Scientist of the Day - Richard Spruce

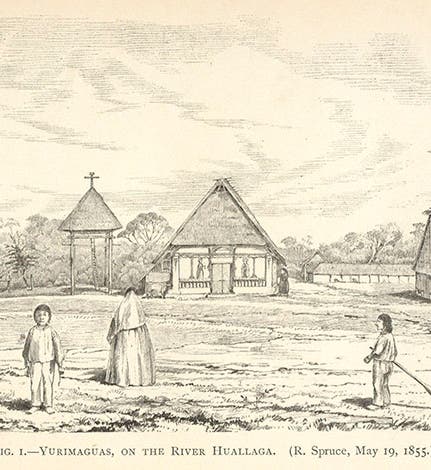

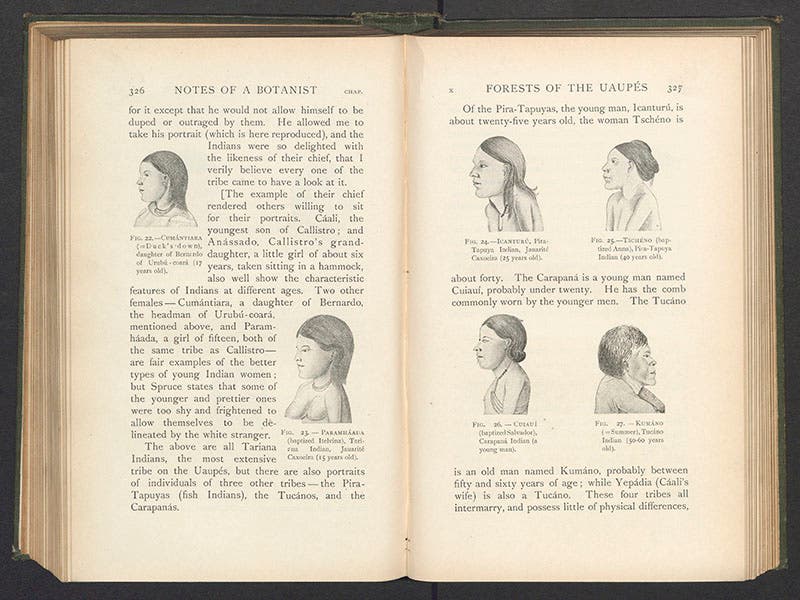

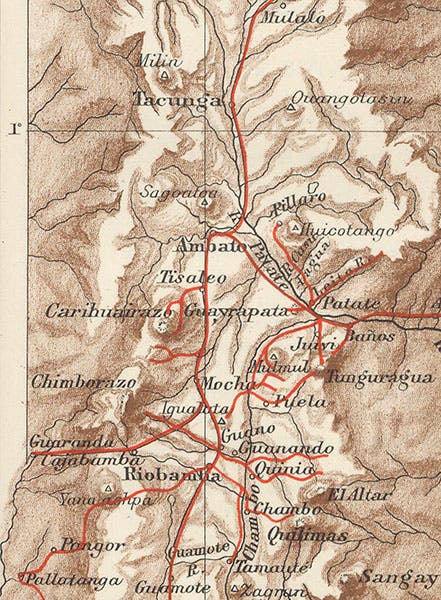

Richard Spruce, an English botanist and explorer, was born Sep 10, 1817. From an early age in Yorkshire, Spruce taught himself botany, acquiring a particular fascination for mosses and liverworts – studying what a modern botanist would call bryophytes. He impressed people such as William Hooker and George Bentham at Kew Gardens , who sent Spruce on a collecting expedition to the Pyrenees, and he did so well that his sponsors suggested that he travel to the Amazon basin to collect Brazilian plants, an enterprise that Spruce eagerly agreed to. He arrived in 1849 and met two fellow naturalists who had arrived a year earlier, Alfred Russel Wallace and Henry Walter Bates. Wallace would explore for just four years, Bates, for eleven, and Spruce for 15 years. During that time, he collected along the entire length of the Amazon River, including the Rio Negro and the Upper Orinoco rivers. Spruce eventually made it to Ecuador and the Andes. He took notes and wrote letters assiduously. A competent artist, he often made sketches of towns and villages and of native peoples that he encountered (first and third images).

