Scientist of the Day - Robert Howlett

Robert Howlett, an English photographer, was born July 3, 1831. Howlett attended the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, when photography was first presented to the public, and he was hooked. By 1854, he had teamed up with Joseph Cundall in London, specializing in studio shots, which was what most photographers did. In 1856, the two were commissioned by Queen Victoria to photograph returning Crimean war veterans, as a way to shine a favorable light on a disaster of a war. We include one of those above (second image). When the UK issued some Crimean War commemorative postage stamps in 2004, they selected 6 Howlett and Cundall photos for the purpose, which you can see here.

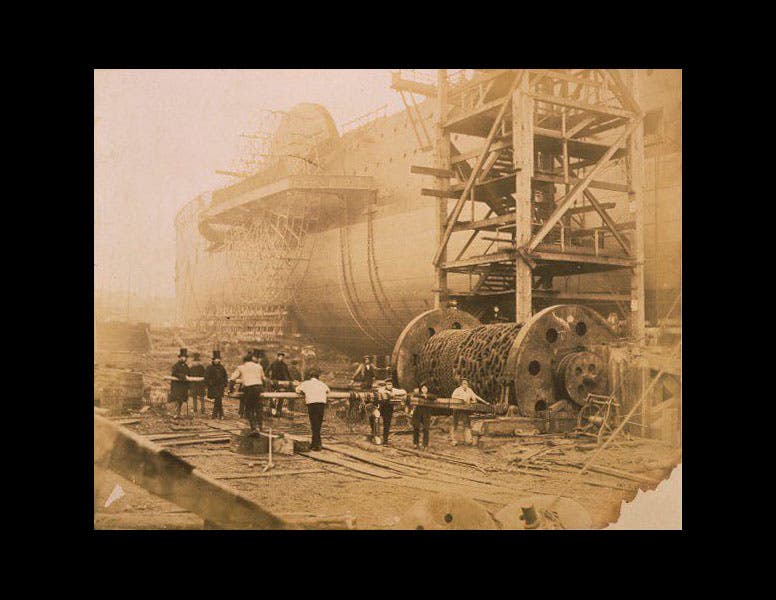

But it was in 1857 that Howlett, now working on his own, got the chance to show the real potential of photography, with a commission to photograph the completion of the building of the Great Eastern, the monstrous ship that would one day help lay the transatlantic cable. His documentary photographs of the ship construction, such as the first image above, are spectacular, but it was a photograph he took of the chief engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, that established his legacy (third image). There had never been a portrait like this, one that showed the subject in his element, here framed by those wonderful over-sized launching chains, and capturing Brunel's determination, grit, and independence, everything about him, right down to the mud on his boots and trousers. When we featured Brunel as Scientist of the Day several years ago, we led off with this portrait; indeed, it is impossible to talk about Brunel without showing it. Many historians of technology consider this to be the single most powerful portrait in the history of their discipline, and who can argue with that assessment.

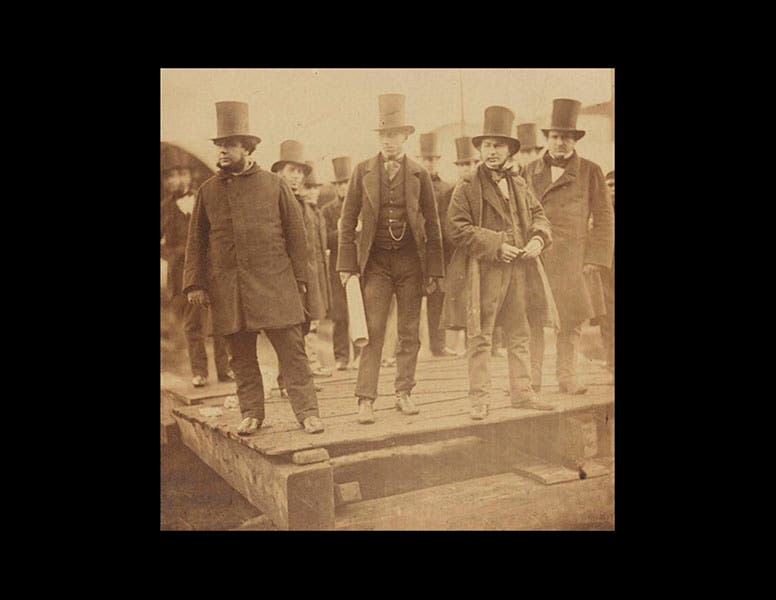

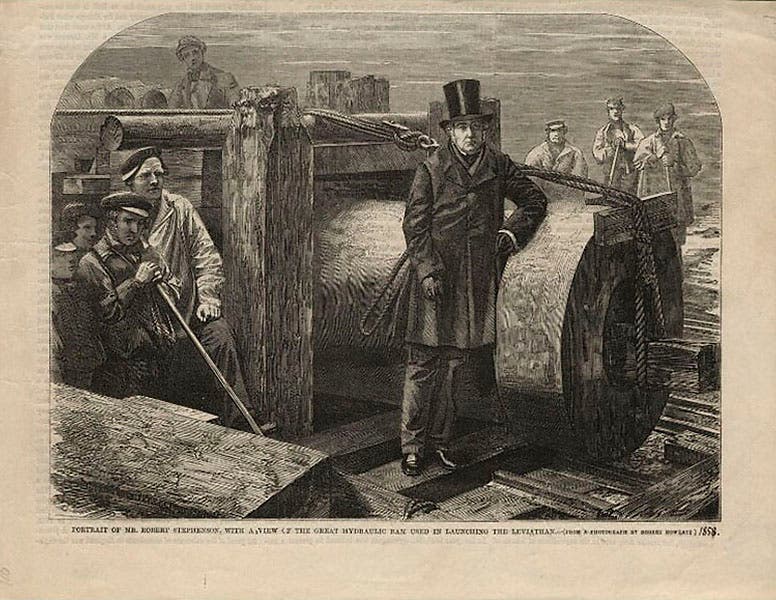

A close second might be Howlett’s photograph of Brunel and three others standing on a platform as the launch of the Great Eastern drew nigh (fourth image). Nothing further from a studio portrait can be imagined. There also survives a wood engraving of another engineer involved in the Great Eastern project, Robert Stephenson, based on a now-lost photograph taken by Howlett in 1858 (fifth image). Even though it lacks the rich tone of an original albumen print (such as the two photographs of Brunel), the wood engraving still retains some of the power of what must have been another gem of a photograph by Howlett.

Having brought photography into a new age, Howlett died, on Dec. 2, 1858, at the age of 27. Some think that Howlett was killed by the chemicals used in the wet collodion process, which Howlett adopted soon after its invention. Exposing plates under a hood with arsenic and mercury fumes present was probably not good for anyone’s health. But his death certificate states that he died of fever. It was a great loss to the infant discipline of portrait photography, but others, such as Julia Margaret Cameron, would soon show that Howlett’s invention of the photographic “eye” had not been in vain.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.