Scientist of the Day - Smithson Tennant

Smithson Tennant, an English chemist and physician, was born Nov. 30, 1761. Tennant’s grandparents resided in Wensleydale, in North Yorkshire, and his parents about 60 miles south of there, in Selby. Through propitious marriages, enough wealth and land was pieced together so that young Tennant was to have no financial worries. He showed an early interest in chemistry (his grandfather was an apothecary), and he eventually found his way to Cambridge to study medicine, although it was the chemical side of medicine that appealed to him. When he finally became doctor of medicine in 1796, he decided that medical practice was not for him, so he moved to London and there set up shop, of sorts, with an old classmate, William Hyde Wollaston. The two entered into a partnership to make platinum boilers. To that end, they acquired a large 400-pound chunk of platinum ore, called platina, from Columbia in South America. While dissolving pieces of platina in aqua regia, they examined the black powder residue left behind, and each man made separate but equally significant discoveries. In 1803, Wollaston extracted, from the platinum ore residue, two new elements, palladium and rhodium. We wrote a post on Wollaston and his discoveries this past summer.

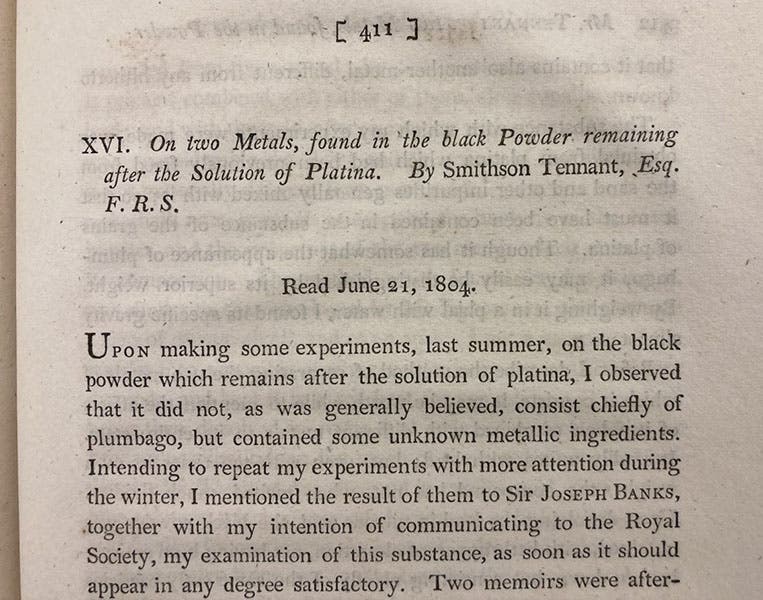

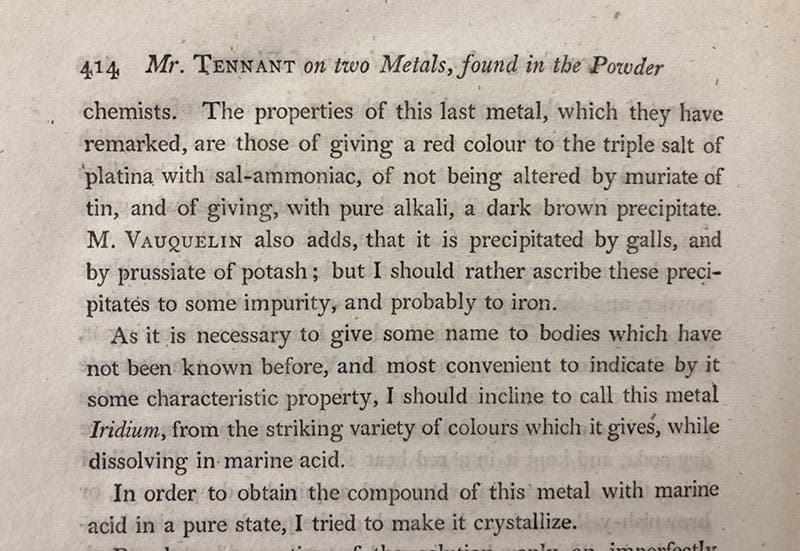

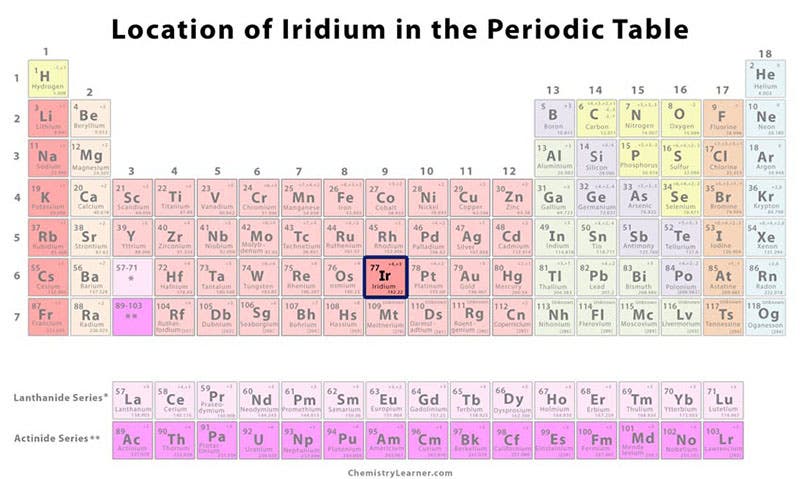

Not to be outdone in the new-element department, Tennant isolated two more elements from the same residue in the same year, which he called osmium and iridium. Like Wollaston, he announced his new elements in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society for 1804. We show here a detail of the first page of his article: “On two Metals, found in the black Powder remaining after the solution of Platina,” as well as the page where he named iridium (second and third images). All four of the new elements are part of what is called the platinum group, sharing the same chemical properties and occupying the same general region of the periodic table (fourth image). The periodic table did not exist when Tennant and Wollaston made their discoveries.

