Scientist of the Day - Robert Millikan

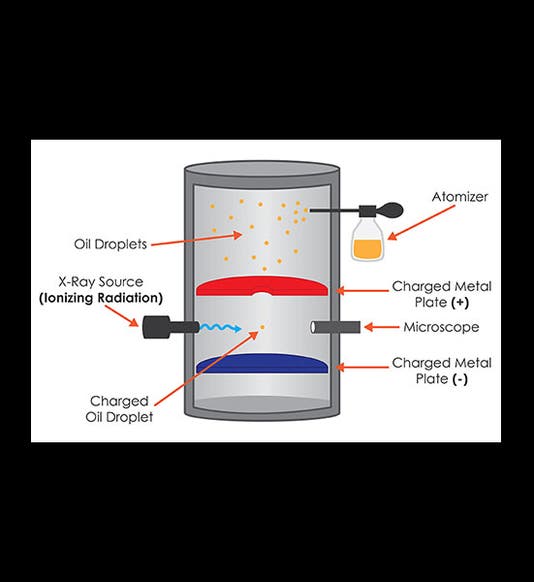

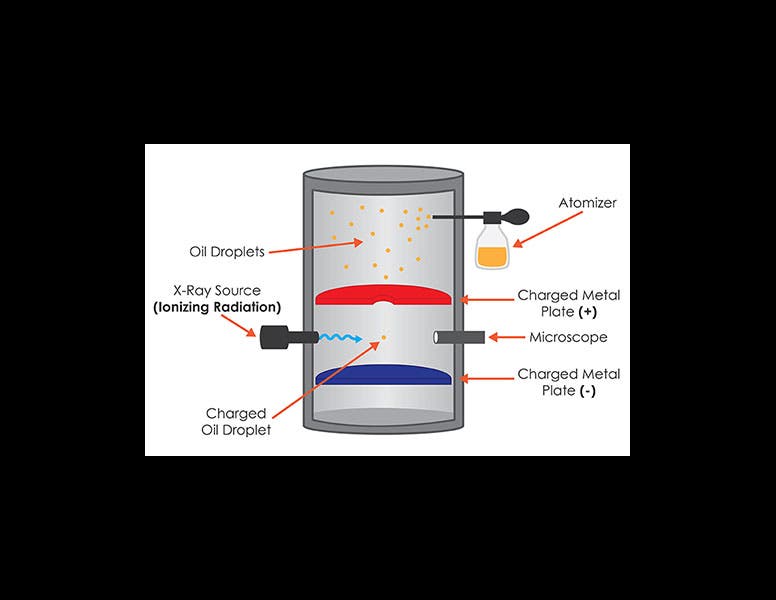

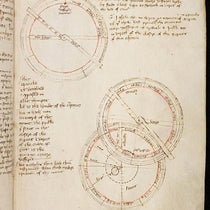

Robert Millikan, an American physicist, was born Mar. 22, 1868. In 1910, Millikan conceived a now-famous experiment to determine the charge on an electron. He used an atomizer to spray very fine droplets of oil into a closed container. Within the container, there were two electrical plates that could be charged. A small hole in the top plate allowed some of the oil droplets to float down toward the bottom plate. X-rays were directed into the chamber, where they ionized the oil drops, leaving them with a small electrical charge. Millikan then applied a negative charge to the bottom plate, so the plate repelled the negatively-charged oil drops, and by carefully controlling the voltage, Millikan could actually get them to stop and float in the air. He determined when all the forces had cancelled out by observing the oil drops through a small microscope. We see above a textbook diagram of the apparatus (first image) and a photograph of the actual equipment Millikan used (second image).

When Millikan measured how much charge was applied to the plates, and calculated what the rate of fall should be for an oil drop with no charge, he could determine the charge on each oil drop, and if one further assumed that each oil drop had attracted one, two, three, or more electrons, it was possible to look for the lowest common denominator--the charge on a single electron. Millikan did just that. For his troubles, Millikan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1923, and the “Millikan oil-drop experiment” became an instant classic, an exercise performed by tens of thousands of physics students ever since. I remember doing the experiment at a summer science camp while still in high school, and I was enthralled. At the time, I didn’t know why, but I do now. In many physics experiments, the results are not observations, but readings. You get a number from a dial, and if it is the right number, your experiment was successful. It is not very satisfying, as you are several frames removed from the actual phenomenon you are studying. But with the oil-drop experiment, you look through the eyepiece and find a drop, and then you carefully rotate the voltage control and watch as the drop slows down, stops, and begins to inch back up. A final tweak leaves it hovering in the air. It is almost like landing the Eagle on the lunar surface. Granted, you do then have to read some dials and do some calculations. But you still feel as if you captured those electrons alive and read their charges right off their backs.

