Scientist of the Day - Samuel Pozzi

Samuel-Jean Pozzi, a French surgeon and gynecologist, was born Oct. 3, 1846, in Bergerac, Dordogne. He came to Paris to study medicine in 1864, survived the revolution of 1870, studied with Paul Broca, and eventually became a hospital surgeon at the Hôpital de Lourcine-Pascal in Paris, where he would institute a number of reforms. He had made his first (of many) trips to Great Britain in 1876, where he met the Scottish physician Joseph Lister, who was incorporating antisepsis into his medical practice, using carbolic acid to protect wounds from infection. Pozzi took Lister's "rules of antisepsis" back to Paris and installed them in his hospital, where he became head of surgery in 1883. He soon added "asepsis," the sterilization of instruments and the operating room to keep the sources of infection out.

Pozzi soon began to specialize in abdominal surgery, perfecting new techniques of laparotomy (opening of the abdominal wall; second image), and in gynecology, a discipline that he essentially invented. He removed ovarian cysts and fibroid tumors, and performed hysterectomies. At first, his patients were mostly poor, because the hospital did not allow him to have a private practice. But by the 1890s, this changed, and he acquired an extensive clientele, mostly of high society Parisiennes, because, as you may have noticed, Pozzi was extremely handsome. Women patients flocked to him, both in and out of the consulting room, and he did not turn them away. In 1879, Pozzi had married a wealthy heiress, but their marriage soon lost its fire, much to his distress, although the couple had three children. In the 1880s and 1890s, Pozzi had affairs with a large number of women, most notably the actress Sarah Bernhardt (this affair soon morphed into a lifelong friendship, as well as a doctor-patient relationship).

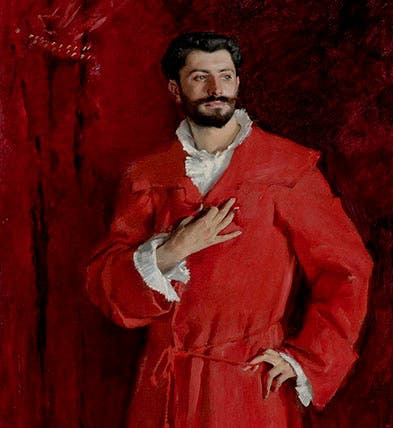

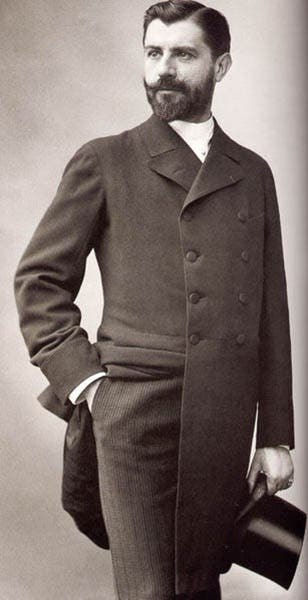

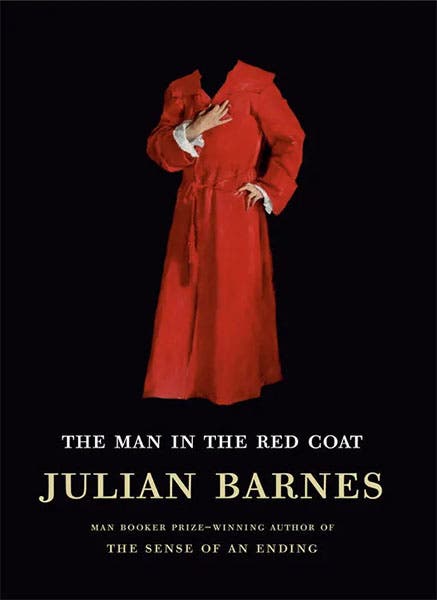

The portrait in red that you have no doubt already admired (first image) was painted in 1881 by John Singer Sargent, an American expatriate to Paris, who was introduced by Broca to Pozzi, and who apparently found Pozzi an irresistible subject. The portrait is titled, amusingly, Dr. Pozzi at Home, apparently a home quite different from yours and mine. Julian Barnes, the English author of Flaubert's Parrot and other masterful studies, published a book not so long ago (2019) about La Belle Époque, a kind of collective biography of many Parisian glitterati, in which Pozzi plays a prominent role, so much so that Barnes called his book The Man in the Red Coat, and featured a detail of Singer's portrait on the dust jacket of the English edition; the U.S. edition has just the coat, with Pozzi magically excised (fourth image). I think Barnes put Pozzi at the epicenter of his narrative because Pozzi contrasted so sharply with Barnes’ other subjects, in that he was congenial, considerate, and seemed to have no enemies (or just one, as it turned out).

