Scientist of the Day - Samuel Goudsmit

Samuel Abaham Goudsmit, a Dutch-American physicist, died Dec. 4, 1978, at the age of 76. Goudsmit was born in The Hague and studied physics at the University of Leiden under the great Paul Ehrenfest, who was a close friend of Albert Einstein. A photograph taken in Leiden in the 1920s shows the three physicists (second image). Goudsmit demonstrated his grasp of quantum mechanics in 1925, when he (and two others) proposed the idea of electron spin to account for a new quantum number discovered by Wolfgang Pauli. After obtaining his PhD, Goudsmit took a position in 1927 at the University of Michigan, where he would teach for nearly 20 years. This allowed him, a Jew, to escape the consequences of the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands. His parents were not so fortunate; both died in a German concentration camp in 1943.

During the War, Goudsmit worked for a time at MIT, and then agreed to join the Manhattan Project, where he must have become good friends with Enrico Fermi, who built the first atomic pile in Chicago in 1942 – there are many surviving photographs of the two together, usually in a playful mood (third image). Goudsmit was then appointed the chief scientific advisor to what was called the Alsos mission. By 1944, it appeared likely that the Manhattan Project was going to be successful in producing a bomb, and so it became imperative to learn whether the Germans had a bomb of their own, or if not, how close they were. So after D-Day, as the Allied troops forged on to Paris, a small group of soldiers and physicists, the Alsos team, followed immediately behind. Their mission was to capture any German nuclear physicists working on the bomb, confiscate any uranium or heavy water they might find, and locate any nuclear reactors and bomb assembly facilities, if there were any. The Alsos military leader, and the man most responsible for the success of the entire mission, was Colonel Boris Pash, but it was Goudsmit's responsibility to bring scientific expertise to the mission – to examine confiscated records, materials, and equipment and determine how far along the Germans were. Goudsmit probably earned his position not only because of his expertise in nuclear physics, but also because of his fluency in German, English, and French, as well as Dutch.

Fairly early on, after Strasbourg was liberated, Goudsmit concluded, from records captured there, that the Germans were not even close to making a successful bomb. But General Groves, in charge of the Manhattan Project, wanted absolute proof; he wanted to locate ever piece of equipment that might be used for a bomb and every scientist who knew how to use it, and he wanted it and them out of Germany and back in England or the United States. It wasn't Germany he was worried about now – he wanted to keep nuclear materials and atomic scientists out of the hands of the Russians and the French. When a huge store of uranium ore (some 1100 tons!) was discovered in a part of northern Germany that was scheduled to be partitioned to Russia, a frantic effort was made (successfully) to get the uranium out before the Red Army got in. Similarly, when a German not-yet-functional nuclear reactor was discovered at Haigerloch in Württemberg, in a part of southwest Germany that was slated to become part of the French partition, the Alsos team went in behind German lines to spirit the physicists and their reactor out of Germany, so that when the French got there, there was nothing nuclear left for the taking (fourth and fifth images). All of the captured German physicists and chemists were taken to England and confined there, as part of Operation Epsilon, about which you may read more at our post on Pash.

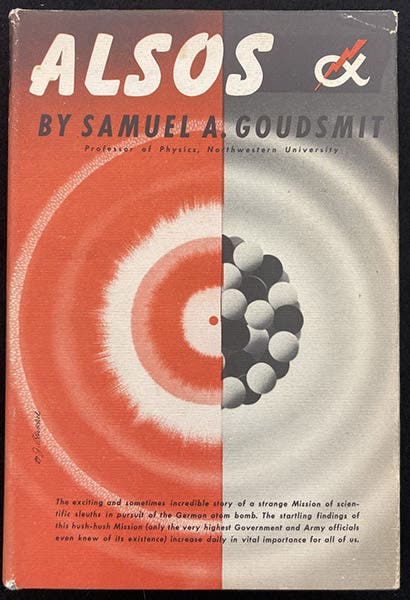

After the War, Goudsmit quickly wrote and published a book on his exploits, called Alsos (1947; last image), in which he took most of the credit for the success of the mission, which irritated Boris Pash more than a little. It took Pash another 20 years to write his own account of the mission and give himself the lion’s share of the credit. The truth is, both men were essential, even though the ultimate outcome of the Alsos mission was a negative conclusion – the Germans never came close to building a bomb.

If you are interested in more details of this fascinating mission, there is no dearth of source material. If you don’t feel like reading Goudsmit and Pash and sorting out the truth for yourself – although both wrote quite entertaining books – you can always read the short section on Alsos in Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (1986), always a good choice when inquiring into matters related to the Manhattan Project.

Dust jacket, Alsos (1947), by Samuel Goudsmit (author’s copy)

All of our images except the last were taken from an indispensable resource, the Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, at the American Institute of Physics, which you may access by clicking on any one of our images. There are hundreds of photographs there related to Goudsmit and the Alsos mission.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.