Scientist of the Day - Robert Hooke

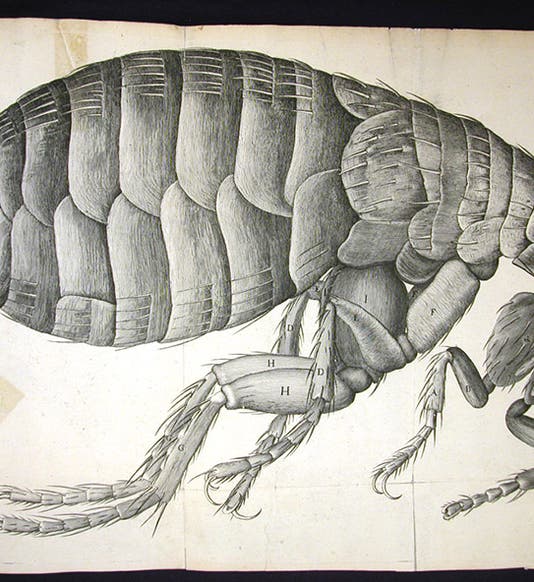

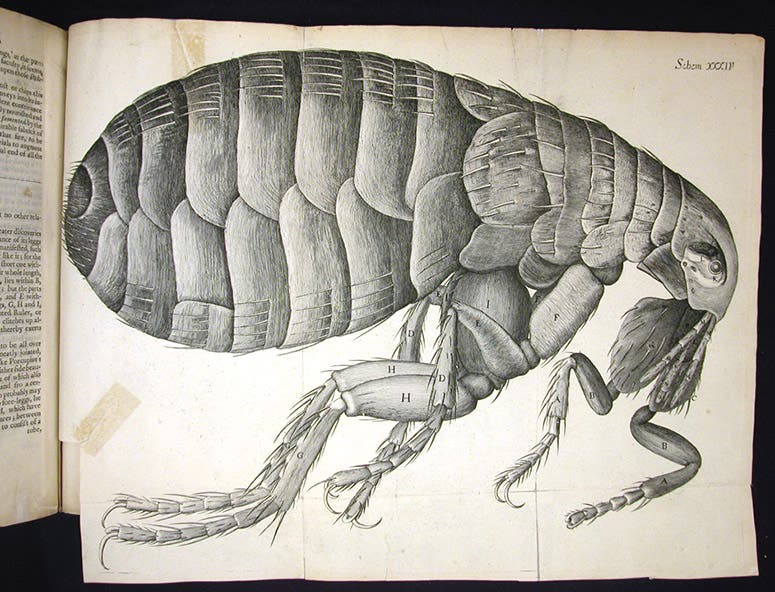

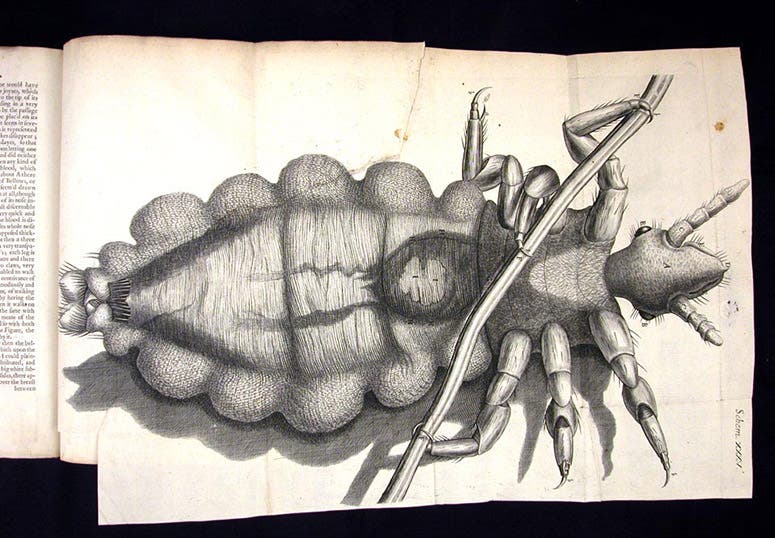

Flea, engraving, scheme 34, Robert Hooke, Micrographia, 1665 (Linda Hall Library)

Robert Hooke, an English mechanical artisan and natural philosopher, was born July 18, 1635, on the Isle of Wight. He came from a family of modest means, and when his father died, he took his £40 inheritance and moved to London, intending to study art, for which he had a natural talent. But he was persuaded instead to enroll in school, where he learned Latin and Greek and demonstrated a substantial native intelligence. He moved to Oxford, where he soon became the assistant of Robert Boyle, for whom he built the air pumps (vacuum pumps) used in Boyle’s pneumatic experiments, the results of which were published in 1660 and 1662.

