Scientist of the Day - Sinclair Lewis

Sinclair Lewis, an American novelist, was born Feb. 7, 1885, in Sauk Centre, Minnesota. He attended Yale University and began writing novels in the 1910s. He had his first big success in 1920 with Main Street, and then followed with Babbitt (1922), Elmer Gantry (1927), and Dodsworth (1929). But it was the novel that was published in 1925 that attracts our attention here – Arrowsmith, the first American novel to have a research scientist as its hero, or at least as protagonist.

Around 1923, Lewis met Paul de Kruif, a microbiologist who was working at the Rockefeller Institute in New York. De Kruif had the notion that American medicine had been corrupted and that present-day doctors were more interested in getting rich than in serving the community, and that we need a return to the higher ideals of humanitarians like William Osler. He was no doubt influenced by the Flexner Report of 1910, in which Abraham Flexner, in a study written for the Carnegie Foundation, was critical of the current state of medical education in the United States and lamented the fact that many medical graduates had no awareness or understanding of basic scientific method (see our post on Flexner). Lewis decided to write a novel about a physician from the American Midwest with high medical ideals but who had to deal with the temptations of financial rewards and the conniving of the medical and pharmaceutical establishment.

Since Lewis had no first-hand experience of any of this, he asked de Kruif to collaborate with him on Arrowsmith, paying him 25% of the royalties (but not inserting his name on the title page). De Kruif provided not only inside knowledge on places like the Rockefeller Institute but also much of the plot line, and sketched out some of the major characters, such as Martin Arrowsmith and his mentor Max Gottlieb.

In the novel as published, Martin Arrowsmith comes up through the medical system, is steered in the right direction by Gottlieb, with his high ethical standards, works for a time in public health, but then his own moral standards slowly erode away, and he finally ends up with a well-paying job at a fictional Rockefeller. Then he discovers a bacteriophage (a virus that kills bacteria), and when a plague epidemic strikes a Caribbean island, he uses the phage, without proper medical testing protocol, to save the remaining population. He is lauded in the press, but privately Arrowsmith is distressed that he abandoned all the medical teachings of Gottlieb about proper scientific method just to become a hero. He is offered the directorship of the Institute, but he gives it all up, including his wife and son, to move to rural Vermont to pursue pure research, as he had been taught by Gottlieb.

The figure of Arrowsmith appears to have been fashioned after Felix d’Herelle, the actual co-discoverer of bacteriophages. We have yet to write an essay about d’Herelle, but he made an appearance in our post on Geog Eliava, an advocate of phage therapy, just last month. The character of Gottlieb was modelled on Jacques Loeb, a bacteriologist at the Rockefeller Institute whom de Kruif knew and greatly admired. We have published a post on Loeb.

Arrowsmith sold very well, like all of Lewis’s novels of the 1920s, but unlike most novels about physicians. Lewis received the Pulitzer Prize for Arrowsmith, but he declined the award, for reasons he did not make entirely clear in his declination statement, but which others have interpreted as a reaction to the fact that he did not get a Pulitzer Prize for Main Street five years earlier, and he was still mad. Lewis did not decline the Nobel Prize four years later, which carries with it a lot more money. After the success of Arrowsmith, Paul de Kruif went off on his own and published The Microbe Hunters in 1926, which became one of the best-selling medical books of the next 30 years and inspired a generation of physicians, even though it is mushily written and historically unsound. But it is enthusiastic and full of heroes, even if many of them are cardboard.

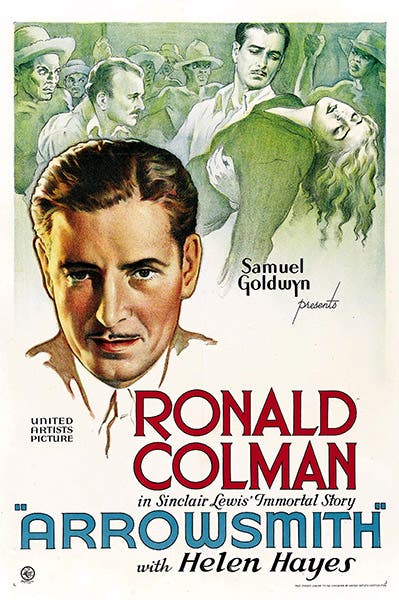

A movie was made from Lewis’s novel in 1931, with the same title, Arrowsmith. It featured Ronald Colman as Arrowsmith and Albert Anson as Gottlieb. I have not seen the film (third image).

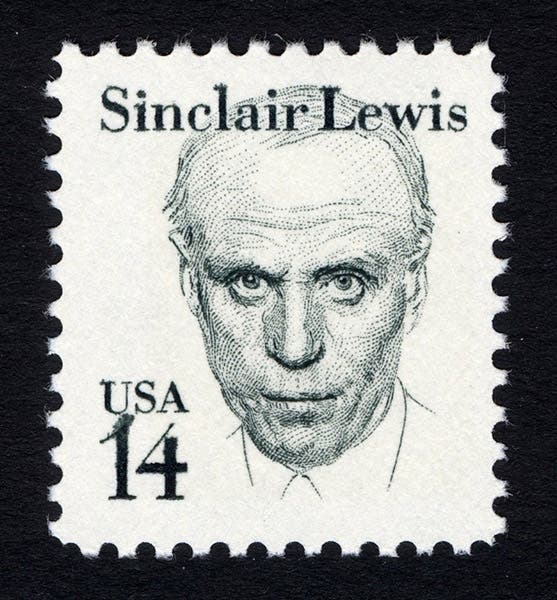

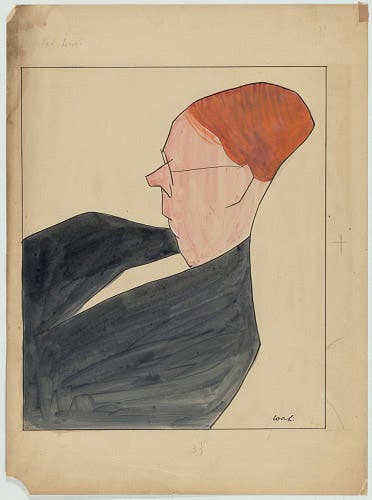

There are at least a dozen portraits of Lewis in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington. I prefer to show you a postage stamp, issued in 1985, with Lewis’s portrait (second image). You can see the original drawing, from which the stamp was made, in the NPG. Since we have room, I also include a caricature of Lewis, drawn by William Auerbach-Levy around 1930, that appeals to me (fourth image).

In 1935, Lewis published a novel, It Can't Happen Here, about a fascist who becomes president of the United States. It has had a resurgence of popularity since 2016, I have no idea why.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.