Scientist of the Day - Richard Roberts

Richard Roberts, a Welsh mechanical engineer, toolmaker, and inventor, was born in Llanymynech, Powys, on Apr. 22, 1789, and died on this date, Mar. 11, 1864. His father made shoes and also collected tolls from New Bridge traffic. Their house sat exactly on the border – go out the front door, you were in Wales; out the back door, in England. How cool would that have been for a young lad?

Roberts learned various skills growing up, including patternmaking and turning, and worked at both trades in Manchester and Salton. He spent a year or two at Henry Maudslay's shop in London, where he learned the value of precision engineering.

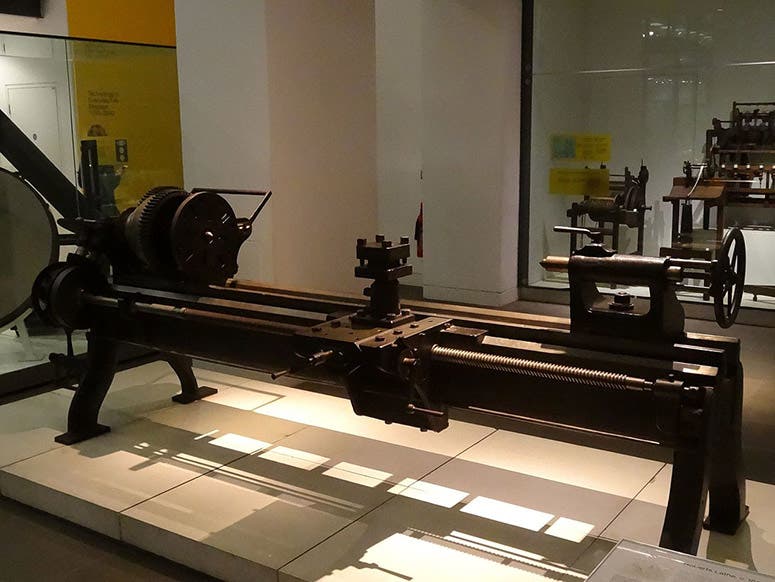

Roberts built a slide-rest lathe in 1817 that is considered so excellent that it is on display in the Science Museum, London, along with one of Maudslay's lathes. Roberts also built a metal-planing machine and a variety of drilling machines. But his big invention came when he had moved back to Manchester – the self-acting spinning mule, patented in 1825, and then again, improved, in 1830.

Changes in textile making were at the heart of the Industrial Revolution. In 1700, cloth began with yarn that was spun on a single hand-operated spinning wheel, and then woven on a hand loom. By 1800, much of that process had been automated. The last significant invention was the spinning mule, built by Samuel Crompton in 1779, which spun fiber (called roving before it was spun) into thread with a water-powered machine. It was mostly automatic, but not quite, requiring constant supervision, and the help of young boys, called piercers.

Roberts completed the automation process for making thread, adding complex mechanisms for regulating the tension on the roving and the thread, and the speed of the rollers that twisted the roving, and the winding onto spindles – hundreds of spindles at once. The most dramatic part of the self-acting mule is the traveling carriage, which can be over 100 feet long, moving back slowly about 5 feet to draw the roving through the rotating cylinders, and then forward to wind the thread onto the spindles (first image). A complex system of wires raises and lowers the threads at the right time, as you can see in this video of a later self-acting mule in operation.

Roberts also invented a power loom built entirely of cast iron (most looms then were made of wood), and sold thousands of these to textile factories all over the British Isles.

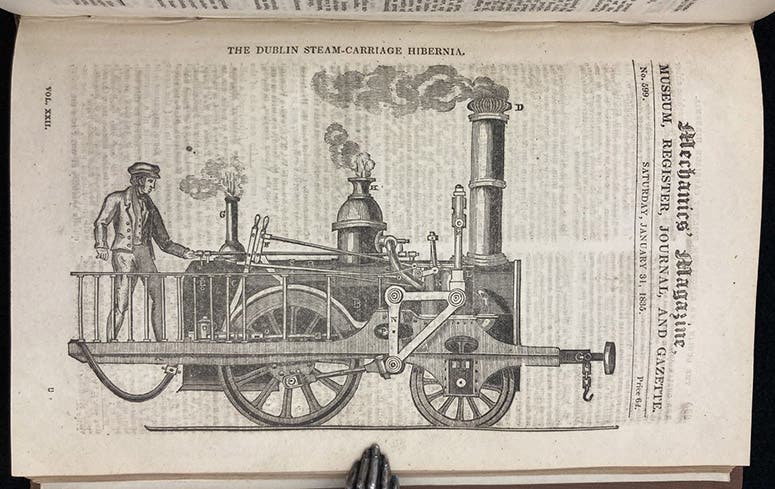

Roberts organized a company around 1826, Sharp, Roberts, and Co., whose growth coincided with the explosion of railroads onto the British landscape and the sudden need for locomotives. Roberts designed several, including the Hibernia, built in 1834 for the Dublin and Kingstown Railway, which was featured in Mechanics' Magazine in January 1835 (fourth image).

Roberts continued to invent and manufacture machinery, many of them precision machines, for two more decades. One was an automatic iron punch, controlled by Jacquard cards. Edwin Clark was trying to construct an iron tube bridge over the Conwy River to Conwy Castle, and the men who were hand punching the rivet holes were doing a terrible job, so that holes did not line up properly. Roberts supposedly produced his automatic punch after Clark cried out for help. I could not find a image of Roberts' punch engine, but you can see some of the riveted tubes at our post on Clark.

Roberts never made much money from his inventiveness, since he failed to patent many of his later inventions, because of the expense of defending them, and as a result, he died in poverty. But somebody found the means to bury Roberts in Kensal Green Cemetery in London, where he shares the soil with many great engineers, including, Marc Brunel, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and Charles Babbage.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.