Scientist of the Day - Samuel W. Woodhouse

Samuel Washington Woodhouse, a physician and naturalist, died Oct. 23, 1904, at the age of 83. He was born in Philadelphia in 1822, the son of a naval officer who was not often home; his mother had died in childbirth when he was young, and he was raised by his aunt. He was a bird hunter as a youth, which probably led to his interest in natural history in general. He got to know several naturalists at the Academy of Natural Sciencs in Philadelphia, not far from his house. He became friends with Spencer Baird, who would soon become the assistant secretary at the new Smithsonian Institution. After a short and unhappy stint as a farmer, Woodhouse entered the medical school at the University of Pennsylvania in 1845, and was invited to be a member of the Academy that same year. He was 24 years old. He was about to set up a private practice in Philadelphia when the Army came calling. Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves of the Corps of Topographical Engineers was being sent to Oklahoma in 1849 to conduct a Boundary Survey for the Creek Indian Nation, and he needed a physician-naturalist to accompany his small band of troops. Baird recommended Woodhouse, and off Woodhouse went, on his first military expedition into the west, where, in addition to caring for the ailments of soldiers, he found an exciting variety of plant and animal life, which was not new to others, but was new to him.

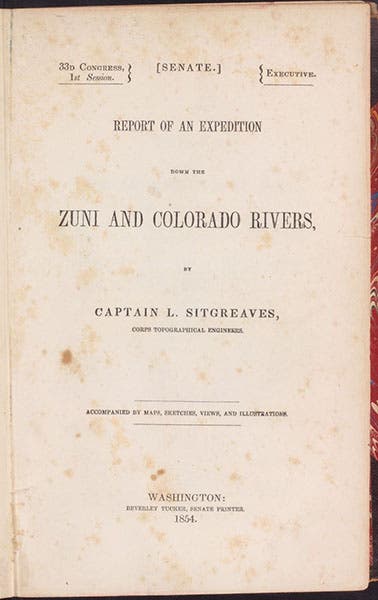

In 1851, Sitgreaves was tapped to lead an exploratory military expedition from Zuni Pueblo in what is now New Mexico to the Colorado River, and then all the way to the Pacific coast. His orders were to find a route for a wagon road from Santa Fe to San Diego. Sitgreaves needed a physician-naturalist, and he apparently had gotten along well with Woodhouse, for he invited him along again. Woodhouse was eager to go. Also included in the Sitgreaves expedition were two artist-brothers, Richard and Ned Kern, who were also from Philadelphia.