Spruce’s health had always been poor, and in his first 10 years in South America, he suffered from a variety of tropical diseases, but in 1860, he came down with a painful semi-paralytic affliction that greatly hindered his movement and made it impossible to sit at a microscope, a considerable handicap to a bryologist. No one could diagnose the ailment, and it caused him debilitating pain for the rest of his life. Yet this disability hardly dampened his enthusiasm, and one would never know from his letters how much he suffered in his daily life.

In 1859, Spruce received a letter from Clements Markham, on behalf of the East India Company, requesting that he collect seeds and living specimens of red bark cinchona, Cinchona succirubra (now C. pubescens), a tree native to the equatorial Andes, that might be transported to England for planting and then exported to India. Cinchona red bark was the source of quinine, the only known drug that could relieve malarial fever. It grew naturally only in the Andes, and export of seeds and saplings was rigorously prohibited by the land barons of Ecuador. Spruce accepted the task, and with the assistance of a gardener sent by Markham from England (a wise move, since botanists often have few clues about gardening), they managed to collect some 100,000 seeds and grow some 600 sprouts that they smuggled back to Kew in late 1860, in Wardian cases that Markham had thoughtfully supplied. Soon cinchona trees were growing at Kew and then in India and Ceylon, and southeast Asians now had the same remedies for malaria that previously had been available only to affluent purchasers of the expensive Andean cinchona bark.

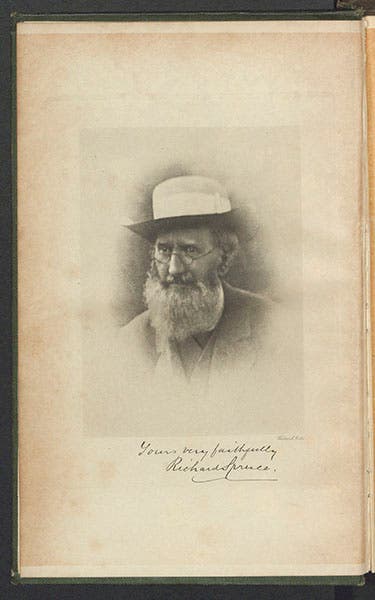

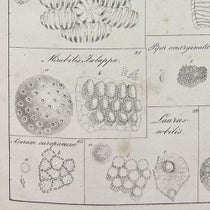

After Spruce returned to England in 1864, he eventually settled down in a cottage in his native Yorkshire, trying to write up his notes on liverworts, despite his continuing physical afflictions. That work was finally published in 1885, Hepaticae of the Amazon and Andes of Peru and Ecuador. It discusses over 500 liverwort species, most of which Spruce discovered and was the first to describe. Sadly, that work is lacking from our collections, although we have hopes of acquiring it. Spruce never published a descriptive account of his South American travels, as had both Wallace and Bates, but long after Spruce's death in 1893, in a wonderful show of lasting friendship, Wallace sat down with Spruce's large collection of notes, letters, and sketches, and fashioned from them a narrative: Notes of a Botanist on the Amazon & Andes, which he published under Spruce's name in two volumes in 1908, with a glowing biographical introduction (fourth image). For illustrations, Wallace used Spruce's drawings, as well as contemporary photographs and maps drawn from various sources, and we in turn have drawn on these for some of our images here. Wallace also included a portrait that is one of the two standard images of Spruce (second image).

