Scientist of the Day - Robert Knox

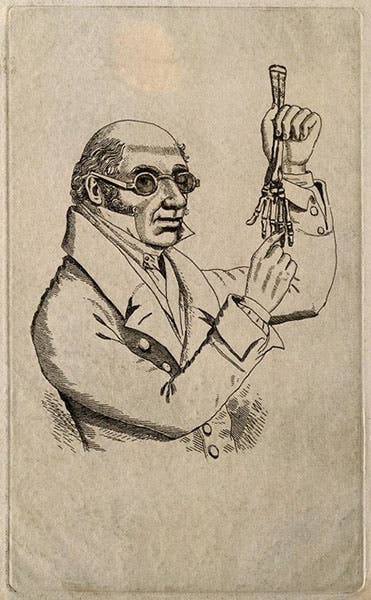

Robert Knox, a Scottish surgeon, died Dec. 20, 1862, at age 71. Knox was a private or extramural teacher of anatomy in Edinburgh in the 1820s. The medical college at the University of Edinburgh had a professor of anatomy, Alexander Monro tertius, but he was so inept – Charles Darwin found him "intolerably dull" and his habits disgusting – that students flocked to outside lecturers to learn the subject, and Knox was by far the most popular of these entrepreneurs. The Wellcome Collection in London has a handbill advertising Knox’s courses (second image), and is the source as well for our two portrait sketches. In his heyday, Knox had over 500 students paying to attend his lectures. Unfortunately, his heyday was cut short by the infamous Burke and Hare murders.

