Scientist of the Day - Roger Cotes

Roger Cotes, a British mathematician and astronomer, who might easily be referred to as "poor Roger Cotes," died June 5, 1716, at the age of 34. Cotes started out life well, recognized early as a gifted mathematician in Leicestershire, where he grew up. His uncle, John Smith, took an interest in young Roger, and Uncle John’s son, Robert Smith, would become a lifelong friend of Cotes and would do much to preserve and publish his papers. Cotes attended St Paul’s School in London, and then Trinity College, Cambridge, where he received his M.A. in 1706. Almost immediately, he was appointed to be the first Lumlian Professor of Astronomer at Cambridge. Life had been good, so far, to Roger Cotes.

But then Cotes came to the attention of Richard Bentley, Master of Trinity College. Bentley had been a terrific classical scholar, but once he became Master, he was determined to increase his personal fortune at the expense of the wealthy college. One of his ideas was to supervise the publishing of a second edition of Newton’s Principia – first printed in 1687 and now very hard to find – and as publisher, reap the profits. Newton did not respond well to Bentley’s urgings, since Bentley was not a mathematician, so Bentley selected Cotes to be editor and go-between. Cotes managed to get Newton interested in a revised edition, and the two worked together for three-and-a-half years, revising the book line by line and improving it greatly, with many sections completely rewritten by Newton and then reworked by Cotes. Since Newton was now in London, working at the Mint and presiding over the Royal Society, most of the editing took place at a distance.

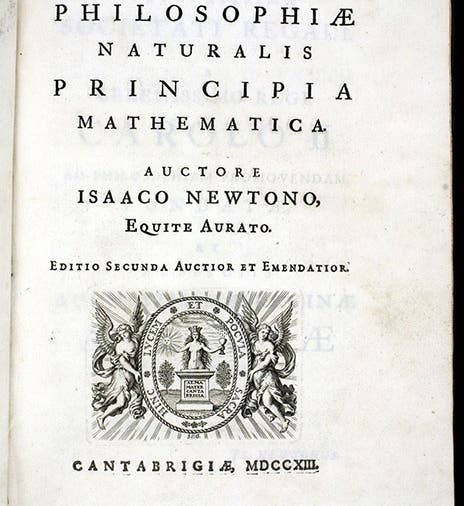

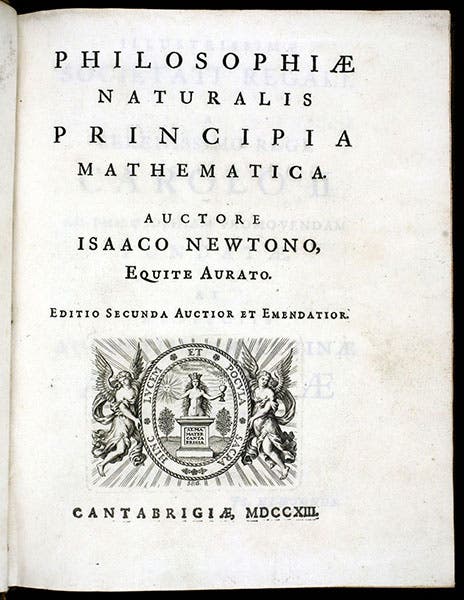

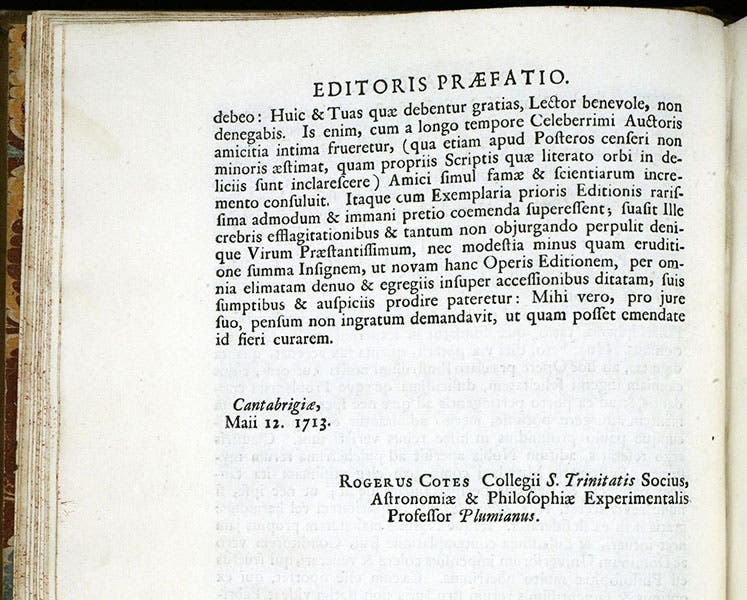

Cotes did quite a respectable job as an editor, pointing out many instances where proofs needed to be tightened up or redone, and keeping Newton on schedule. Cotes also wrote the editorial preface to the new edition, which ably responded to the criticisms of both the Cartesians and the Leibnizians. The second edition was finally published in 1713. If you look at the title page of our copy of the second edition (first image), there is no mention of Cotes’ role as editor. Indeed, there is no mention of Cotes anywhere in the book, except for his name at the end of the preface (third image). Newton had thanked Cotes in a draft preface of his own, but he suppressed that in the printed edition, and removed the one mention of Cotes in the text. As for other remuneration, Cotes received nothing. Bentely and Newton pocketed all the profits from the book, which sold well. None of it went to Cotes.

