Scientist of the Day - Robert McCormick

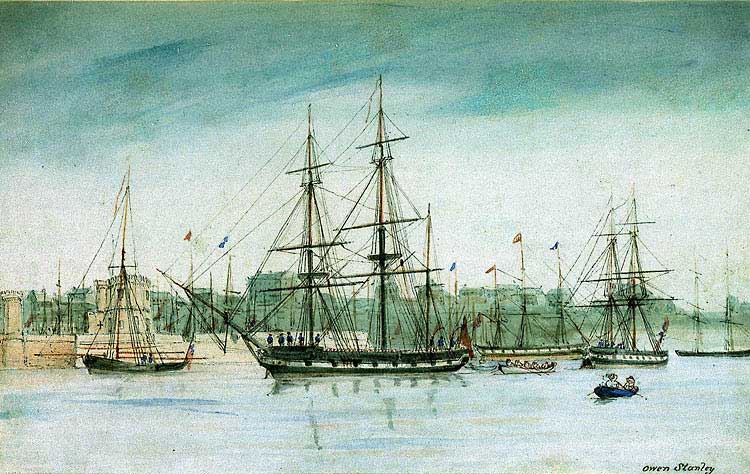

Robert McCormick, a surgeon in the British Royal Navy, was born July 22, 1800. McCormick's career had a promising start; he trained at Guy’s Hospital and St Thomas’s Hospital in London, and then accompanied Edward Parry on his 4th and last Arctic voyage in 1827, an attempt to sail to the North Pole from Spitsbergen. McCormick also studied natural history under Robert Jameson at Edinburgh, since ship's surgeons by tradition were supposed to be naturalists as well. This apparently qualified him for a promising appointment in 1831 – ship’s surgeon and naturalist on HMS Beagle (second image), which was off to South America for an extensive surveying expedition. What McCormick did not know (or perhaps did know and dismissed as inconsequential) was that Captain Robert Fitzroy had invited a gentleman on board to share his cabin and mess table, a young man by the name of Charles Darwin, fresh out of Cambridge, and McCormick's junior by 9 years.

Many people assume that Darwin was taken onboard as the Beagle's naturalist, but he was not. He was a super-numerary, a paying passenger, brought on board for his conversational skills. McCormick was the ship’s naturalist. Unfortunately for McCormick, young Charles, inexperienced though he was, proved to be a much better naturalist than McCormick. In a way, it wasn't a fair competition – Darwin brought along all sorts of instruments, such as microscopes, dissecting tools, specimen jars and labels, all paid for by his father, and of course Darwin didn't have to interrupt his pursuits to set bones and care for sick sailors. And he was enthusiastic in his collecting and exuberant about his discoveries. Fitzroy liked Darwin and would take him ashore to explore, leaving McCormick behind. McCormick did not take this at all well, and they had not been in South America very long when McCormick abruptly quit and sailed back home. In the vernacular of the Royal Navy, he was "invalided out." Now Darwin was the ship's naturalist, and we must say, he acquitted himself rather well, as McCormick had not.