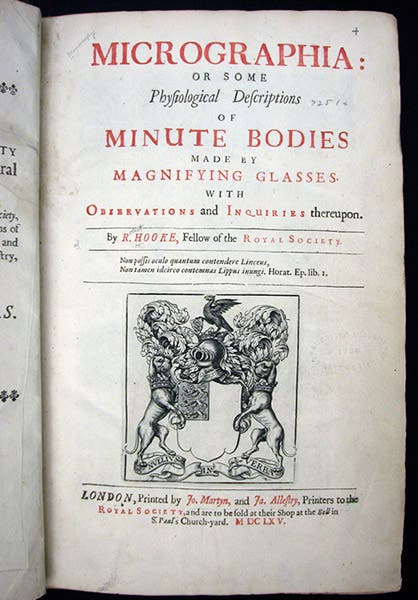

Title page, Robert Hooke, Micrographia, 1665 (Linda Hall Library)

With the Restoration of King Charles II in 1660, Boyle and Hooke moved to London, where Boyle was involved in helping to establish the Royal Society of London, chartered in 1662. Hooke was invited to organize and conduct experiments for the weekly meetings of the Society, for which he was paid a modest salary, the only paid position in the Society.

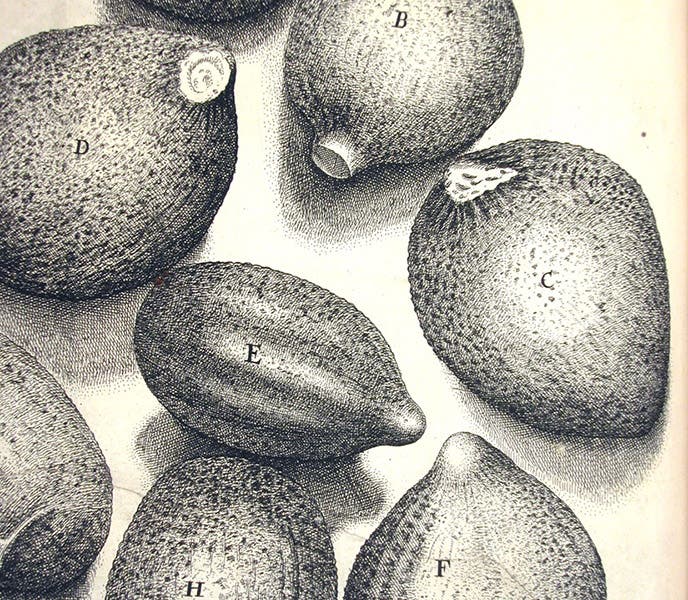

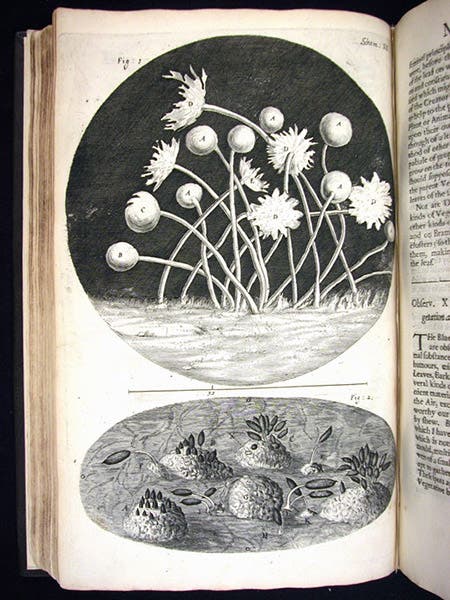

Thyme seeds, detail of engraving, scheme 18, Robert Hooke, Micrographia, 1665 (Linda Hall Library)

