Scientist of the Day - Samuel Wendell Williston

Samuel Wendell Williston, an American entomologist, paleontologist, and physician, was born July 10, 1852, in Boston. He moved with his parents to Manhattan, Kansas, when he was young, and he was raised there, attending Kansas State Agricultural College, which later became Kansas State. Considering that his father could not read or write, it is amazing that Williston got as far as he did, but he was an inveterate book reader from the moment he learned his ABCs, so much of his education took place outside the one-room schoolhouse he attended in Manhattan.

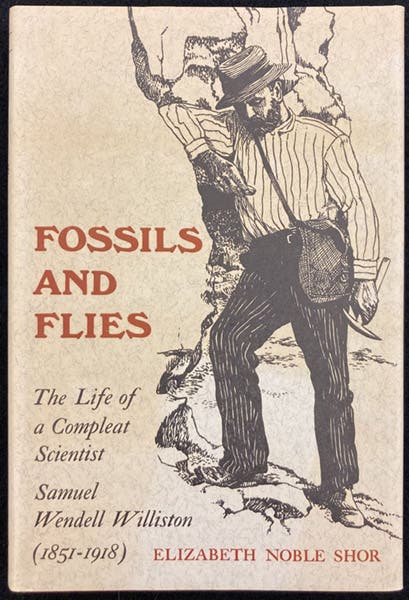

Drawing of Samuel Wendell Williston, based on a photo of 1891, dust jacket of Fossils and Flies: The Life of a Compleat Scientist, Samuel Wendell Williston (1851-1918), 1971 (author’s copy)

Like most professional naturalists, Williston started to collect things – leaves, rocks, fossils – while still a child, and he never stopped. In 1874, he went to work as a field man for Othniel Charles Marsh, a professor at Yale who was one of the first Easterners to come West, looking for dinosaur remains. Williston was instrumental in finding and helping to remove the wealth of dinosaur bones found at Como Bluff, Wyoming, in 1877. Williston was good at this, but he chafed at the restrictions Marsh imposed on his assistants, denying them any chance to publish on their own. In 1880, Williston moved to New Haven, not to be near Marsh, but rather to study medicine at Yale, and to pursue the collecting of Diptera, better known as flies. He became quite an authority on flies, about which we will say little more in this post, since flies are not as picturesque as fossil reptiles, and also because I know little about flies.

Willison returned to the Midwest in 1890, when he took up the post of professor of geology and paleontology at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, at the personal invitation of Francis Snow, the new Chancellor. He had a hard time deciding between Manhattan and Lawrence – Kansas State wanted to hire him as well – but he liked Lawrence better, and he was able to sell a meteorite he had found for a tidy sum and build himself a fine house, with which he lured his wife from New Haven.

