Scientist of the Day - Sandford Fleming

Sandford Fleming, a Scottish-born Canadian engineer, was born Jan. 7, 1827. Nearly every brief biographical notice of Fleming (including this one, apparently) notes three facts about him: he designed Canada's first postage stamp (the 1851 “Three-penny beaver"); he was a major force in the construction of the first intercontinental railroad in Canada, the Canadian Pacific Railway; and he invented the idea of time zones. We are going to discuss the third accomplishment, although we could not resist illustrating the first, for an opener (first image).

Time-keeping was a problem for railroad managers in the 1870s, as each city and town had its own local time that often bore no easy relationship to time in other cities and towns, and this made it nearly impossible to construct usable railway schedules. Fleming proposed as early as 1879 that the problem could be solved by the adoption of standard time zones, preferably 24 of them around the world, each an hour apart. He did not get much support in Canada, but he did across the border in the United States, where the American Society of Civil Engineers was made up almost entirely of railway men, who keenly felt the need for standard time zones. They appointed the Canadian Fleming as the Chairman of a Special Committee on Standard Time. We have several of the Committee's Annual Reports in the Library, including one for 1884, when the Society held a convention in Buffalo (second image). The 1884 report, signed by Fleming, strongly urged that a system of 24 time zones be adopted.

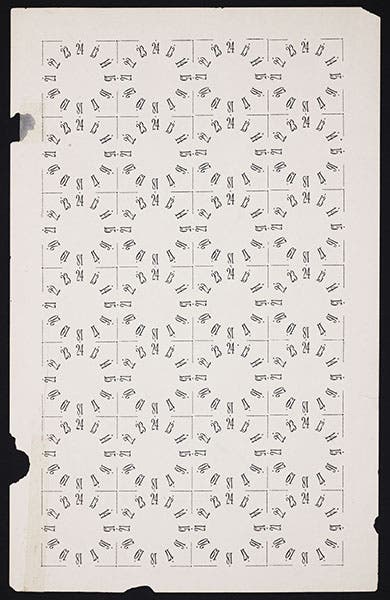

Since that would require a 24-hour clock (or, for the railway men, pocket watches), the report thoughtfully included an insert with tiny printed labels, with the hours 13-24 in a circle, that could be pasted inside the hours 1-12 already on the watch face (third image).

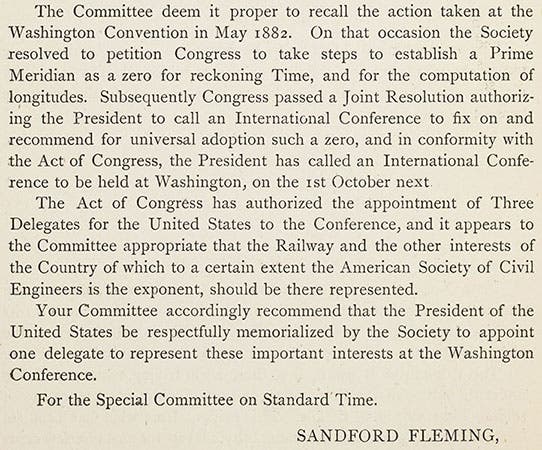

Later that year, in Oct. 1884, an International Meridian Congress was held in Washington, D.C., during which the Greenwich meridian was chosen as the Prime Meridian, and Greenwich Mean Time was established as standard time (Fleming had called attention to the upcoming Congress in his 1884 Annual Report, fourth image).

Fleming attended the Meridian Congress, representing the Dominion of Canada for Great Britain. It is often said that the Congress adopted Fleming's proposal for time zones based on a 24-hour clock, but they did not, thinking it inappropriate for an international commission to decide how local communities kept time. It was such a sensible idea, however, that, within about 40 years, most countries had established time zones very much like those recommended by Fleming.

We also have a copy of the Protocols of the Proceedings of the International Meridian Congress in the Library, and we showed some images of it some years ago, when we celebrated the anniversary of the establishment of the Prime Meridian at Greenwich.

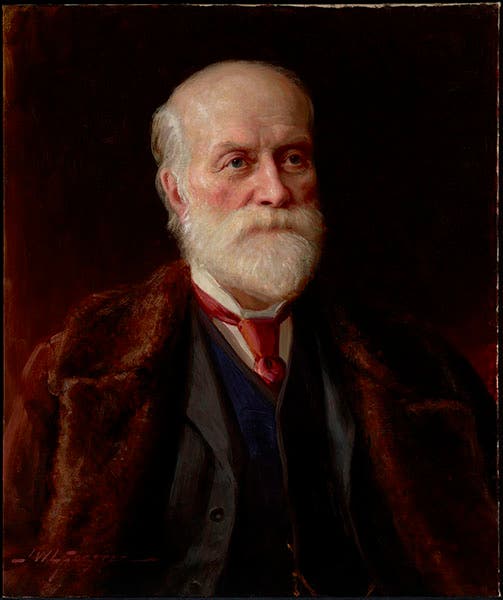

The portrait of Fleming, painted in 1892, is in the Library and Archives of Canada in Ottawa (fifth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.