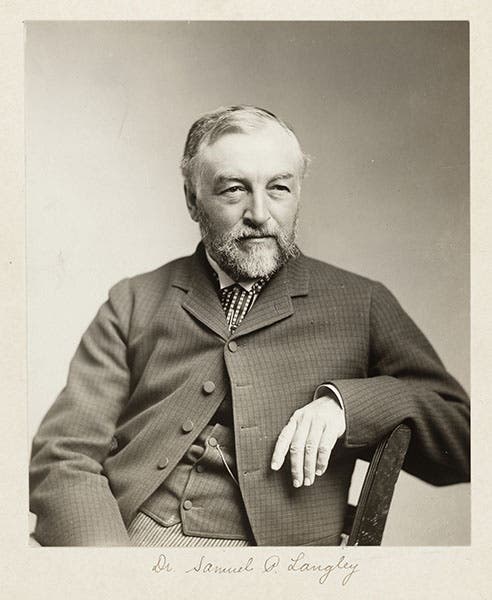

Scientist of the Day - Samuel P. Langley

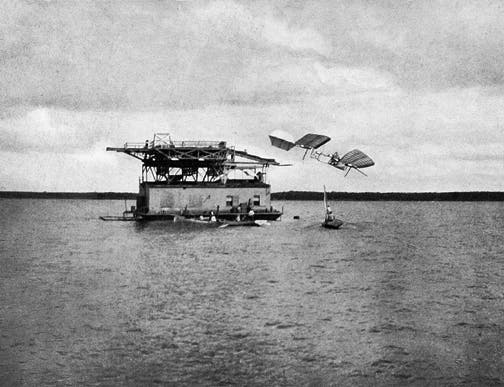

Samuel Pierpont Langley, an American astronomer and aircraft builder, was born Aug. 22, 1834. Langley was director of the Allegheny Observatory in Pittsburg, and successfully oversaw its revival after it had fallen into disrepair, engineering its alliance with the University of Pittsburg. In 1887, Langley became the 3rd Secretary (i.e., Director) of the Smithsonian Institution, and he was responsible for founding the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Mass. But Langley apparently preferred working with his hands to administrative responsibilities, for he spent much of his time from 1890 on in attempts to build a powered aircraft. After some problems with early models, on May 6, 1896, he launched a small (14-foot wingspan) unmanned. steam-powered aircraft, Aerodrome 5 (first image), from the top of a houseboat in the Potomac River, and it flew half a mile before splashing down, which was about ten times farther than any other powered aircraft had flown. Alexander Graham Bell was there for the occasion, and photographed Aerodrome 5 in flight (third image). Langley had similar success with Aerodrome 6 that same year, achieving a 3/4 mile flight over the Potomac.

The U.S. Department of War became enthusiastic about Langley’s prospects and poured $50,000 into the development of a manned aircraft (the Wright brothers had about $1000 to spend on their Flyer). But Langley ran into difficulties building a full-sized aircraft that would fly. His problem was that he tried to make a larger aircraft by simply scaling up Aerodrome 5 and 6, and as any student of scale will tell you, this seldom works. Aerodrome A, as Langley called his large aircraft, had two sets of wings in tandem (like Aerodrome 5 and 6) and a large tail. But when he put a human in what passed for a cockpit and tried to launch Aerodrome A from his houseboat on Oct. 7, 1903, the plane went just a few feet and then plunged into the river (fourth image). He tried again on Dec. 8, and this time the tail immediately broke off the aircraft, and it again crashed into the river, nearly drowning the pilot. Nine days after the disaster second, the Wright brothers successfully flew their Flyer at Kitty Hawk, on Dec. 17, 1903. Langley’s incentive was gone, and he never again attempted a manned, powered flight. He died 26 months later, on Feb. 27, 1906.

Langley and the Wright brothers were on very good terms, both respectful of each other’s achievements, but after Langley’s death, the 4th Smithsonian Secretary, Charles Doolittle Walcott, took it upon himself to restore Langley as the father of human flight, at the expense of the Wright brothers. In 1914, Aerodrome A was dusted off, refurbished and modified, and on June 2, 1914, with Glenn Curtiss at the controls, it lifted off for about 5 seconds. That was enough for Walcott. He moved Aerodrome A into the Smithsonian, with a placard saying that Langley had built the first plane capable of manned powered flight. Orville Wright (Wilbur had died in 1912) was outraged and pointed out that some 35 changes were made to the plane that now enabled it to fly, and that Glenn Curtiss had just lost a patent-infringement suit brought by the Wrights and was hardly a neutral party. Walcott was unmoved by the protest, so in 1928, Wright sent the Flyer to the Science Museum in London, rather than allow it to go to the Smithsonian. After Walcott's death, the 5th secretary reviewed the case, and in 1942 issued a mea culpa (actually a sua culpa, since he blamed Walcott), saying that the Smithsonian had acted improperly, and that the Wright brothers deserved the credit as the first humans to successfully fly a manned powered aircraft. Eventually, in 1948, the Wright brothers Flyer was transferred to the Smithsonian and put on display, where you may still see it today, in the National Air and Space Museum.

Although Secretary Walcott’s behavior was outrageous, and Curtiss’s shenanigans deceitful and dishonest, it should be understood that Langley had nothing to do with this unfortunate aftermath, and he deserves a great deal of credit for making it respectable to attempt to build and fly manned, powered aircraft.

Aerodrome 5 and 6, which both flew successfully, are in the National Air and Space Museum, but are not on display. Aerodrome A, which never flew in its original configuration, hangs in the Museum right next to the Wright Brothers Flyer (fifth image). Go figure.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.