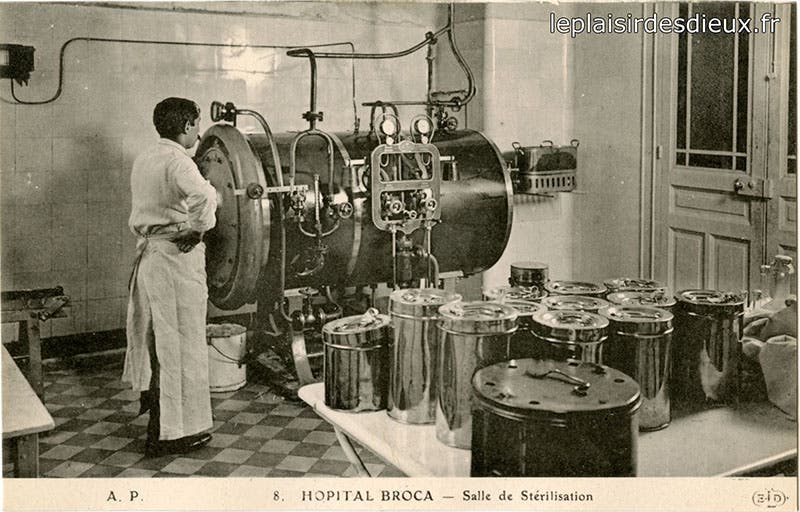

Pozzi came to the United States twice, in 1893 and 1904, both times to represent France at a world's fair, first in Chicago, then in St. Louis (with a stop off in Montreal). He spoke perfect English, which made him popular with his American hosts. Pozzi was impressed with American hospitals, their equipment, and their nurses (who were paid about 4 times what nurses in Paris received). He was also awed by the new Mayo Clinic, established in 1889 in Rochester, Minn. When he returned to Paris (the Hôpital de Lourcine-Pascal had been renamed the Hôpital Broca), he installed American. ventilation equipment in the Broca, and separate rooms for antisepsis, instrument sterilization (fifth image), even a chloroform room. Broca believed strongly that a hospital stay should be a pleasant experience, and he personally sought out artists to decorate the walls of the hospital to make it a cozier place (sixth image).

Barnes decorated the end papers of his book, and many of the interior pages, with tiny portrait cards from the early 20th century, included by the grocer Felix Potin in packages of chocolate. Pozzi was on two of those cards, and since there were some 1500 cards issued in three series, so was nearly everyone else from La Belle Époque, as well as some adopted sons and daughters, including Marie Curie. I have never collected any of these (although I will now keep my eye out for the two Pozzi cards, as well as the Madame), but since there were 1500 of them, there are a lot to choose from, especially if you are interested in late 19th-century French art and literature.

Pozzi served as a military surgeon in World War I, but his military career was cut short on June 13, 1918, when an unhappy former patient walked into his office and shot Dr. Pozzi three times, once in the stomach, and then turned the gun on himself. The abdominal wound turned out to be the fatal one for Pozzi, and all of his surgical and antiseptic innovations could not save him.

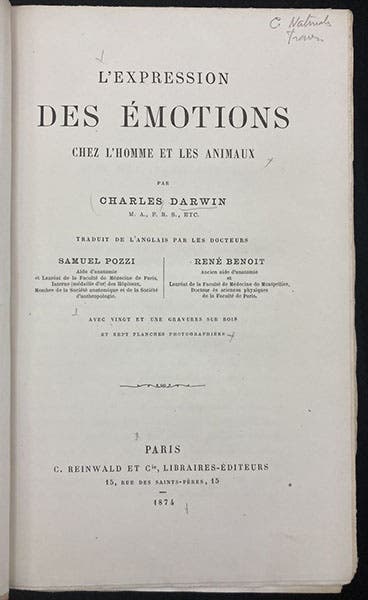

As a coda of sorts, and to end on a brighter note, we have a book by Pozzi in our library. Not his massive Traité de gynécologie clinique et opératoire, published in 1890 and translated into English, German, and four other languages – we do not collect medical works, and this book, influential though it was, would be out of scope for us. But in 1873, Pozzi was prevailed upon to translate Charles Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals into French. We have Pozzi's (and his co-author’s) published translation (1874) in our history of science collections (seventh image).

Sargent’s Dr. Pozzi at Home hangs in the Hammer Museum on the UCLA campus in Los Angeles (eighth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.