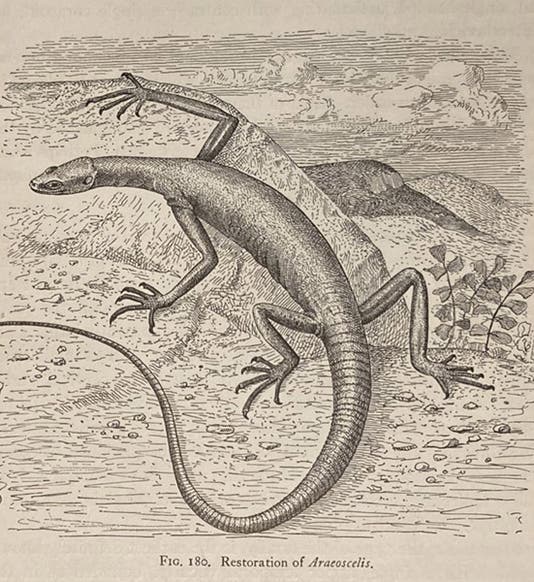

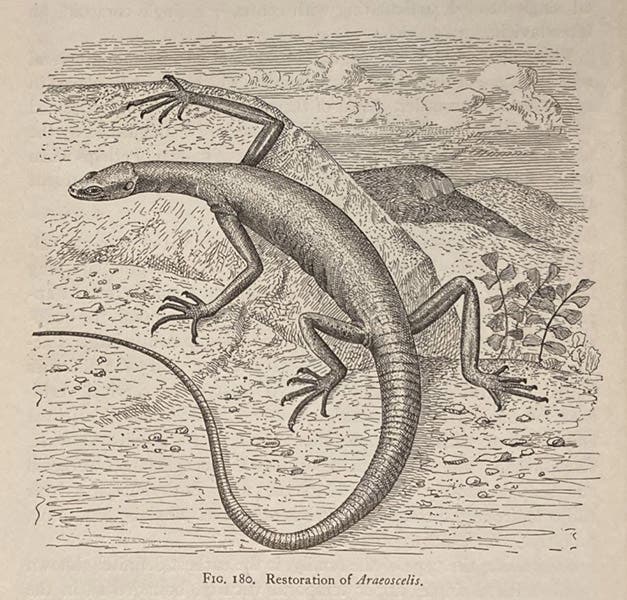

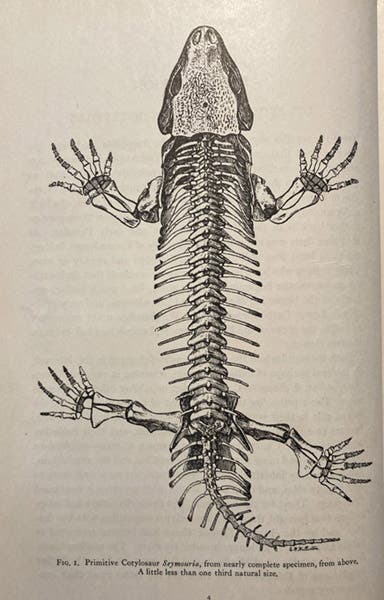

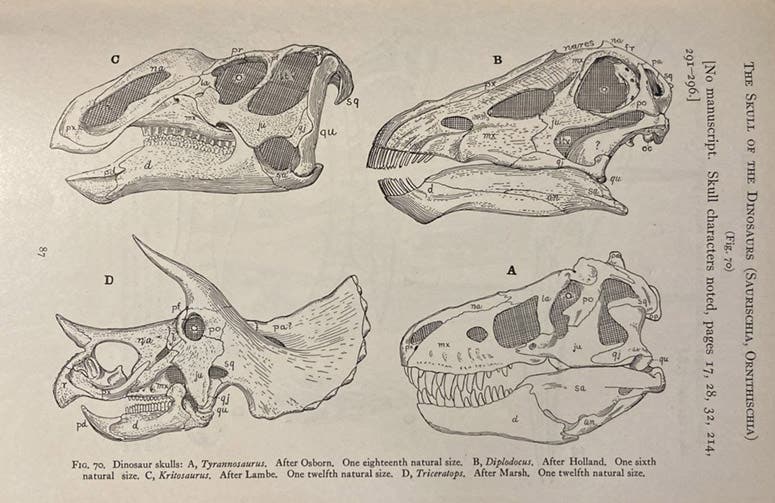

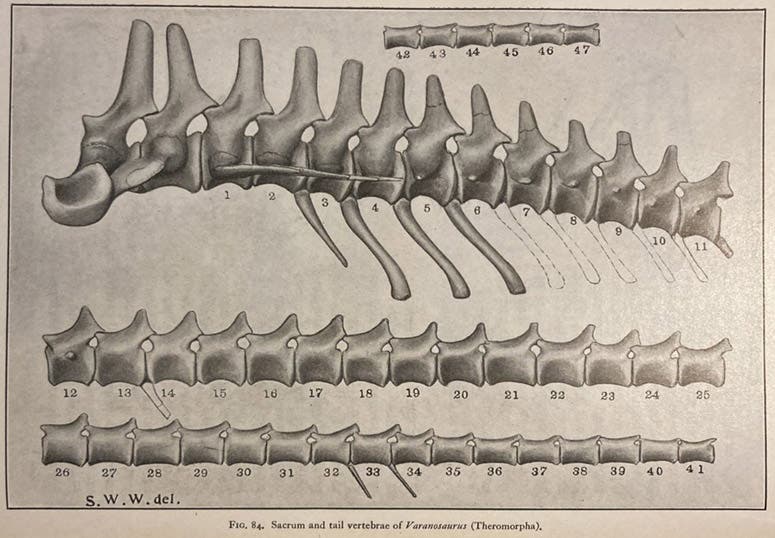

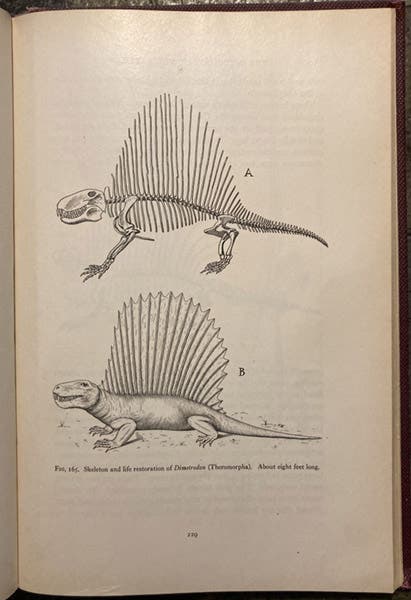

Williston moved to the University of Chicago in 1902, which was not as happy a time as at Lawrence, because of financial problems at the university. But Williston was a great teacher, and he began to turn out monographs on both reptiles and flies, making him one of the few naturalists at any time who was an international authority in two quite unrelated fields. We own his last work, The Osteology of the Reptiles, and all but one of our images here were taken from this book. Williston was a fine illustrator, and he did all the drawings for this book. He died before it was complete, and it took 7 more years for his editor, William King Gregory, to find a publisher and get it through the press. The illustrations, nearly all line drawings, are wonderful, and show mostly skeletal reconstructions, with some life restorations thrown in. A book with even better illustrations is Williston’s Water Reptiles of the Past and Present (1914), which has many more restorations, including several habitat restorations, the best kind of dinosaur restoration, made popular by Charles Knight. This link will take you to one of those, and indeed, to the entire book, which has been scanned and placed online at archive.org. We will try to find a copy for our collections.

There are very few portraits of Williston (who, incidentally, went by the first name Wendell, not Samuel). The one shown on Wikipedia, of a very rough-hewn young geologist, is low-resolution; you get a more attractive version of the portrait from the dust jacket of Elizabth Nobel Shor’s biography, Fossils and Flies: The Life of a Compleat Scientist, Samuel Wendell Williston (1971; second image). The biography, published over 50 years ago, is excellent, and made good use of Williston’s “Recollections,” his surviving autobiographical manuscript, cut short by his death.

One of the curious features of Williston’s time at Kansas is that there seems to have been very little interaction with Lewis Lindsay Dyche, the renowned professor of natural history at Kansas at the same time as Williston. Dyche comes up only twice in Shor’s biography, and then only incidentally. One would think that a skilled taxidermist (Dyche) and a talented animal illustrator (Williston) would have had a great deal in common with one another. Perhaps there lies another story here, to be unraveled and told someday.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.