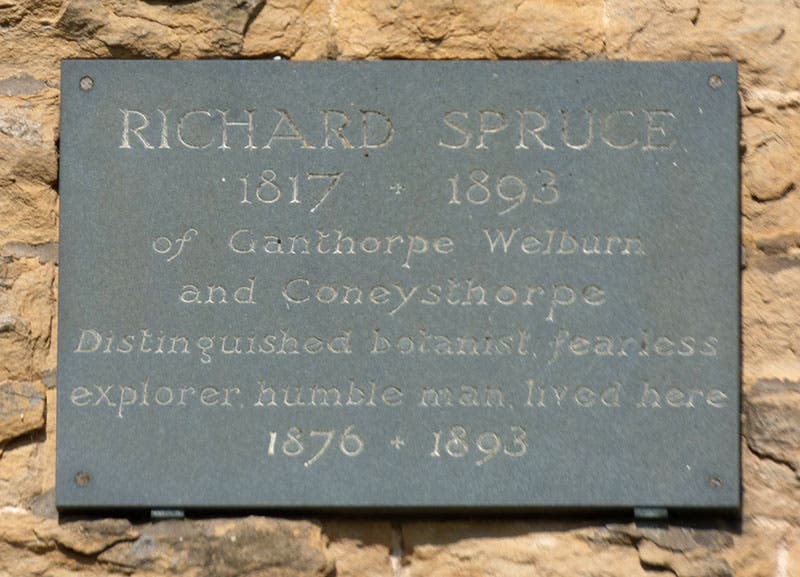

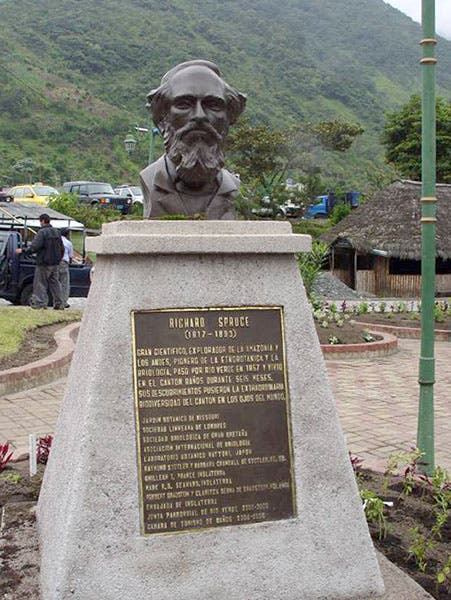

It is odd how little-known Spruce is today. Nearly all of my students have heard of Darwin, most of Wallace, some of Bates, but none has ever expressed a previous knowledge of Spruce. Yet he was the most dedicated explorer and by far the best botanist of them all, and in terms of his humanity and cheeriness in the face of debilitating pain, he was by all accounts the most wonderful of human beings, and deserves more public recognition than the tribute on his gravestone, the plaque on his Yorkshire cottage (sixth image), and a bust recently erected in Ecuador (seventh image), which is all there is for Spruce monuments. A full-blown statue, perhaps at Kew Gardens, would be a nice start.

In 1873, Richard Spruce wrote a letter about the attractions of hepatica to Daniel Hanbury (a close friend who would die unexpectedly in 1875), which Wallace included in his introduction in 1908. It is well known to bryologists but to hardly anyone else, so it seems worth quoting here:

I like to look on plants as sentient beings, which live and enjoy their lives – which beautify the earth during life, and after death may adorn my herbarium … . It is true that the Hepaticae have hardly as yet yielded any substance to man capable of stupefying him, or of forcing his stomach to empty its contents, nor are they good for food; but if man cannot torture them to his uses or abuses, they are infinitely useful where God has placed them, as I hope to live to show; and they are, at the least, useful to, and beautiful in, themselves – surely the primary motive for every individual existence.

Elaine Ayers, at New York University, wrote an very nice online article about Spruce’s passion for mosses and liverworts that appeared a few years ago in Public Domain Review; you may access it here. Professor Ayers illustrated her paper with two stunning plates from Ernst Haeckel’s Kunstformen der Natur (1904), depicting mosses and liverworts, in case you were wondering what bryophytes actually look like.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.