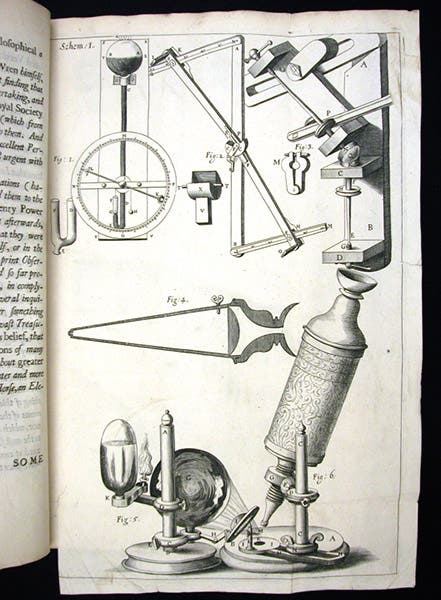

In 1663, Hooke began performing demonstrations with a microscope (that he had built himself, sixth image), which he continued for two years. In 1665, he published the results of these investigations as Micrographia, or some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies made by Magnifying Glasses, with Observations and Inquires thereupon. The volume was published under the auspices of the Royal Society, by their printers, with the coat of arms of the Society on the title page. It is one of the Royal Society’s first official publications, and it is the subject of our post today. We have a fine copy of the 1665 edition in our History of Science Collection

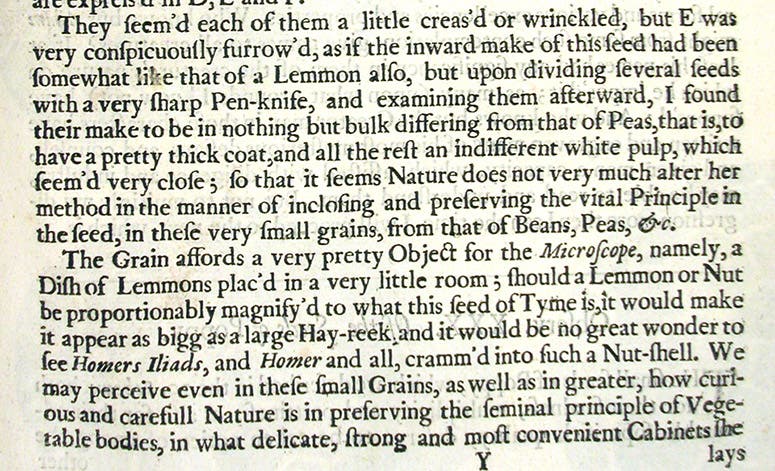

Text describing thyme seeds as a tiny bowl of lemons, Robert Hooke, Micrographia, 1665 (Linda Hall Library)

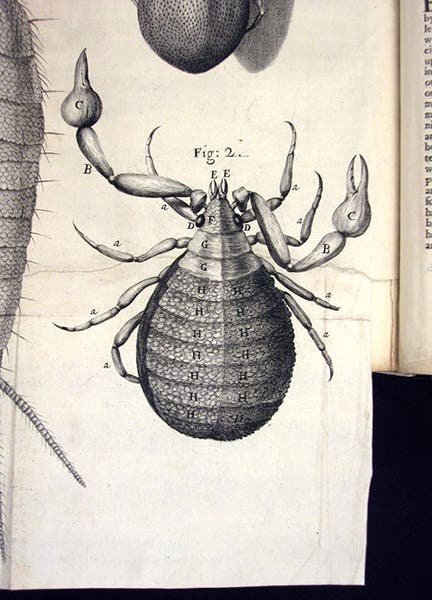

In the Micrographia, Hooke examined just about anything that would profit from magnification. He started with pins and razor blades, and moved on to seeds, fabrics, wood, mould, vinegar eels, and snail’s teeth, until finally focusing on insects, which occupy the last half of the book. The work is illustrated by 38 engraved plates, or “schemes,” as Hooke calls them, and the engravings, especially those of insects, are simply incredible. One must remember that, in 1665, no one had ever seen what a flea or a louse really looks like – fleas were jumping dots and lice were crawling specks. Insects were thought to be too small to have parts like circulatory and digestive systems. On plates that unfolded to 17” x 10” in size, Hooke revealed the complexity – and the alien nature – of the flea and the louse, with their jointed legs, and hairs, and complex mouthparts, to anyone who could bear to look (first and eighth images).