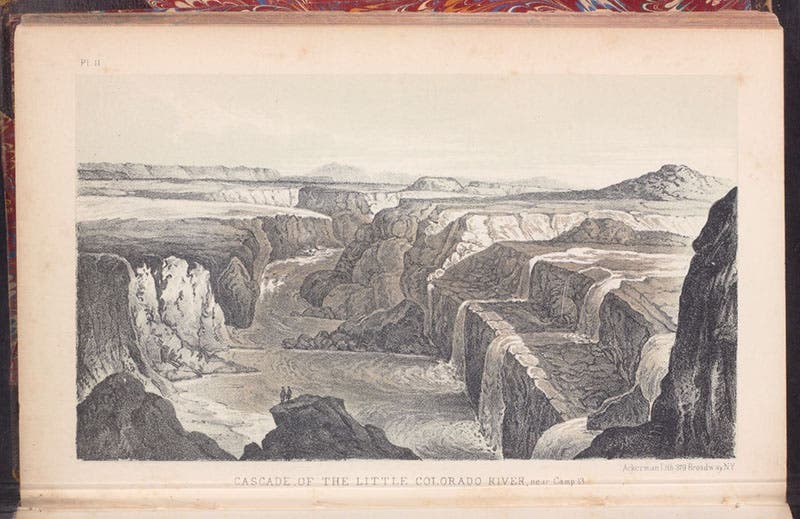

The expedition spent some time at the Zuni Pueblo before setting out along the Zuni River, which was found to be not much of a river at all. They progressed along the Little Colorado River, and then the Colorado, where it turns due south to Yuma. This was the first official expedition ever onto what is called the Colorado Plateau, the area south of the Four Corners area, so much of the flora and fauna were new to naturalists, and Woodhouse encountered a variety of new species, which he collected by shooting and skinning, as was the custom. He kept a diary, which survives in 4 volumes in the Library of the Academy in Philadelphia, and which was edited and published in 2007 as From Texas to San Diego in 1851: The Overland Journal of Dr. S.W. Woodhouse. The book is about half Woodhouse and half annotations by the editors, Andrew Wallace and Richard Hevly, who were very helpful in putting Woodhouse’s narrative into context.

Falls on the Little Colorado River, engraving after a sketch by Richard Kern, in Report of an Expedition down the Zuni and Colorado Rivers, by Lorenzo Sitgreaves, scenic plate 11, 1854 (Linda Hall Library)

The most famous part of the diary details the aftermath of Woodhouse's encounter with a rattlesnake, which he had grabbed too far back from its head, and which was able to turn and bite him on the finger. He survived, but barely, and his account of the remedies he applied, inside and out, to reduce the pain and swelling, is sobering indeed. But he did survive, although the attack considerably delayed Sitgreaves’ departure from Zuni Pueblo.

They eventually made it to San Diego (having discovered it was impossible to build a trail large enough for wagons), and returned by boat via the Isthmus of Panama. There was no canal yet, nor railroad, so they crossed at Lake Nicaragua, and then back to New York by ship, arriving in April of 1852. Woodhouse had to wait 6 months for his specimens to arrive, but when he had them in hand, he wrote his natural history report.

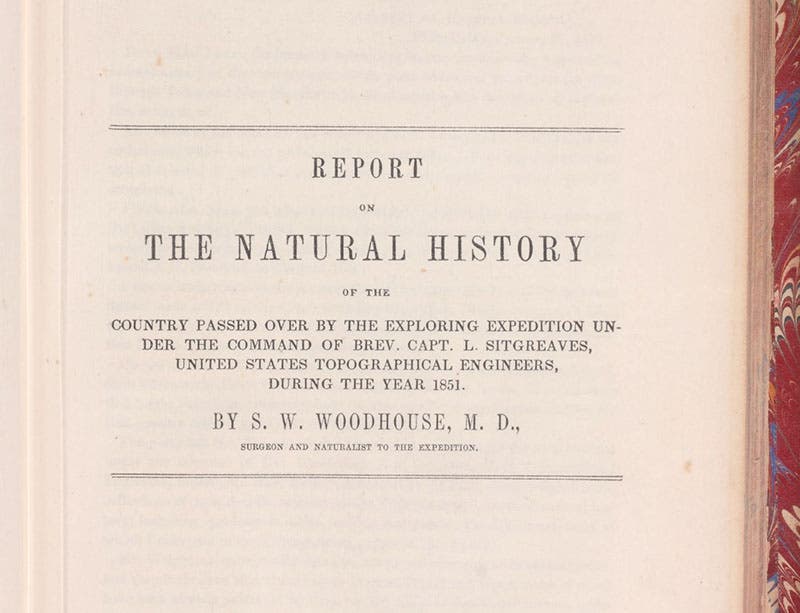

The Sitgreaves expedition was one of the first of many forays by topographical engineers into the American West, preceded only by the Simpson expedition of 1849, from Santa Fe to Zuni Pueblo, but already a custom was established of publishing as soon as possible a government report, written by the commanding officer, with contributions by the naturalists, and illustrated by the artists that went along. The Sitgreaves Report was published by the government in 1853 (third image). Sitgreaves’ own report is 25 pages long. Woodhouse’s “Report on the Natural History,” which follows, is 160 pages long. The publication really should be called the Woodhouse Report. 3000 copies were printed in 1853, and the Report must have been widely distributed, for the next year, 2000 more copies were called for. We have a copy of the second issue of 1854, from which our images are taken.

