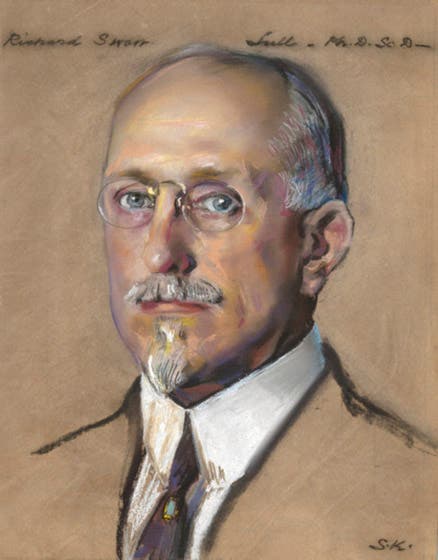

Scientist of the Day - Richard Swann Lull

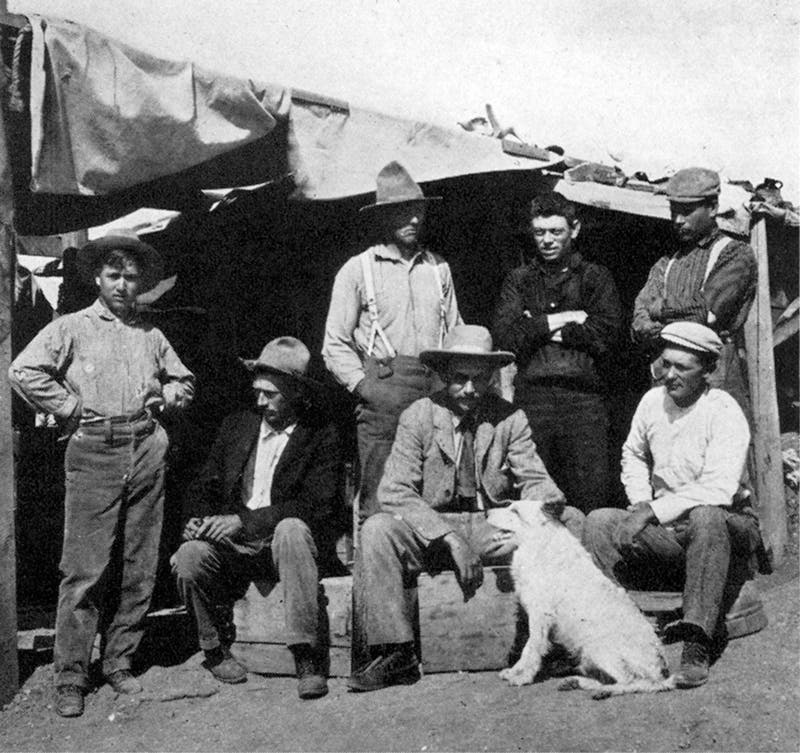

Richard Swann Lull, an American paleontologist, was born Nov. 6, 1867. Swann became interested in dinosaurs when he studied in Amherst, Mass., where Edward Hitchcock had assembled an impressive collection of Triassic dinosaur trackways. So when he was offered the opportunity to work on an expedition to recover a brontosaurus skeleton in Wyoming for the American Museum of Natural History in 1898, he took it. A well-known photograph shows the expedition staff on site - that is Henry Fairfield Osborn seated at center, with the dog, and Lull is standing just behind him, with the tall soft hat and white suspenders. Lull then studied under Osborn at Columbia University, received his PhD, and in 1906, took a dual job teaching at Yale College and curating at the Peabody Museum of Natural History. He would be a fixture at Yale until his death in 1957.

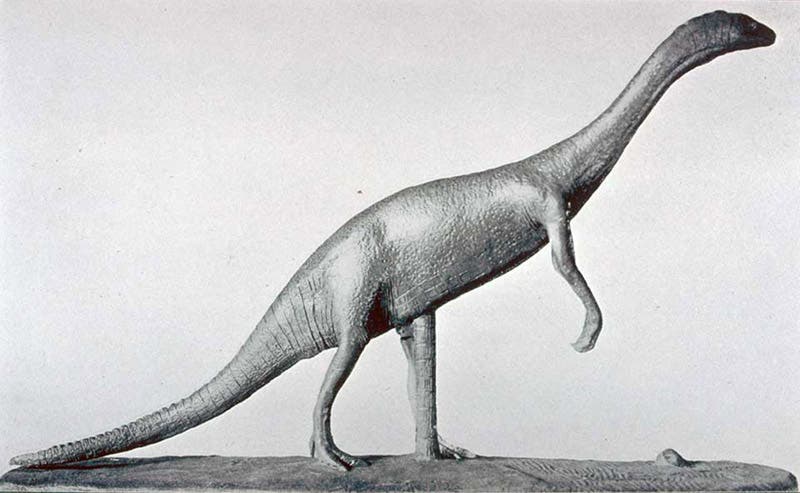

Perhaps because of his early exposure to Triassic trackways at Amherst, Lull took a special interest in the dinosaurs of the Triassic, even though they are less mind-boggling than the behemoths of the Jurassic such as Brontosaurus. Eventually. he published the definitive work on early Mesozoic reptiles, Triassic Life of the Connecticut Valley (1915), a monograph we have in our collections. One thing Lull seemed to be passionate about was the use of models in reconstructing dinosaurs, perhaps a result of working with Charles Knight at the American Museum, who loved to make models. Lull’s Triassic Life contains a photograph of a model he himself made of Anchisaurus, a smallish dinosaur named and described in 1893 by Othniel Charles Marsh, the man whom Lull succeeded at Yale. The model, which still survives, is interesting because one side shows the complete restored animal (third image), and the other side is cut away to reveal the skeleton inside (first image). Lull may have invented this kind of double-sided model, since to the best of my knowledge, Knight never made a model like this.

As it happens, the Peabody Museum at Yale contains a fragment of an Anchisaurus skeleton that predates, in its discovery, every other dinosaur fossil found in the United States, and all but one in England. It was blasted out of a well in East Windsor, Conn., by Solomon Ellsworth in 1818, a chunk of rock with visible embedded bones, and it ended up in the collections of Benjamin Silliman at Yale, long before there was a Peabody Museum. It is not clear to me, because I do not have access to either Marsh's paper or Lull's monograph right now, whether it was recognized at the time that the Ellsworth specimen was indeed an Anchisaurus, or if that recognition came later. If and when I can find out, I will update this post.

Many years ago, when we mounted our Paper Dinosaurs exhibition on the history of dinosaur discovery, we displayed Lull's 1915 monograph on the Triassic, where we showed the image of Anchisaurus that we show here (third image), as well as this one.

Should you have a yen to visit Yale and see the Peabody Museum’s superb collection of dinosaurs, be forewarned that the museum is closed until 2023, and the closure has nothing to do with the pandemic – rather, they are reconstructing their hall of dinosaurs. News releases promise that many of the dinosaurs will be remounted in accordance with modern views of dinosaur posture, which I find very sad and wrong-headed, as mounts like their Brontosaurus, the first ever discovered, are historic in their own right and should be left alone. There are plenty of other brontosaurs that are mounted "correctly". Marsh’s Brontosaurus should stand as he envisioned it.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.