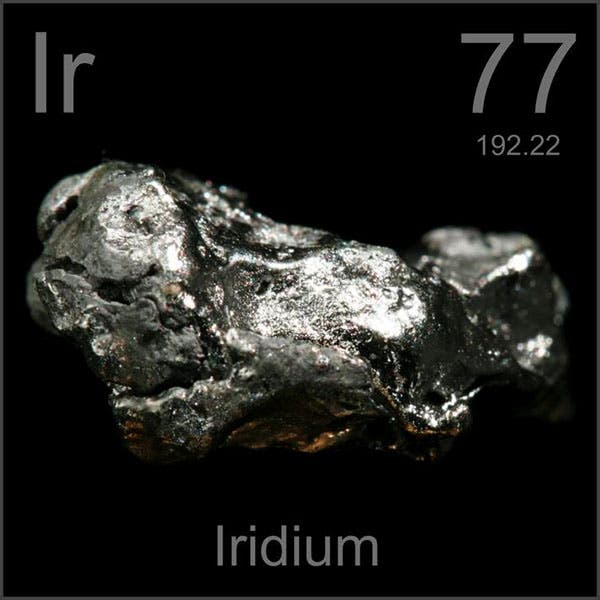

Osmium, one of Tennant's finds, is the densest of the naturally occurring elements, being twice as heavy as lead, which means a coffee cup full of the stuff would weigh about 10 pounds. Tennant's other new element, iridium, is the second densest element known. We see a sample below (fifth image). Iridium came to prominence in 1980, when an unusual amount of it was discovered in a layer of clay that was deposited at the end of the Cretaceous period, when the dinosaurs disappeared. Since iridium is rare on earth but abundant in meteorites, the "iridium anomaly" led to the proposal by Walter and Luis Alvarez that the Cretaceous extinction was caused by the impact of a large meteorite.

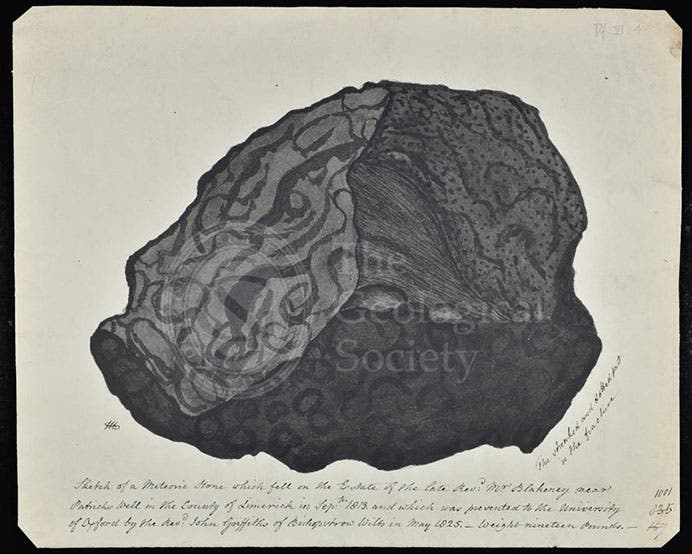

Tennant was also interested in meteorites, although not because they contain iridium. He just found them chemically intriguing, as did many of the early students of meteorites, such as Edward C. Howard. He determined the nickel content of the Cape of Good Hope meteorite, a chunk of which was acquired by James Sowerby, and he was one of the first to examine pieces of the Limerick meteorite, which fell in Ireland in 1813. Indeed, he took a piece of the Limerick meteorite to France with the expressed purpose of presenting it to fellow chemist Claude Berthollet. While there, Tennant rode a horse across a bridge that collapsed; the horse fell on top of him, and he was killed. He was 53 years old.

It is odd that there is no documented portrait of Tennant, although there are several presentable portraits of Wollaston. About all we have to remember Tennant by, other than his two platinum-group metals, is a blue plaque outside his birth house in Selby, a building that is now a pub (first image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.