Scientist of the Day - Robert Bakewell

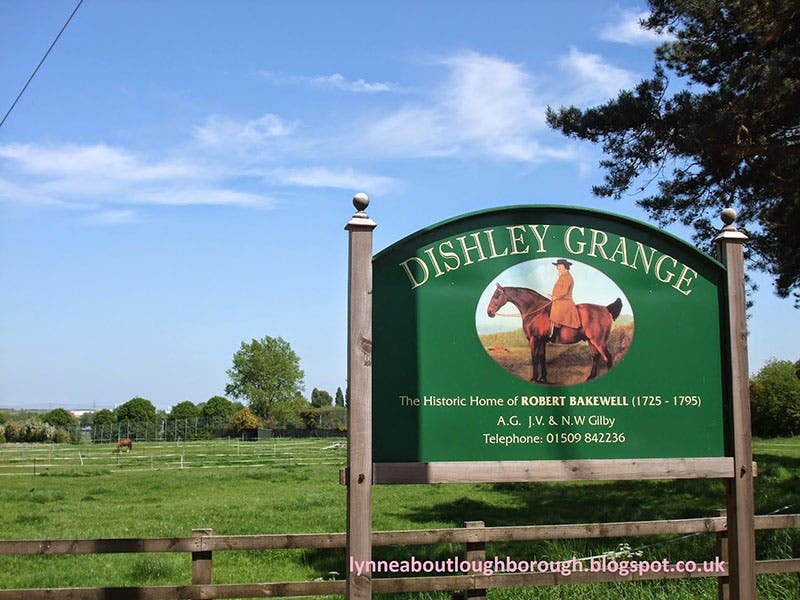

Robert Bakewell, an English farmer and animal breeder, died Oct. 1, 1795, at the age of 70. Bakewell, who lived at Dishley Grange in Leicestershire, in the English Midlands, has traditionally been considered one of the Big Five of the English Agricultural Revolution of the 18th century, along with "Turnip" Townshend, Arthur Young, Thomas Coke, and Jethro Tull. Bakewell made the list because of his pioneer work in producing new livestock breeds, especially the new Leicester sheep and the Dishley longhorn cow. The list has been under considerable attack in recent years – Jethro Tull, for example, has been crossed off many times, because he really made no difference in the progress of British agriculture, however memorable his name – and revisionists have similarly begun to target Bakewell. We will consider why, in a moment.

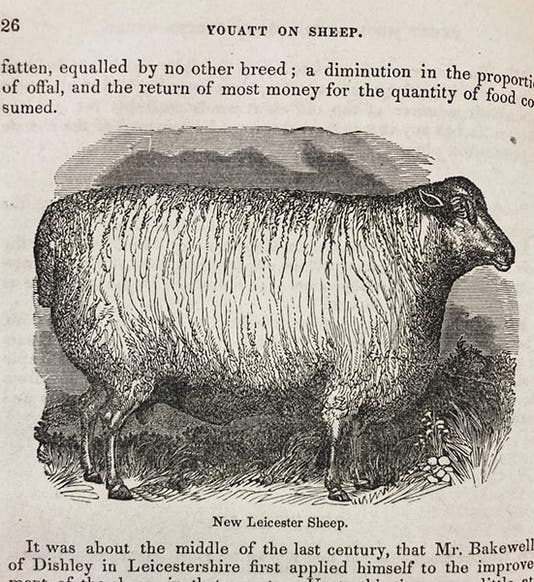

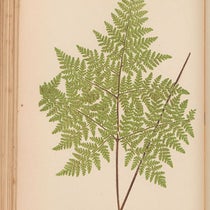

But first, we should discuss how and why Bakewell got on that list in the first place. Before Bakewell, sheep were bred primarily for their wool and secondarily for their food value. Leicester sheep were not especially meaty, and there was no systematic breeding process to improve either wool or meat production. At a time long before there was any understanding of genetics, Bakewell learned how to select rams and ewes for their desirable traits, with the result that his sheep slowly improved, with small bones and lots of mutton and fat. The new Leicester sheep, which he created on his farm, was twice the weight of the old Leicester breed. It had less wool, but farmers did not make money from the wool, they made it from the mutton.

Recent critics of Bakewell's place on the List have pointed out that Bakewell was not the only breeder in England who learned the importance of controlling which ram breeds with which ewes; others were improving their sheep with new breeding techniques. Bakewell, it is said, was just better at promoting himself and his sheep, and he was smart enough to charge more for tupping privileges with his rams than anyone else, implying that his stock was better.

However, if one consults books on sheep breeding a half-century after Bakewell, it is evident that Bakewell is the one who impressed breeders of the 1850s. We have a book in our collections, Sheep: Their Breeds, Management, and Diseases (1854), by William Youatt. Youatt has an entire section on the new Leicester sheep and he gives full credit to Bakewell. There is even a wood engraving of the breed, which we used for our first image. Everyone, relates Youatt, who visited Bakewell's farm was impressed by the size of his sheep, and by his Dishley longhorn bulls as well, which were twice as heavy as most bulls. Bakewell may not have been the only one in 18th-century England who was improving livestock by shrewd breeding. But he clearly was doing something right, and his contemporaries and successors were not shy about giving Bakewell the credit for the livestock-improvement part of the agricultural revolution.

They are certainly not giving up on Bakewell in modern-day Dishley Grange, where they have a welcome sign featuring Bakewell (fourth image) and a handsome historic plaque, recently installed (fifth image).

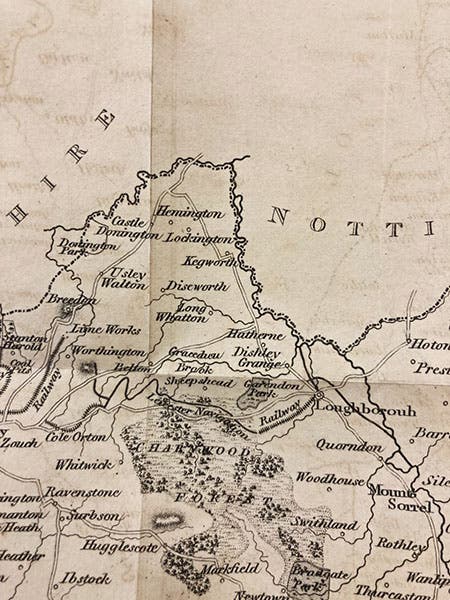

I thought I might mention, by way of conclusion, a historical resource that we have in the library that is under-utilized by historians of the English agricultural revolution. It is a set of 63 volumes, published between 1795 and 1817, most volumes of which have a title of the form: A General View of the Agriculture of the County of _____; fill in the name of an English or Irish county, and you have a volume in this Board of Agriculture series. The volume titled A General View of the Agriculture of the County of Leicester (1809), by William Pitt, has an entire chapter on sheep and a full discussion of the new Leicester breed. There is much here about Bakewell, not all of it complimentary, so Bakewell-bashing started early. One of the nicest features of these county histories is that most of them have a large foldout map of the county under discussion, and the volume on Leicester is no exception. We show you the full map, hardly any of which is readable at this scale (sixth image), and a detail of the area near the north-northwest border at about the 11:00 position, which includes Dishley Grange, next to the cusp of Nottinghamshire (third image). I wish the mapmaker had included a small new Leicester ram standing in the countryside, the way Renaissance cartographers used to include sloths and opossums in maps of Brazil, but such is not the case here, alas.

Bakewell’s equestrian portrait (second image) is in the National Portrait Gallery in London. As you can see, his sheep and his cattle are not the only things he fattened up during the course of his life.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.