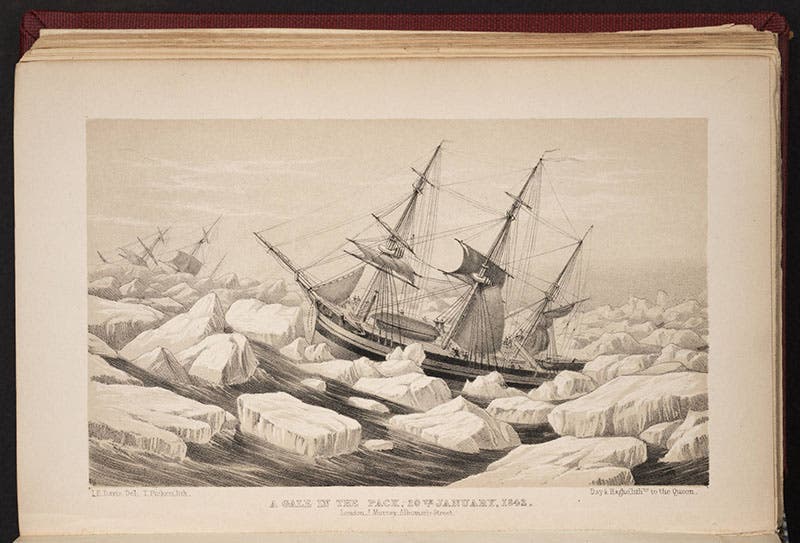

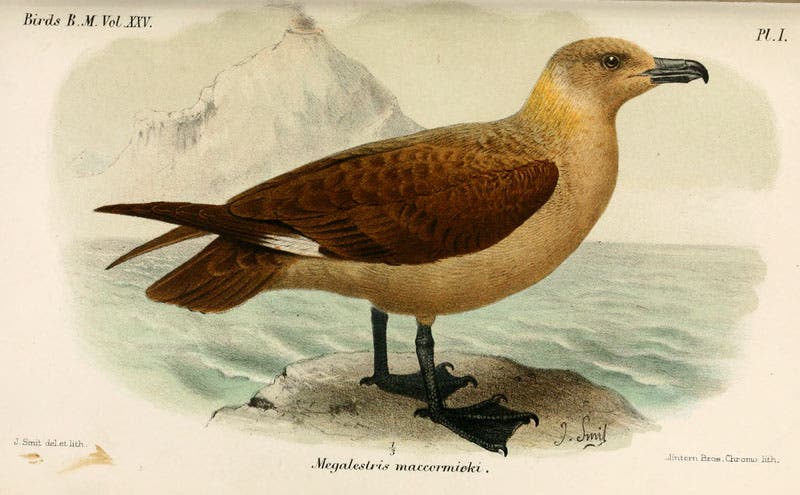

For reasons not clear, McCormick got another assignment – another plum assignment – when he was appointed surgeon-naturalist on board HMS Erebus, which was headed in 1839 to Antarctica along with HMS Terror (third image), both under the command of James Clark Ross. As was typical, McCormick had an assistant surgeon, a young man headed out on his first voyage, named Joseph Dalton Hooker. Hooker would, upon his return, become the most respected botanist in England, so this could have been the Beagle experience all over again, but luckily for McCormick, Hooker stuck to collecting plants, and McCormick had no competition for his principal passion, which was shooting birds. When they returned, Hooker published a massive 6-volume work, The Botany of the Antarctic Voyage of H.M. Discovery Ships Erebus and Terror, which became a milestone work on the plants of the southern hemisphere. McCormick published nothing. The sole tangible product of his participation was a new bird, a skua that he shot in Antarctica. It is called the South Polar Skua, or, in Linnaean terms, Catharacta maccormicki. Like other skuas, it is a noisy, distasteful scavenger, not a totally inappropriate bird to be McCormick's namesake (fourth image).

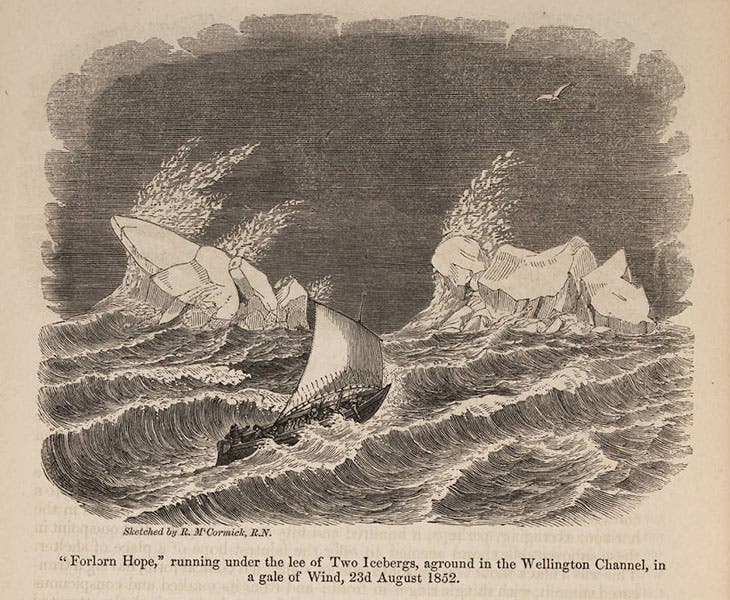

McCormick went on one other voyage, when he sailed with Edward Belcher's Arctic Squadron in 1852 in a search for the lost Franklin expedition. He somehow convinced Belcher to allow him to conduct his own personal search for Franklin, for he was given command of a whaleboat, which he sailed up the coast of one of the islands in the Arctic Archipelago. What we find baffling about this mini-adventure is the name McCormick gave to his boat. He called it: Forlorn Hope. Who goes on a rescue mission and names his ship Forlorn Hope? McCormick was one odd duck. We exhibited his account of his search (which, like all the other Franklin searches, was indeed forlorn) in our 2009 exhibition, Ice: A Victorian Romance, which included a sketch of the Forlorn Hope on shore, drawn by McCormick himself. Here we show another drawing that we did not display then, also sketched by McCormick, of the Forlorn Hope at sea (fifth image).

We know of only one portrait of McCormick, but it is by the estimable Stephen Pearce, who did portraits of all the Royal Navy polar explorers, including Parry, Ross, and Belcher. Most of Pearce’s sitters are presented as dashing and handsome officers, but McCormick’s portrayal is distinctly darker, for whatever reason. It is in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)