Scientist of the Day - Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys, an English diarist and civil servant, was born Feb. 23, 1633. Pepys is now best known for his diary, but as the diary was kept in secret, and in shorthand, and was not published until 1825, in his own time Pepys was unknown as a diarist, but highly regarded as an administrator for the Royal Navy and as a convivial man-about-town, fond of plays and wine and sociable women when he was away from his wife and home. His diary was begun on Jan. 1, 1660, on the eve of the restoration of King Charles II (whom Pepys helped bring from Holland, where Charles was waiting out the Interregnum), and it ceased in 1669, when he had problems with his eyesight and thought diary-writing might be the cause. So the diary recorded only the events of a decade, but what a decade, with the Restoration, the founding of the Royal Society, the Great Fire, the Plague, and a spate of Restoration comedies everywhere, performed by the likes of Nell Gwynn. Pepys participated in it all, and then he wrote it all down. His notes of the early days of September in 1666 are one of our main sources of details on the progress of the Great Fire; you can read his jottings for Sep. 2-5 here. Pepys’ first portrait was painted in this same year by John Hayls; it hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London (first image)

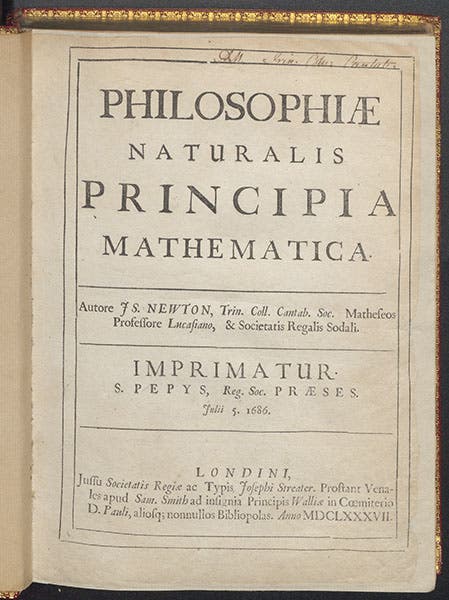

Pepys' place in a Scientist of the Day blog stems from his association with the Royal Society of London. He did not have much interest in natural philosophy, but neither did many of the members, who regarded the meetings and dinners as social occasions. But in 1684, Pepys was elected President of the Royal Society, and he was still in the chair in 1686 when Edmund Halley brought him a book manuscript from Isaac Newton at Cambridge and asked if the Society would publish it. As it happens, the Society was flat broke, having spent far too much money on the publication of Francis Willughby's book of fish engravings in 1685, but when Halley said he would bear the publishing costs, Pepys gave it his blessing. And that is why the title page of Newton's great Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica has Newton's name as author across the center, and just below, the word IMPRIMATUR , in a ridiculously large font. The line following reads, in the same size font as the attribution to Newton: "S. PEPYS Reg. Soc. PRAESES , Julii 5, 1686.” Scientists everywhere have been so pleased ever since that Newton's work met with Pepys' approval. It is coincidentally interesting that three years later, in 1689, Sir Godfrey Kneller painted portraits of both Newton and Pepys. If you want to see Pepys’ portrait, it is on display at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich (third image, below). If you want to see Newton’s, you need to get a personal invite to Farleigh House from the Earl of Portsmouth, or settle for this not very good reproduction on Wikipedia.

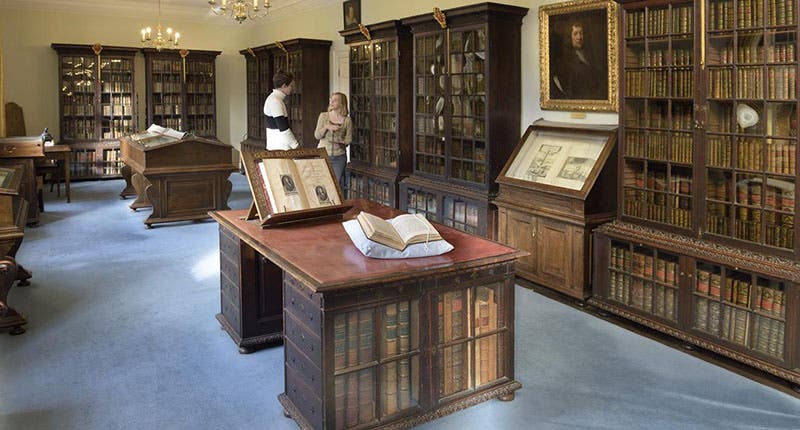

Pepys was an avid book collector, and his library of some 3000 volumes (along with his custom-built bookcases) now occupies the Pepys Library building at Magdalene College, Cambridge (fourth image, just below). The nine manuscript volumes of the Diary are there as well. There is a view of the exterior of the Library building a little further down (fifth image).

Pepys also loved music, the low-brow variety, and his collection of thousands of contemporary ballads (also housed in his Library) is reputedly a unique asset to musicologists. Pepys played several instruments and even wrote the occasional song. You can hear one of them, “Beauty Retire” performed at this link. (In the Halys portrait of 1666, Pepys is holding the music for “Beauty Retire”). While you are on YouTube, you might also check out this ditty about Pepys, which is entirely spurious (Pepys did not die in a fire), but still amusing and very well sung (it was recorded at the BBC Proms in 2008). Be forewarned: if you watch this, you will be singing it under your breath for the rest of the day. The occasional appearance of a wheel of cheese in the video is a veiled (a very veiled) reference to Pepys’ confession that, as the Great Fire was advancing, he and a friend dug a hole in the friend’s back yard and Pepys placed in it a treasured possession, a huge wheel of “Parmazan” cheese. He has been the butt of cheese jokes ever since. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)