Scientist of the Day - Robert Grant

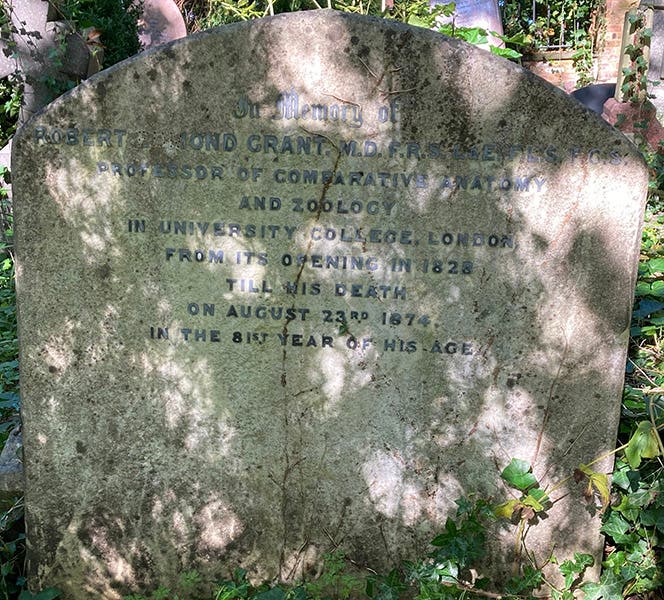

Robert Edmond Grant, a Scottish anatomist and invertebrate zoologist, died Aug. 23, 1874, at the age of 80. Grant became an "extramural" lecturer in anatomy in Edinburgh in 1824, meaning that he offered classes outside of the university curriculum, which medical students could attend if they paid the fee. Extramural lecturers in anatomy were popular at the time because the university professor, Alexander Munro III, was extremely disagreeable to students. Before teaching in Edinburgh, Grant had spent some time in Paris, and had met Georges Cuvier and Etienne Geoffroy Saint-HiIaire, who was what would later be called a "philosophical anatomist," meaning he was interested in the great plan of nature as revealed in the organization of the animal and plant kingdoms. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (unlike Cuvier) was also sympathetic to the evolutionary ideas of Jean Baptiste Lamarck. Many of these radical French ideas showed up in Grant's anatomy courses.

Grant was one of the more prominent faulty members of the Plinian Society at Edinburgh, a graduate student natural history club, and it was at one of the Society’s meetings that he met a 17-year-old second-year medical student by the name of Charles Darwin. The two apparently hit it off, for they were soon making trips together to investigate the tidal life of the Firth of Forth, not too far from Edinburgh, where Grant owned a house. Grant was one of the pioneering students of sponges (he gave them the name porifers) and other simple invertebrates, and he published a bevy of papers in the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal in 1826 and 1827. He showed Darwin how to gather these organisms, and how to use a microscope to study their behavior and means of reproduction. Darwin learned skills that he would never forget, and it is probably because of Grant that Darwin spent 8 years studying barnacles in the late 1840s.

It was also from Grant that Darwin first learned about the evolutionary theories of Lamarck, since Grant was an avid evolutionist, one of the very few in Edinburgh at the time. Darwin famously said in his Autobiography that this initial exposure to such ideas made no impression on his mind at the time, which seems belied by that fact that he clearly remembered the incident forty years later, when he wrote down his life story, and also because Darwin was quite familiar with the evolutionary ideas of his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin.

First page of article by Robert Grant, “Observations on the structure and nature of Flustrae,” Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, vol. 3, 1827 (Linda Hall Library)

One of the invertebrates that Grant studied was called Flustra, a strange colonial organism that resembles seaweed but is not related. It was sometimes known as a sea mat, and is now referred to as a bryozoan (second image). Darwin was fascinated with Flustra, and he soon discovered, with his microscope, that it reproduces sexually, and its eggs (ova) are ciliated, or free-swimming. He also found that the tiny black spots that one sometimes finds on bivalve shells are actually the free-swimming eggs of another invertebrate, a kind of sea leech called Pontobdella. Darwin was very proud of these discoveries and announced them at a meeting of the Plinian Society in 1827. He was quite surprised to learn that Grant had delivered a paper three days earlier to the Wernerian Natural History Society of Edinburgh and had announced the same discoveries as his own, without crediting Darwin (third image). It was Darwin's introduction to the strange world of professor-student publishing etiquette, and Darwin was not pleased about what Grant had done, and did not forget it. Relations with Grant were never the same after that.

