bloom off the honor of being a namesake.

Raffles was very ill when he finally returned to England in 1824, although he survived long enough to help found the Zoological Society of London and the London Zoo. But he died on or just short of his birthday in 1826, age 44 or 45. He was buried in St Mary Churchyard in Hendon in greater London, but because of his anti-slavery stance, he was refused burial within the church, whose vicar was a supporter of slavery. Eventually, the church expanded to include Raffles’ plot, which is now inside the building and is commemorated by a small plaque and a memorial stone, both of which you can see at findagrave.com.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.