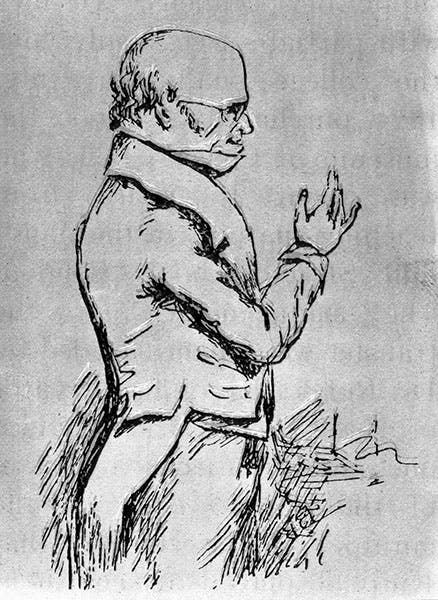

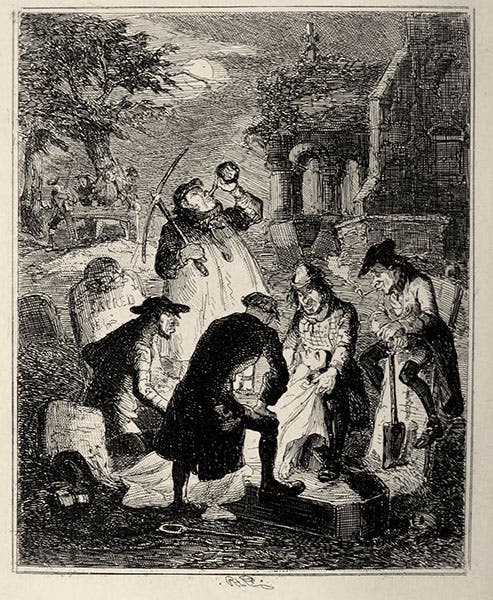

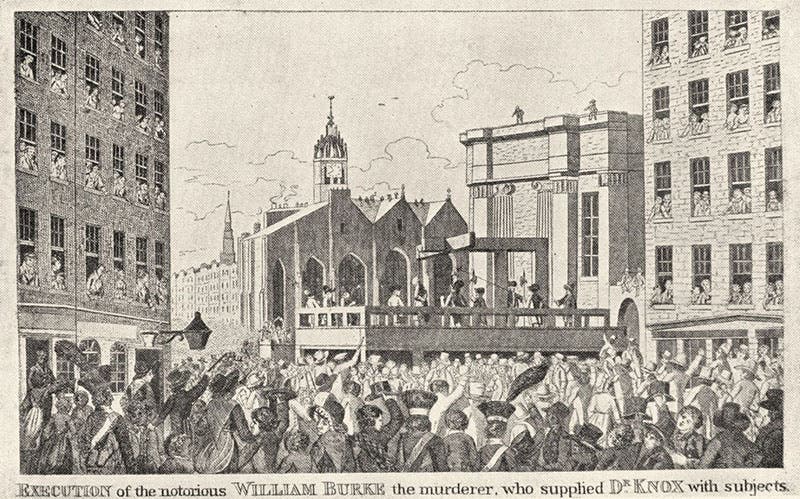

To teach anatomy properly, one needs bodies for dissection, and cadavers were always in short supply. Body-snatchers known as “resurrectionists” would surreptitiously remove corpses from graveyard coffins and sell them to the anatomy schools, but still, supply did not meet demand. We show a later Victorian cartoon about resurrectionists (fourth image). William Burke and William Hare, two laborers, met that need by creating their own cadavers. In little more than 12 months’ time in 1827-28, the pair murdered at least 16 victims whom they thought would not be missed, and sold the still-warm bodies to the unsuspecting Knox, who was happy to pay up to £10 each for the remains. Burke and Hare were finally found out; Hare turned state’s evidence, and Burke was hanged on Jan. 28, 1829, in a public spectacle (fifth image), after which his body, fittingly, was publicly dissected by Knox’s rival, Monro.

Knox claimed he did not know that his anatomy subjects had been murdered, and he was officially exonerated from any blame, but his reputation went south, and so, eventually, did Knox. As his student income plummeted, and as all his applications for official posts in Edinburgh were denied, he finally moved to London, where he eked out a living for the next 30 years as a popular writer and a pathologist. That is too bad, because historians now agree that his “philosophical anatomy” – his belief that anatomy is the key to understanding the laws of organic nature – was highly original, and had he been given the chance, he just might have joined the ranks of Georges Cuvier and Richard Owen as one of the premier anatomists of the age. Then again, he might have opened his mouth at the wrong time, as was his habit, and skewered himself again.

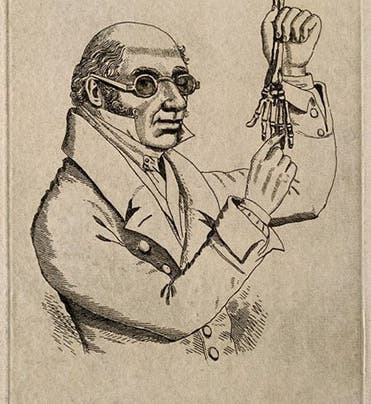

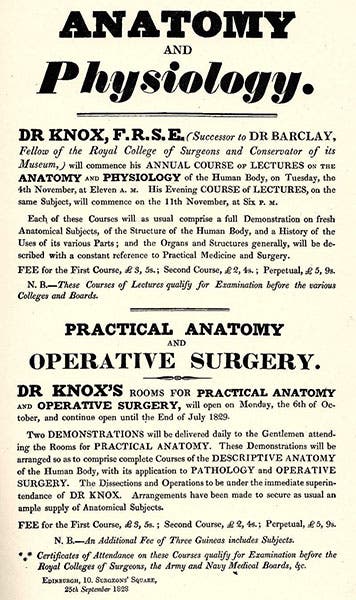

Knox was a formidable figure in the classroom. In addition to being a radical and an atheist, and continually fulminating against the university syndics and the town elders (much to the delight of his students), he was quite ugly, his face scarred by smallpox, which had also cost him his left eye. Perhaps in compensation, he dressed in a puce-colored waistcoat and wore jewelry while conducting dissections. We have several sketches of Knox; the first is the one most commonly reproduced, but we know not its draughtsman (first image). The second sketch, more sympathetic, was made by one of Knox’s most successful pupils, Edward Forbes, who later became professor of natural history at Edinburgh (third image).

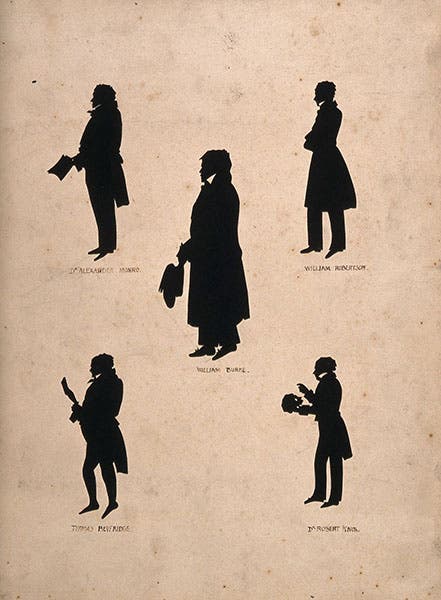

The Wellcome Collection, which owns a vast number of medical and anatomical ephemera, has a sheet with five cut-out silhouettes of individuals involved in the Burke and Hare scandal (sixth image). Two of the people depicted and labelled are obscure, but the other three were each notorious in their own way. The murderer, William Burke, is in the center; Alexander Monro, who dissected Burke after his execution, is at top left; and our subject, Robert Knox, is at bottom right, his puce waistcoat muted to black.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.