Scientist of the Day - Richard Harlan

Richard Harlan, an American naturalist, was born Sep. 19, 1796. Harlan wrote the first book about North American mammals, Fauna Americana (1825), and because of that, and the fact that he worked within the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, people sent him things, bizarre animals and perplexing fossils. One specimen came to him from South America in 1824, and it looked like the offspring of a tiny armadillo and a large rodent. Harlan called it Chlamyphorus and published a description and an engraving in the first volume of the Annals of the Lyceum of Natural History of New York. It is in fact the first description of an Argentinian pink fairy armadillo (first image). It still carries Harlan's generic name, and the specific name, truncatus, which in this case means "sawed-off" and seems a perfectly appropriate descriptor.

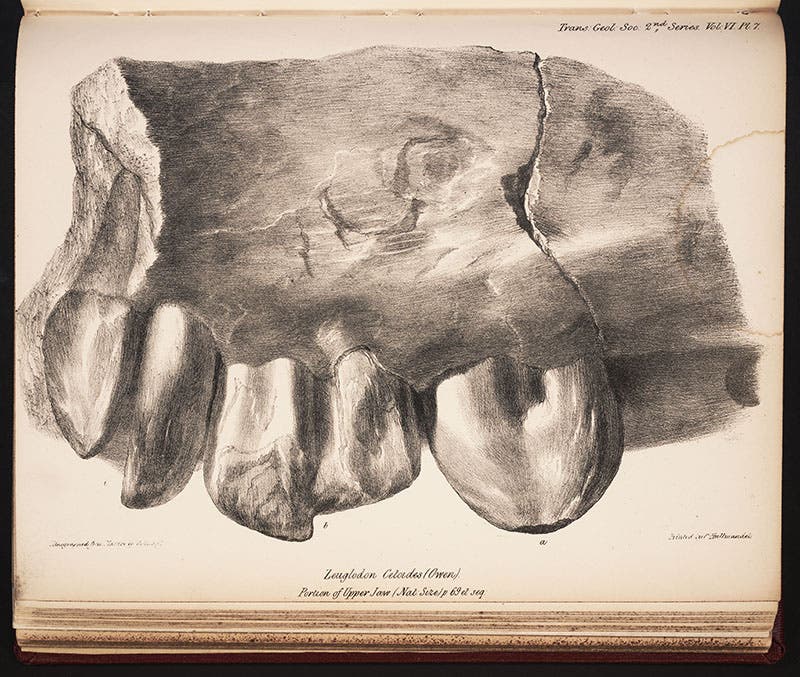

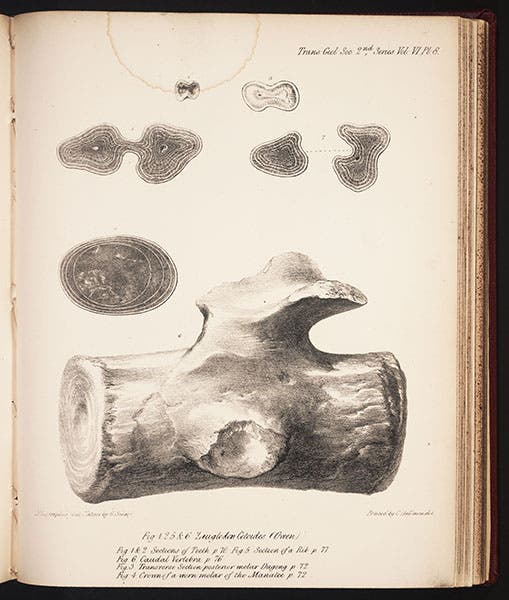

In the early 1830s, he received some fossil bones from a judge in Louisiana; the package contained a fragment of an upper jaw (second image), a single large vertebra (third image), and a leg bone. Harlan thought the bones were the remains of a 100-foot-long marine reptile, and he named it Basilosaursus, “king of the lizards”. In 1838, he took the fossils to London and showed them to the Geological Society of London (GSL) and noted anatomist Richard Owen. Owen was permitted by Harlan to section some of the teeth and came to the conclusion that the teeth, some of which had two roots, were more mammalian than reptilian, and within the mammals, most closely resembled the teeth of small cetaceans. Harlan was convinced and allowed Owen to rename it: Zeuglodon cetoides, the "yoke-toothed whale-like animal", which Owen did in a paper read to the GSL in 1839 and published in their Transactions.

Unfortunately, renaming a specimen is not permited by the zoological powers, even if the original namer consents, so we still call it Basilosaurus. But we recognize that Owen was correct in supposing that Basilosaurus was an ancestral whale. A specimen (not the fragmentary one that Harlan and Owen studied) was on display in Smithsonian Natural History Museum in 1912 (fourth image), and I believe it is still there, in the new ocean exhibit.

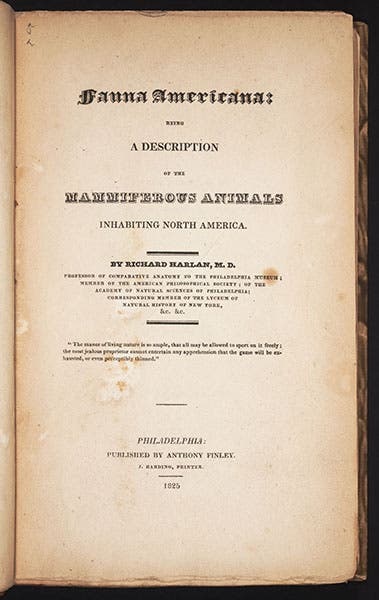

Harlan's Fauna Americana is not a very impressive work to the casual reader, because it has no illustrations. But it was the first American publication to fully embrace the binomial nomenclature system of Linnaeus, so that every animal, such as the grizzly bear, was referred to by its generic and specific name together: Ursus horribilis. We acquired this work in 2011 (fifth image).

The book may be image-less, but it is filled with puckish asides about the world of mammals, and mammologists, which makes it well worth reading. Harlan began his book (as had Linnaeus) with the primate order, and in North America, there is only one primate: Homo sapiens. Here is what Harlan had to say of Homo sapiens: "Inhabits all parts of the earth, omnivorous, disputing for territory; uniting together for the express purpose of destroying their own species." It is hard not to like Mr. Harlan.

The only portrait we have of Harlan is an aquatint in the collections of the National Library of Medicine (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.