Tick, detail of engraving, scheme 33, Robert Hooke, Micrographia, 1665 (Linda Hall Library)

As impressive as the illustrations are, the text is equally impressive. Imbued as he was with the budding spirit of natural theology, Hooke gushed over everything that he saw. When he looked at thyme seeds with his microscope (third image), he commented that they appear to be a tiny bowl of lemons, and he even individuated them – this one is more like a lime, that one has a bit of stem attached, this other one is wrinkled (fourth image).

Robert Hooke’s compound microscope, engraving, scheme 1, in his Micrographia, 1665 (Linda Hall Library)

As he began his account of a tick, he related that he was reading a book, when the little fellow crawled over the edge of the book, and he immediately jumped for his microscope (fifth image). He found his tiny speck of blue mould (seventh image), which he called a “very pretty shap’d Vegetative body,” on the red sheepskin binding of another book, which prompted Hooke to remark that sheepskin seems more apt to gather mould than other leathers. Everything he saw provided Hooke with a reason to chat, so if you like chatty books, you will never find a better one than the Micrographia. And if you get tired of reading, there are always those beautiful engravings.

Mould, engraving, scheme 12, Robert Hooke, Micrographia, 1665 (Linda Hall Library)

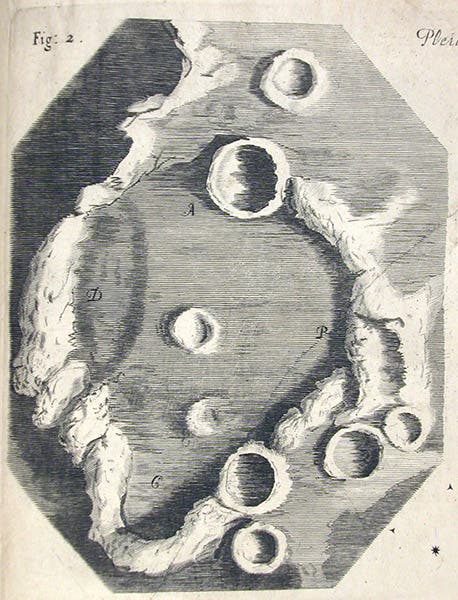

And I must mention a drawing that appears as a detail on the very last plate of the Micrographia, Scheme 38 (ninth image). It shows a crater of the Moon that we now call Hipparchus. It has nothing to do with microscopy, although everything to do with lenses. I don’t know why Hooke stuck it in at the end of his book, but the fact is that this is the first detailed drawing ever of any lunar crater, and it is surprisingly accurate, as you can affirm by comparing it to a modern photo of the region. It is such a remarkable illustration that we included it in our exhibition, The Face of the Moon, many years ago. No matter what Hooke did, he did it exceptionally well.

Louse, engraving, scheme 35, Robert Hooke, Micrographia, 1665 (Linda Hall Library)

When I used to give rare book room tours, I was often asked, what is my favorite book, and I would give different answers, depending on my mood at the time, but the Micrographia was frequently my choice. Hooke’s book was not as scientifically significant as say Kepler’s Astronomia nova or Newton’s Principia or Harvey’s De motu cordis. But it was a much more astounding book than any of these. It opened up an entirely new realm to the world – a world that until then had only a macrocosm – the cosmos – and a microcosm – the human-sized world – to deal with. Now there was a third domain, that of the very small, and no one was at all prepared for that. If ever there were a watershed book in this history of science, this was it.

The lunar crater Gassendi, detail of engraving, scheme 38, Robert Hooke, Micrographia, 1665 (Linda Hall Library)

Hooke was far from done when he finished his microscopic studies. In an earlier post, we discussed his realization that fossils are the remains of formerly living organisms, and his understanding that we can use these fossils to write a history of the Earth. He was also a gifted architect and helped rebuild London after the Great Fire. And he discovered that gravitational attraction is an inverse square force, which would lead to a priority dispute with Newton that would last until Hooke’s death in 1703. A third post on Hooke, focused on the controversy with Newton, would seem to be in order for some future date.

And if you are wondering why I have not included a portrait of Hooke, it is because there is no portrait. That is really unfortunate, when one thinks of all the forgettable figures of his day who did leave portraits behind. I regret the absence of a Hooke portrait every time I talk or write about him. He does not seem complete as a historical figure without one.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.