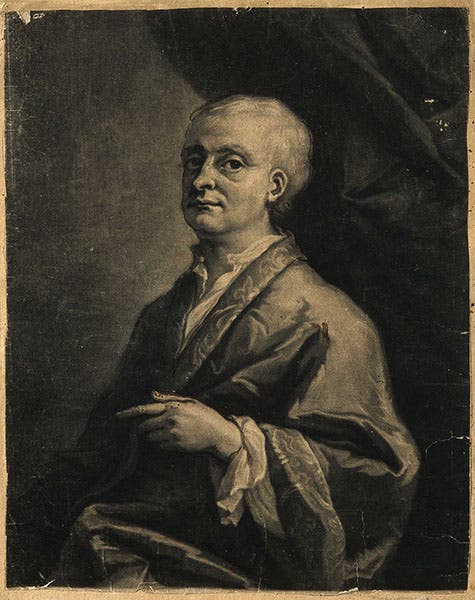

The only tangible reward for his 42 months of service was a thank-you gift that Cotes received from Newton in 1712, via Bentley. It was an engraved portrait – of Newton! I am sure that made Cotes’ day. Until recently, no one knew just what that portrait was, but the mystery was cleared up in 2012 by Bruce Bradley, the former Librarian for Rare Books at the Linda Hall Library, who published an article in 2012 in Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, titled "Newton's gift to Roger Cotes." Mr. Bradley demonstrated that the only possible candidate was a mezzotint after a portrait by James Thornhill, of which only a single copy survives, in the Wellcome Collection in London. We show it to you here (fourth image). Mr. Bradley was motivated to investigate because our library owns a different mezzotint portrait of Newton, and we were hoping it might be the one that Newton presented to Cotes. That turned out not to be the case. You can read Mr. Bradley’s article at this link, where you can also see our Newton mezzotint.

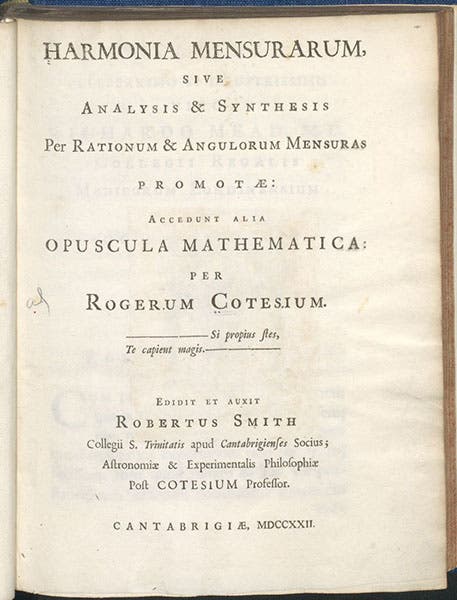

Cotes would probably have had a stellar mathematical career of his own, except that he came down with a “violent fever” in 1716 and died, only 33 years old. He had written many papers on such things as cubic spirals and quadratic equations, with many original conclusions. Fortunately, cousin Robert Smith stepped in and ensured their publication in a volume called Harmonia mensurarum (1722) which was handsomely printed, and which we have in our collections (fifth image). Smith succeeded Cotes as Lumlian Professor in 1716, and would later publish important works on optics and harmonics, which you can read about in our post on Smith. Our copy of the Harmonia has the armorial bookplate of Thomas Wright, who is probably not the cosmologist Thomas Wright of Durham. We include the bookplate, hoping that someone will recognize it (sixth image).

Cotes was buried in Trinity College Chapel at Cambridge. Much later, in Victorian times, the windows in the chapel were replaced with stained glass, and two of the windows, at the west end of the north and south aisles were devoted to portraits of “Trinity College Worthies.” The one on the north side has 8 portraits in glass, of which we show the top four (seventh image). Cotes is the second from the right, holding the reflecting telescope; he is flanked by Newton on the left and John Ray on the right. Bentley stands at the far left. Even though the windows were not put in place until 1875, they reflect belated recognition of Cotes’ contribution to the academic brilliance of Trinity College in the early modern era.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.