Scientist of the Day - Salvador Luria

Salvador Luria, an Italian/American microbiologist, was born Aug. 13, 1912. Luria left Italy for France in 1938, in the wake of the rise of Fascist anti-Semitism, and then he fled France for New York City in 1940, where the Rockefeller Foundation helped him settle in. Luria, inspired by the work of Max Delbrück, another refugee from Europe, worked on bacteria and the viruses that afflict bacteria, known as bacteriophages, or phages for short. In the early 1940s, little was known about the mechanism of heredity – the discovery of the structure of DNA was 10 years in the future. Most biologists doubted that bacteria had chromosomes, and no one thought that viruses did. Mutations in bacteria or viruses were unknown. In a series of experiments with bacteria and their phages, Luria and Delbrück not only showed that both bacteria and phages mutate, and so have genetic mechanisms, they further demonstrated that the variations from generation to generation are Darwinian rather than Lamarckian. That is, when a bacteria develops a new strain that is resistant to a particular phage, it does so at random, and not in response to the presence of the phage. So not only did Luria and Delbrück show that bacteria and viruses have genes, they proved that natural selection is the mechanism that is responsible for genetic change. The argument was statistical, but it was ironclad. For their work, Luria and Delbrück (along with Alfred Hershey) shared the Nobel Prize for Physiology in 1969.

Luria began his phage experiments after moving to Indiana University, and one of his first graduate students was James Watson. Luria suggested that Watson go to the Cavendish Lab at Cambridge in England for his post-graduate work and arranged an introduction to the director. At the Cavendish, Watson met Francis Crick, with whom he would work out the structure of DNA in 1953. Watson and Crick received their Nobel Prizes in 1962, 7 years before Luria and Delbrück received theirs. Life is like that, sometimes.

Luria didn't do many of the things that scientists of the 50s and 60s were famous for; he didn't climb mountains – he didn't even like to walk to the store. He couldn't abide nature worship, and he detested sports. But he had a social conscience of great expanse. Having grown up in Italy in pre-war times, he had strong feelings about the rights of social classes and about political systems that abuse those rights. One of his first public stands came when the United States – and the Soviet Union – began extensive nuclear weapons testing in the mid-1950s. Linus Pauling took the first step, writing a letter denouncing the morality of and the claimed need for nuclear tests, and Luria was one of the first 10 signatories to the letter. Before long, there were thousands of signatures by scientists all over the United States, and nuclear testing slowed down and then stopped. In 1963, after the Bay of Pigs invasion, Luria (now at MIT) found a better way to protest; he helped form a Boston consortium, called BAFCOPI (Boston Area Faculty Group on Public Issues), and they took out an ad in the New York Times protesting the morality and legality of the action. The advert made quite an impression, especially since a Bostonian was sitting in the White House at the time. This practice of using advertisements as vehicles for political protests continued as the Vietnam War reared its head, and again proved to be a powerful method of protest, since you didn't have to join an organization to have your voice heard – you just needed to pay your share of a newspaper ad and sign your name.

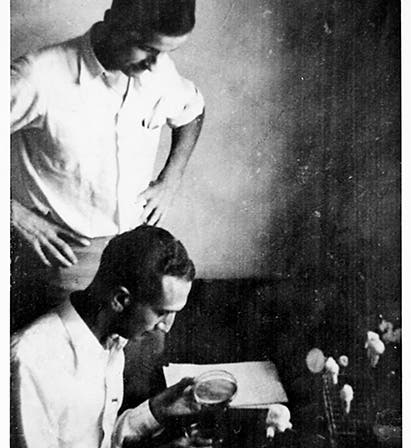

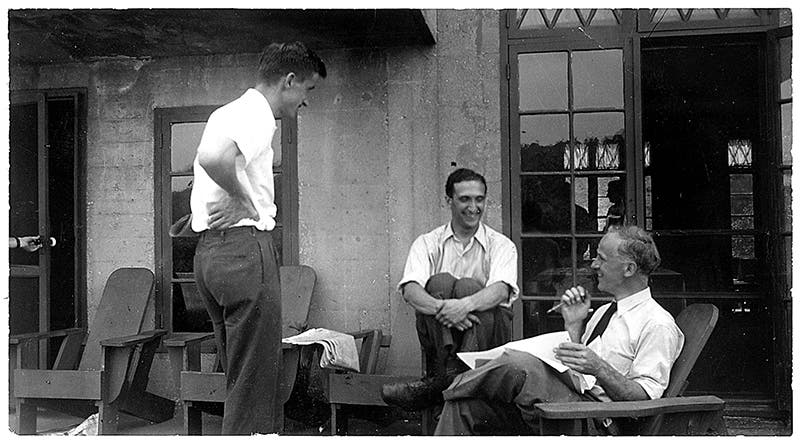

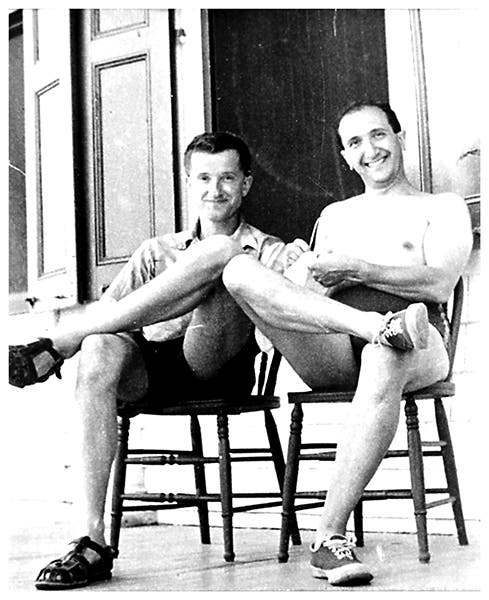

To return to the scientific arena, Luria also discovered restrictor enzymes – those tricky little molecules produced by bacteria that can snip DNA into pieces and thus protect against phages. Restrictor enzymes are now the essential tools for recombinant DNA technology and genetic engineering. Their discovery would seem worthy of another Nobel Prize, and it was, in 1978, but it didn't go to Luria, but to three younger microbiologists who built upon Luria's work. Luria probably did not mind. With a limit of three for a Nobel Prize, you can't reward everybody, and he did have a medal in his pocket. But as he later remarked, he wished the Nobel committee had waited just a little. The year after he received his Prize, they doubled the stipend. The photographs here show Luria and Delbrück at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1941 (first and second images); relaxing at Cold Spring Harbor in 1953 (third image); and Luria in his office at MIT, ca 1969, the year he received his Nobel Prize (fourth image). We should mention that Luria was a gifted writer, especially for a scientist for whom English was a third language. His autobiography, A Slot Machine, A Broken Test Tube (1984) is well worth reading, if you would like to step into the life of a man who worried a lot about his fellow human beings, especially the ones in charge. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.