Back In 1982, two New York Times reporters published a book, Betrayers of the Truth, in which Millikan (among others) was accused of scientific misconduct, because he supposedly "cooked" his data by selecting only the oil-drop measurements that would give a consistent result. Subsequent studies by historians of modern physics have pretty much vindicated Millikan; he did eliminate a number of his measurements from his final calculations, but for good reason, since they were uncertain, and even if you put all the data back in, you still get a figure for the electron charge that is within 0.2 percent of the correct value.

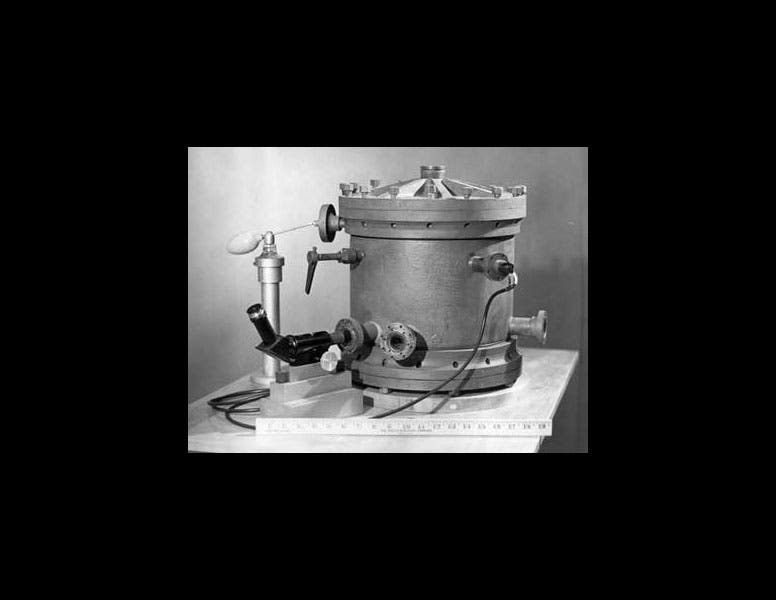

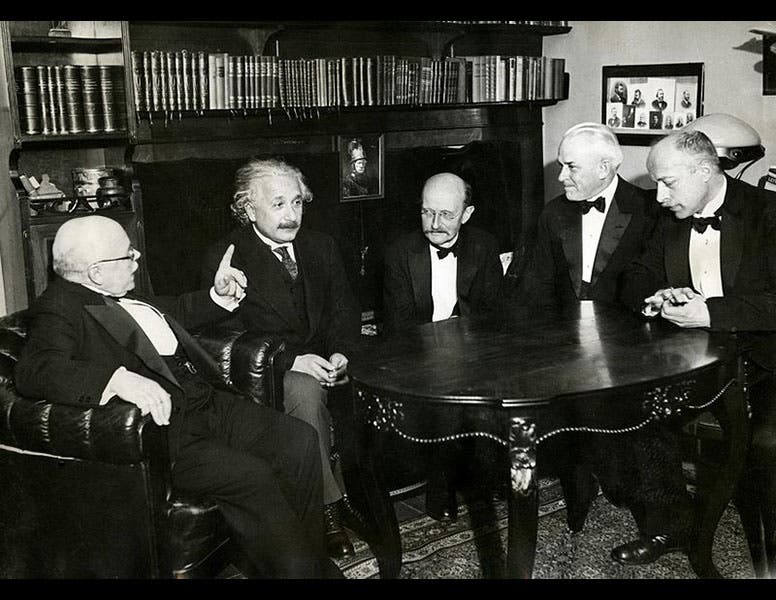

When you win a Nobel Prize, you get to hob-nob. The famous photograph above (third image) shows five Nobel Prize winners; from the left, they are: Walter Nernst, Albert Einstein, Max Planck, Millikan, and Max von Laue.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.