Scientist of the Day - Robert Kennicott

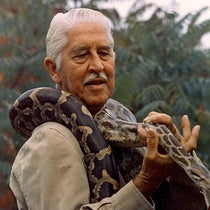

Robert Kennicott, an American naturalist and explorer, was born in New Orleans on Nov. 13, 1835 and grew up in Glenview, Illinois, near Chicago. His father, John, was a doctor and tree fancier who planted his many acres with new species of trees whenever he found them; the estate became known as "The Grove." Young Robert was a sickly child and could not be formally schooled, so he learned from his father and from the land he grew up on, becoming an ardent collector of naturalia in his teens. He seems to have sent specimens to Spencer Baird at the new Smithsonian Institution; at any rate, the two became correspondents and friends, and Kennicott continued to send Baird specimens.

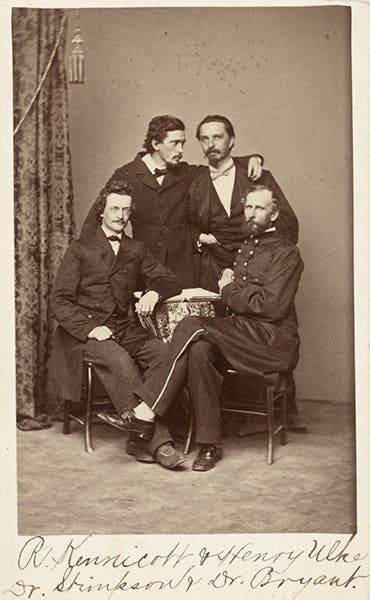

I do not know when Kennicott became formally associated with the Smithsonian. I think that an expedition he made in 1860 into the Mackenzie river basin in Canada was made under Smithsonian auspices. However, we know that by 1863, Kennicott was actually living in the Smithsonian "Castle," the Smithsonian’s first building. He was one of a number of young naturalists who worked for Baird and who called themselves the Megatherium Club. They all lived on the upper floors of the Castle, as did the Secretary, Joseph Henry, a much older man who was not so fond of the midnight shenanigans of the Megatherium Club. There is an often-reproduced portrait of four of the Megatheria; one print is in the Smithsonian Archives, another, the one we show here, is in the National Portrait Gallery (second image). We wrote a post on another Megatherium Club member, William Stimson, in 2022; you may see there a period photograph of the Castle, as well as the other print of the group portrait.

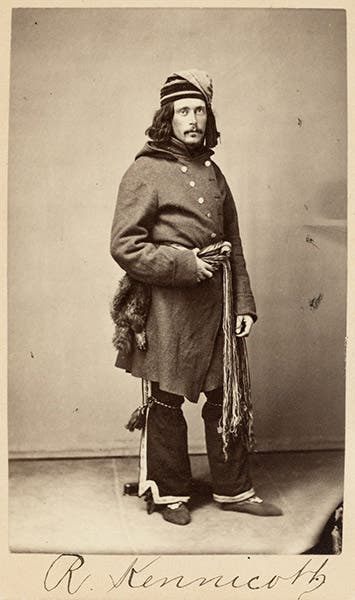

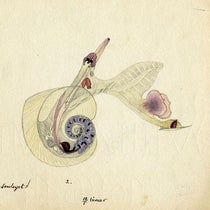

Kennicott was appointed in 1864 to the Western Union Telegraph Expedition, the mission of which was to survey a route for a telegraph line up into Alaska and ultimately across the Bering Strait into Russia. They started in San Francisco, moved north to Vancouver, and then up into Alaska. Kennicott collected and sent back specimens wherever he could find them; they included birds, snakes, and cultural items such as snowshoes and native clothing, many of which still survive in the Smithsonian collections. We show one here, of some Hare snowshoes from the Yukon (fourth image); you can see scores of others at this link to the Smithsonian archives.

