Scientist of the Day - Samuel Stevens

Samuel Stevens, a natural history broker, was born Mar. 11, 1817. In the late 1840s and 1850s, Henry Walter Bates and Alfred Russel Wallace travelled tens of thousands of miles in the Amazon basin (Bates and Wallace) and the Malay Archipelago (Wallace alone), collecting hundreds of thousands of exotic beetles, butterflies, and occasional mammals and plants. How do you suppose they were able to afford such sustained expeditions? Charles Darwin collected his way around the world on the Beagle in the 1830s, but his family was wealthy, and his father paid all the bills. Wallace and Bates were not landed gentry and seldom had a farthing between them. They were able to travel so extensively and buy collecting jars and food to eat because they had an agent, Stevens, who paid their way and helped sell their collections.

In 1848, Stevens founded the Natural History Agency in London, which sponsored collectors and in exchange was given exclusive rights to a part of their collections, which Stevens sold to stay-at-home collectors and museums for a 25% commission. Stevens outfitted Wallace and Bates, essentially paying them advances against the future sale of their collections. When Wallace was shipwrecked on the way home from the Amazon in 1852 and lost nearly all his possessions and collections, Stevens bought him new clothes and put him up in his own home until he could fend for himself. Wallace and Bates were both such prodigious collectors that Stevens still seems to have made quite a profit from the entire enterprise. It is fair to say that without Stevens, or someone like him, many of the great collecting expeditions of the mid-Victorian period would never have taken place, including those of Wallace and Bates.

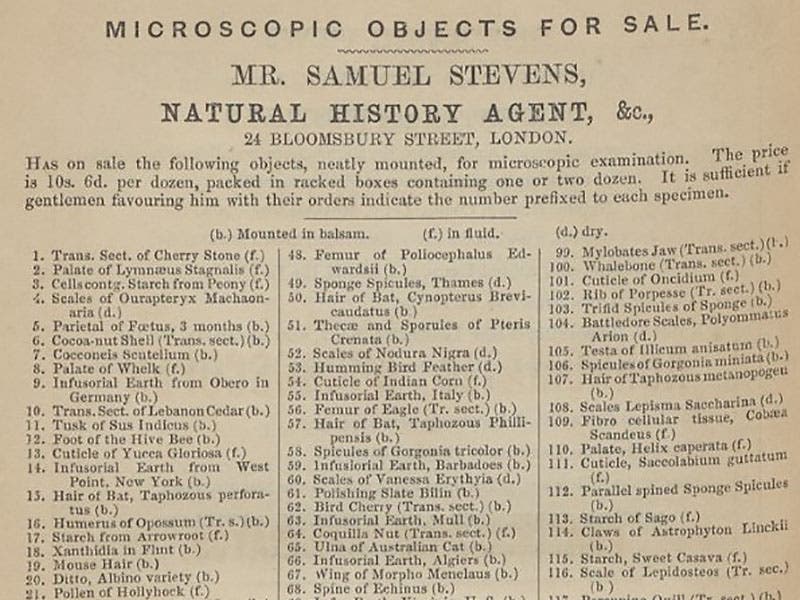

Stevens was active himself in the London social science scene, being a member of the Entomological Society and the Linnean Society, and often touting his clients and their finds at meetings. Stevens also went into the "microscope slide" business, responding to the rising popularity of microscopes among the general public in the 1850s; some of his prepared slides can be seen in our opening image. Stevens even inserted a full-page ad for his slides in several microscope handbooks published in the mid-1850s; we show you one from our copy of Jabez Hogg, The Microscope: Its History, Construction, and Applications, 1856 (second image, above).

In 1860, Stevens sold a pair of Croesus butterflies (Ornithoptera croesus, or the Golden Birdwing) that Wallace had sent him (and described to him passionately in a letter) for the whopping sum of £6 pounds, an enormous price at the time. The Croesus was perhaps the most spectacular butterfly discovered by Wallace in Indonesia. The Museum of Natural History at the University of Oxford acquired a specimen of this butterfly from a collector in 1871, who must have acquired it from Stevens. It is the top specimen in the photo (third image, above).

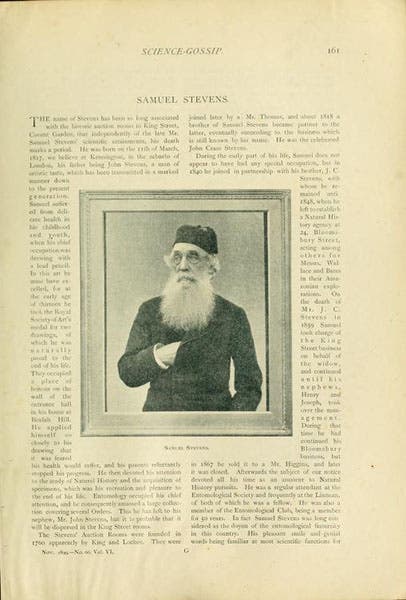

Stevens died in 1899 at the age of 82. There was a photograph of him in an obituary in the delightfully titled Science Gossip for that year, a journal of which we have a few issues, but not this one (image above). His own butterfly collection was sold at auction in 1900 at J. Stevens Auction Rooms, run by his nephew Henry. Since Stevens had 100,000 specimens, and some of the finest specimens brought £7 and £8 apiece, at a time when a pound was worth about £125 in today’s buying power, it must have been a good day for both the Stevens estate and the Stevens Auction House.

Those interested in learning more about Stevens may consult this website, which also provided us with leads to several of our images.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.