Scientist of the Day - Sputnik I

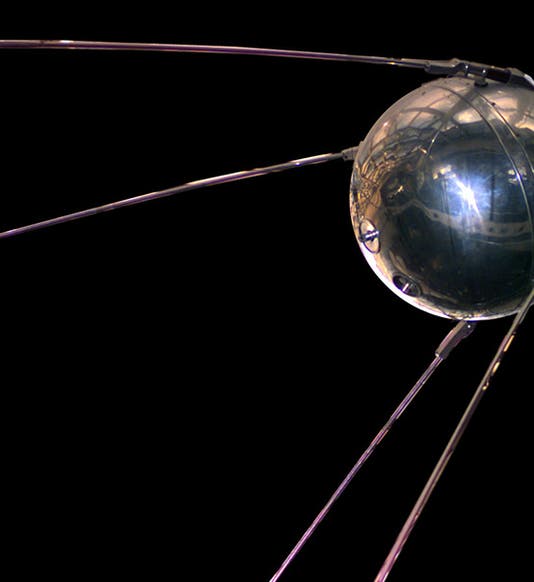

Sputnik I, the world's first artificial satellite, was launched into orbit by the Soviet Union on Oct. 4., 1957. A number of epochal spacecraft have been launched since, including Apollo 11, Pioneer 10, Voyager 1, and Viking 1, but it is difficult not to award Sputnik I the honor of being the most significant spacecraft of all. Sputnik wasn't much to look at – an aluminum alloy ball less than 2 feet in diameter, with four whip antennae sticking out that gave the impression that two large cockroaches were imprisoned within. Weighing 184 pounds, it was put into an elliptical orbit, its distance from earth varying between 130 and 580 miles. It took 96 minutes to complete one orbit.

Sputnik and its launch were engineered by Sergei Korolev, an aerospace designer who is hardly known in the West. In fact, before his untimely death in 1966, he was not known at all, since the Soviet Union took pains to keep his identify secret, fearful that some agent of the West would take him out. Korolev designed the rocket, the S-7, that launched Sputnik, and many succeeding Soviet spacecraft (second image). A stroke of genius was his decision to fill the shell of Sputnik with three batteries and a radio transmitter. As soon as Sputnik achieved orbit, it started beeping at 20 and 40 megahertz, and it beeped persistently until its batteries ran out 22 days later. 20 MHz was in the frequency range of Amateur Radio operators, so ham radio sets around the world were soon tracking Sputnik and, in the process, advertising the Soviet triumph. Moreover, any American could go out at night, just after sunset, and see a tiny dot of light moving slowly across the sky. It was probably the booster rocket that you saw, and not Sputnik itself, but it didn’t matter – it was up there, and it wasn’t ours. This one-minute YouTube video, which has some original footage of the assembly and launch of Sputnik, uses as a soundtrack the “beep-beep-beep” of the spacecraft.

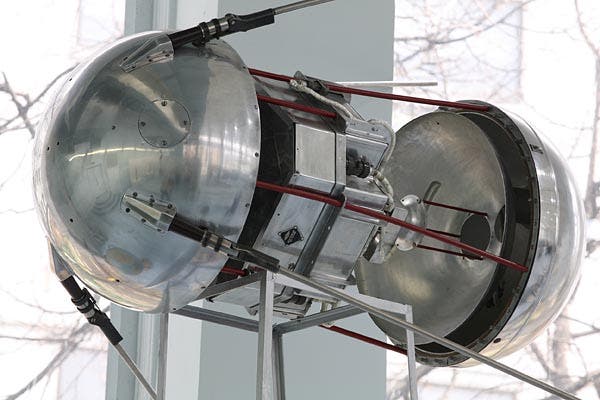

You cannot see the Sputnik that went into orbit – it burned up on Jan. 4, 1958, after 92 days in orbit. But several back-up Sputniks were made, and at least two of those are on display. One is in Moscow, in the Energia Museum, where the spacecraft is displayed in an exploded view, so you can see all the batteries and the transmitter inside (third and fourth images). Another original Sputnik is in the Cosmosphere in Hutchinson, Kansas (fifth image); its acquisition must have been quite a coup for the museum, since the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., has had to settle for a replica (first image). Both back-up satellites were flight-ready, meaning that were fully equipped with batteries and a transmitter. There is another Sputnik on display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle that is said to be original, but it has no innards.

The launch of Sputnik I marked the dawn of the Space Age, and also the beginning of the Space Race between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. The presumption up to Oct. 4, 1957, was that America would be the first into space. The success of Sputnik I was quite a shock, and it would take the U.S. five months to get their puny 31-lb Explorer I into orbit, and quite a few more years to actually catch up. But for all their progress, no American satellite could ever be first. That honor can never be taken away from Sputnik I.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.