Even before he gave his Flustra paper, Grant had accepted the offer to become Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy at the newly founded University of London (now University College London, or UCL), where he would teach until his death. It was quite a coup for Grant, and the future seemed bright for the 34-year old Scotsman. But things never quite panned out for Grant in London. The London professors were paid a very low salary, so they had to rely on student fees to survive, and thus spent nearly all of their time teaching. Grant couldn’t practice medicine in London because he was kept out of the Royal College of Physicians by his radical social and medical views. As a result, Grant lived in poverty for much of his London years and made very few other contributions to invertebrate zoology. In his Autobiography, Darwin expressed disappointment that Grant failed to distinguish himself after leaving Edinburgh. And that was unfortunate. Still, Grant did teach Darwin how to be a naturalist, and why invertebrates are important in the grand scheme of things, which he never would have learned at his next educational stop, the University of Cambridge. So if you are a fan of Darwin, you owe a thoughtful nod of appreciation to Grant.

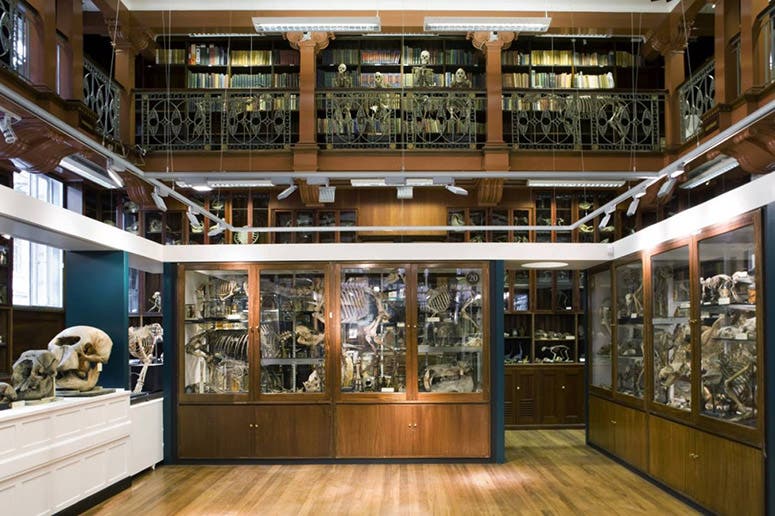

One of Grant’s lasting contributions to the University of London was to establish a zoological museum, no doubt recalling his time spent in the natural history museum in Edinburgh. He contributed many specimens and solicited donations from others, and he ran the Museum for 45 years. The museum survives, indeed thrives, and has been renamed, appropriately, the Grant Museum of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy. Not too long ago they moved to the former Medical School Library building at UCL, which provides sumptuous surroundings for such rarities as the only extant skeleton of the extinct quagga (which I think is the specimen on the balcony, to the right of the four skeletal librarians, in the photo, fourth image).

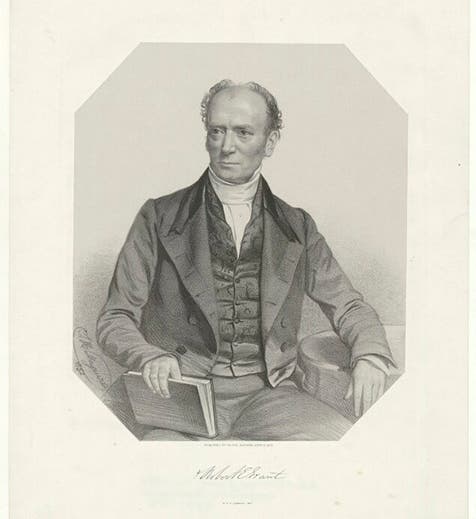

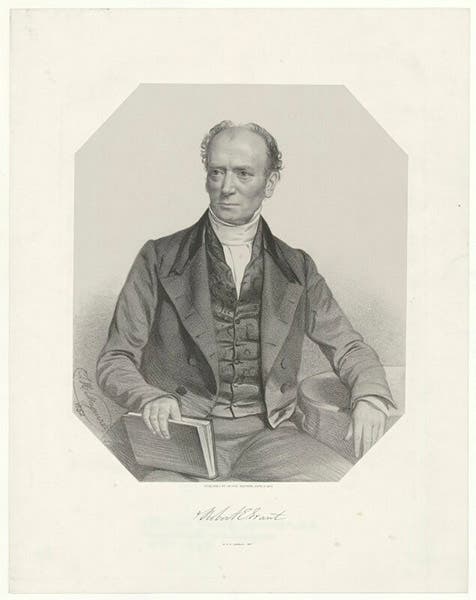

Grant was buried in Highgate Cemetery East, in north London (fifth image), where you may also find the graves of Marian Evans, better known as George Eliot, and Herbert Spencer. The excellent portrait of Grant by Thomas Maguire (first image) was one of a lengthy series that Maguire did of English scientists between 1849 and 1852. We have shown many of them in these posts, including those of Henry de la Beche, Joseph Dalton Hooker, and, of course, Charles Darwin.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.