And then one day, May 14, 1866, up on the Yukon river, Kennicott did not return to camp, and his friends found him in the field, dead at the age of 30. Noting that the vial of strychnine that he always carried (to kill small animals) was missing, some presumed his death was a suicide, although others doubted that this fun-loving adventurer would have taken his own life. The matter was unsettled until 1999, when his body, which had been taken back to the Grove and buried in the family plot, was exhumed and examined by a Smithsonian forensic team (no, not that of Temperance Brennan). They found small traces of various poisons in his body, about what you would expect in a naturalist who used substances like arsenic and strychnine in his taxidermic work, but far too little to be fatal. The cause of death was ascribed to a constitutional heart ailment, which also accounted for his childhood frailty, general weakness, and frequent bouts of fainting.

Since they had the exhumed skeleton at hand, someone decided to rebury Kennicott in full view of the public in a new Smithsonian exhibit in the National Museum of Natural History (fifth image). So if you look up Kennicott’s name on findagrave.com, you will find two entries; one for Glenview, Illinois, and one for Washington, D.C. The cenotaph for Kennicott can still be seen at the Grove, which incidentally is now a National Historic Landmark, but the body that used to be under it has gone east.

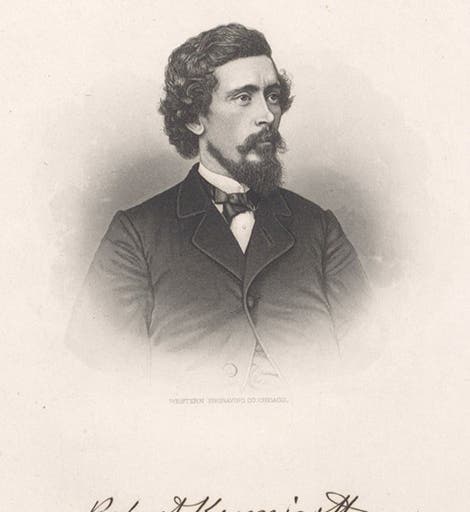

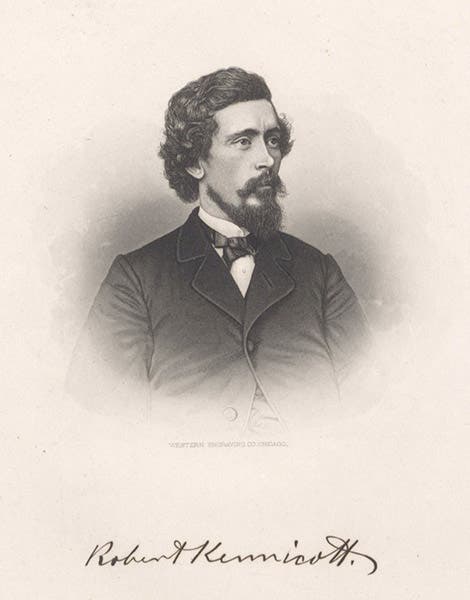

I can't remember how I discovered this, since it is not mentioned in any of the biographical articles, but extensive extracts from Kennicott's journals were published in the Transactions of the Chicago Academy of Sciences in their first volume, 1867-69. Kennicott had founded the Chicago Academy in 1856-7, before moving to the Smithsonian. We have vol. 1 in our serials collection, and we show here details of two extracts, one describing some field mice burrows he discovered in Canada (sixth image), the other the making of a rubbaboo, where Kennicott’s sense of humor is evident (seventh image). The portrait that introduces the Transactions article was used for our first image; it was taken from a print in the Smithsonian archives, the source of our other portrait of Kennicott (third image).

A book on Kennicott was published in 2010: A Death Decoded: Robert Kennicott and the Alaska Telegraph: A Forensic Investigation, by S. S. Schlachtmeyer, which probably answers some of the questions we raised about Kennicott’s life, but the Library does not own a copy, nor do I. We are taking steps to acquire one; if I discover that any part of my account needs correcting, I will do so, with apologies.

Lots of things are named after Kennicott: the Kennicott River in Alaska, the Kennicott Glacier, and a variety of animals, such as the Western screech owl, Megascops kennicottii, which was named after Kennicott by the great ornithologist, Daniel Giraud Elliot. We chose this photogenic flyer to include as our final image.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.