Scientist of the Day - Rudolf Blaschka

Rudolf Blaschka, a Bohemian glass artisan, was born June 17, 1857. His father, Leopold, was a glass blower, and they moved to Dresden when Rudolf was a child. Leopold the father was master of a technique known as flame-working, whereby glass is softened using an alcohol lamp fed by an airstream pumped by a foot bellows. At first, Leopold made mostly costume jewelry and glass eyes. In 1863, Leopold was asked to have a go at making glass sea anemones for a Dresden museum. Marine invertebrates such as anemones or sea cucumbers were the bane of museum curators, since it is almost impossible to display actual specimens, which lose color and structure rapidly. Leopold had no real anemones to work from, so he found a book by Phillip Gosse, Actinologia Britannica (1860), with beautiful plates printed in color (a book we displayed in our 2009 exhibition, The Grandeur of Life), made working drawings from the printed illustrations, and soon flame-worked a variety of glass anemones. They were beautiful, and the museum director was delighted, and he urged Leopold to give up the glass eye business and start crafting glass invertebrates for museums. It was the best idea that director ever had.

Leopold taught Rudolf how to flame-work, and in the 1870s and 1880s, Rudolf and Leopold made a large number of glass invertebrates, many of which are now at Cornell University. They are exquisite, and a good subject for a future post, perhaps Leopold’s birthday, but today we are going to fast-forward to the 1890s and a project for which Rudolf played the primary role: crafting the glass flowers at the Harvard Museum of Natural History.

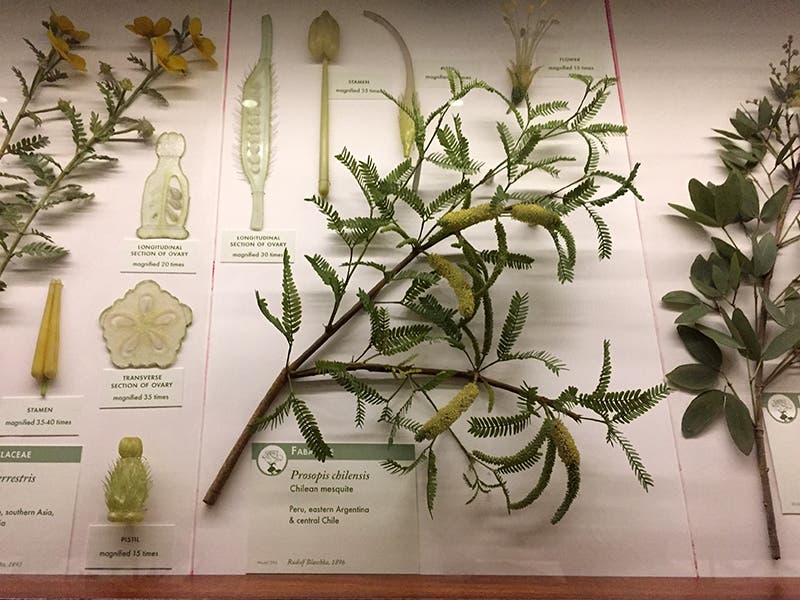

Louis Agassiz bought a number of Blaschka glass marine invertebrates for the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology (bought them right out of Henry Ward’s Natural Science catalog). In 1886, the Harvard professor of botany, George Lincoln Goodale, saw the Agassiz collection of sea creatures and got the idea of seeing if the Blaschkas were interested in making glass botanical models for display in the new Botanical Museum. Indeed they were. The first batch from Dresden arrived in pieces, due to customs misfeasance in New York, but Goodale showed the broken fragments to two wealthy Cambridge women, Mary Lee Ware and her mother Elizabeth, and they agreed to endow the collection. By 1890, a contract was signed whereby the Blaschkas would make botanical models only for Harvard, and the contract was renewed every ten years. As a result, Harvard has some 4000 models, representing over 800 different plants, and the "Glass Flowers", as they are called, are a wonder to behold.

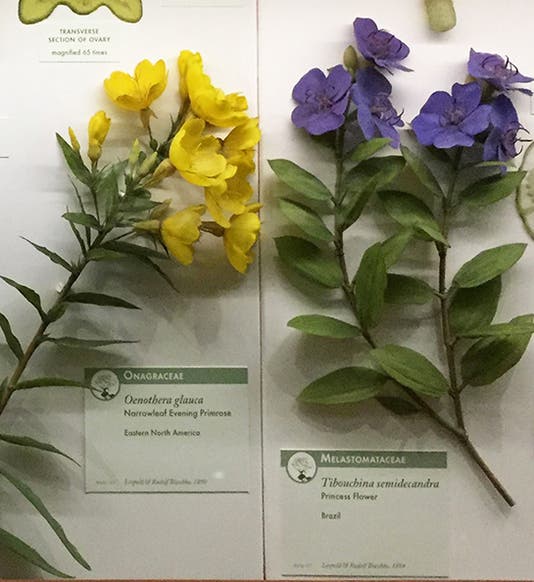

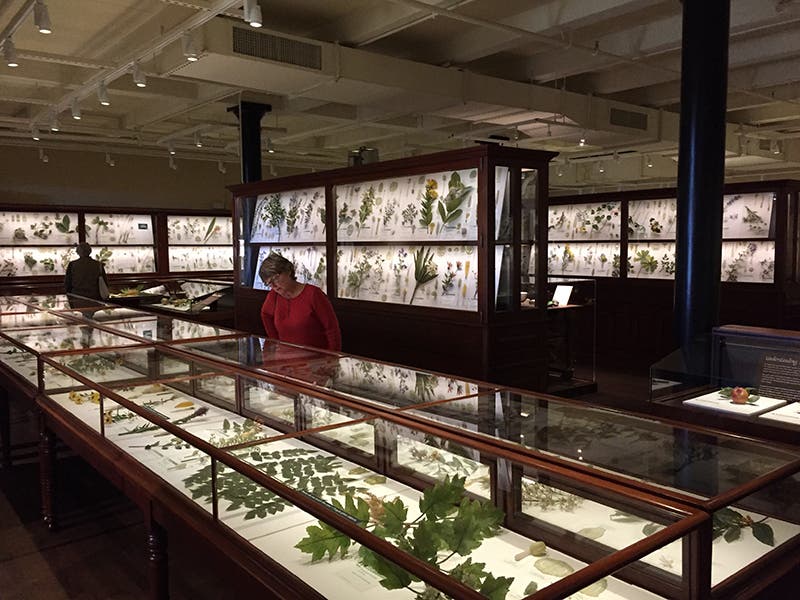

The exhibition recently emerged from several years of conservation; many of the flowers needed attention, and the original cases had to be refinished and partially rebuilt. The viewing space was also improved, as were the documentary labels. I saw the renovated exhibition just two months ago, and it is just gorgeous. The flowers are still as amazing as the first time I saw them. Everyone’s first reaction is, are they really glass? Well, they are – hand-worked, colored and painted glass. Modern flame-workers, the ones who restored the flowers, all agree that the Blaschkas were the best flame-workers who ever lived.

The photos here of the glass flowers are ones I took on my recent visit. You can find better and brighter photos on the Glass Flowers website.

But I rather like mine, since they capture the feeling of going down the dimly-lit aisles and being blown away by each newly-encountered case. If you go to Boston and Cambridge, you will be tempted by many fine museums, but if you skip the Ware Collection of Glass Flowers at Harvard, you will miss the greatest museum experience of them all.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.