Scientist of the Day - Richard Towneley

Richard Towneley, an English astronomer and natural philosopher, died at his home in Burnley, Lancashire, on Jan. 22, 1707. He was 77 years old, having been born in the family home at Towneley Hall on Oct. 10, 1629. The Towneley family had lived there since the 1400s, and would do so until the early 1900s (second image). They were Roman Catholics in a Protestant land and resolutely so, leading to their exclusion from much of society in Richard’s day, and forcing the Towneley’s to educate their children at Catholic schools on the continent. Richard found his social outlet in the pursuit of astronomy, instrument-making, and pneumatics.

Towneley is often referred to as a North Country astronomer, a label applied as well to three earlier scientific figures: William Crabtree and Jeremiah Horrocks, also from Lancashire, and William Gascoigne, from Yorkshire, all of whom worked between 1635 and 1642. Indeed, Richard’s father, Christopher, is largely responsible for preserving their papers, since none of them published much before their deaths at young ages. Without Christopher’s archival inclination, we would know hardly anything of the accomplishments of the North-Country astronomers. Nor would Richard have known what his fellow countrymen had been up to.

Most of the scientific activity in England in the 1660s was centered around the Royal Society of London, far removed from Lancashire. Richard gained access to that community through Henry Power, a physician of Halifax in west Yorkshire who had studied at Cambridge and came to know most of the founders of the Royal Society (in 1662), and himself became a fellow shortly thereafter. Power was a visitor to Towneley Hall, and arranged for Richard to visit London and meet Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke in 1661. Boyle was then working with his new air pump and about to discover Boyle’s law, when Towneley told him that he had discovered a relationship between the pressure and volume of an enclosed container of air, and Boyle later graciously referred to his law as “Mr Towneley’s hypothesis.”

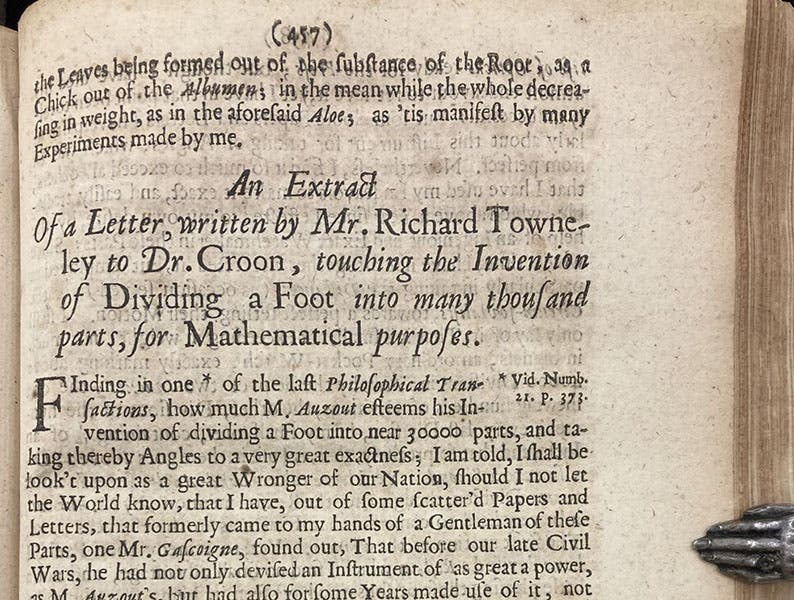

In 1667, Towneley, back at Towneley Hall, sent a letter to Hooke through a Dr. Croon, describing one of Gascoigne’s inventions, a micrometer that could be placed inside a Keplerian telescope that would allow one to measure the angular distance between any two objects, such as two stars. Hooke published the letter in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1667, and subsequently built and illustrated such a micrometer, following Gascoignes’/ Towneley’s instructions. We showed Hooke’s engraving and described the micrometer in more detail in our post on Gascoigne; here we show the first page of Towneley’s published letter, one of his very few publications (third image).

Jonas Mooe was another North Country mathematician and wealthy patron who moved to London and took part in the early activities of the Royal Society. It is thought that it was through Moore that Towneley met the young John Flamsteed, who would become the first Astronomer Royal of England in 1675. For Flamsteed, Towneley invented a new kind of clock escapement, called the deadbeat escapement. The escapement is the little oscillating device that regulates and powers a pendulum clock and enables it to beat exact seconds. The escapement then in use was an anchor escapement, which did a fine job, but had a little bounce-back with each swing of the pendulum, which caused a slight inaccuracy. The deadbeat escapement had no such recoil (fourth image). Jonas Mooe paid to have two pendulum clocks installed in the new Greenwich Observatory using Towneley’s deadbeat escapement. The clocks were built by Thomas Tompion. You can see the two clocks (sort of – they are somewhat hidden) in our post on Tompion. Later, in 1715, George Graham improved the deadbeat escapement, and his name is often associated with its invention, but for that, the credit indubitably should go to Towneley.

When he died in 1707, Towneley was buried in St. Peter's Churchyard in Burnley, but findagrave.com has no photos of a gravestone, and I could not find one elsewhere. Nor does there seem to be a portrait of Towneley. All we have is a modern sundial, with Towneley’s name engraved upon it, on a wall at Towneley Hall (first image). Fortunately, it is a handsome one, and will do quite nicely as a memorial.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Bivouac on Jan. 26 [1854], chromolithograph from a sketch by Balduin Möllhausen, Explorations and Surveys for a Railroad Route from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean: Route near the Thirty-Fifth Parallel, by Amiel W. Whipple (Pacific Railroad Report, 3), 1856 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/55140a90-4b5d-4dac-832c-5def5cb51a10/Whipple1_cover.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)