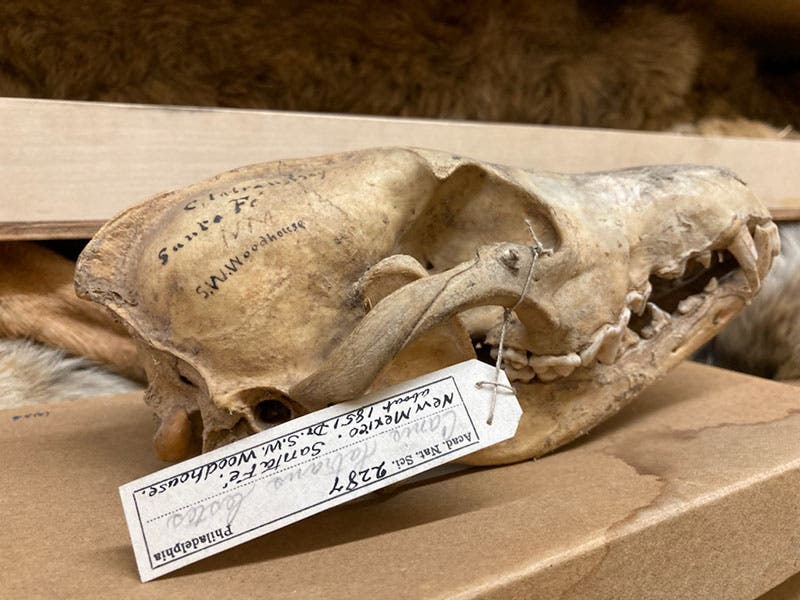

The preserved specimen of Pityophis affinus, gopher snake, , caught by Samuel W. Woodhouse, New Mexico, 1851, in the collections of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Philadelphia (photo courtesy of Robert M. Peck, curator and senior fellow)

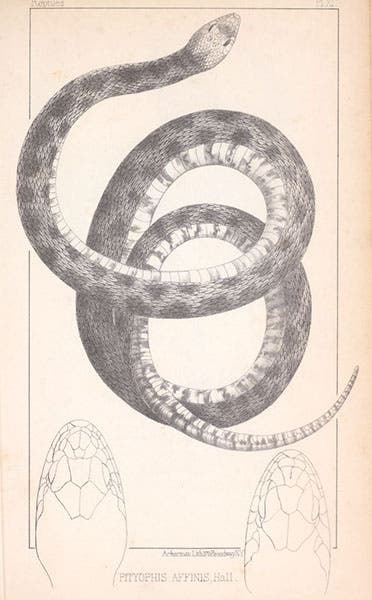

The good-looking part of the Report contains the lithographs made after sketches by Richard Kern. Many are scenic in nature, and we showed some of those in our post on Sitgreaves, and one new one here, of the falls of the Little Colorado (fourth image). But Kern also made drawings of Woodhouse’s specimens; we show here a delightful lithograph of a pocket mouse (first image). We also include a drawing of a gopher snake (sixth image). The snake is not that attractive, and I would not ordinarily include it, but Woodhouse’s specimen from which the drawing was made just happens to survive in the collections of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. The curator, Robert M. Peck, kindly sent me a photo of the pickled ophidian (seventh image). He also sent a photo of a coyote skull collected by Woodhouse. There is no lithograph of a coyote in the Sitgreaves Report, but we include the photo anyway, because you can easily read the identifying tag with Woodhouse’s name (eighth image).

A skull of Canis latrans (coyote) caught in Santa Fe in 1851 by Samuel W. Woodhouse, in the collection of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Philadelphia (photo courtesy of Robert M. Peck, curator and senior fellow)

There is a fine oil portrait of Woodhouse, painted by Edward Bowers shortly after Woodhouse returned from the Southwest, in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Bivouac on Jan. 26 [1854], chromolithograph from a sketch by Balduin Möllhausen, Explorations and Surveys for a Railroad Route from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean: Route near the Thirty-Fifth Parallel, by Amiel W. Whipple (Pacific Railroad Report, 3), 1856 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/55140a90-4b5d-4dac-832c-5def5cb51a10/Whipple1_cover.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)