Scientist of the Day - Richard Birdsall Rogers

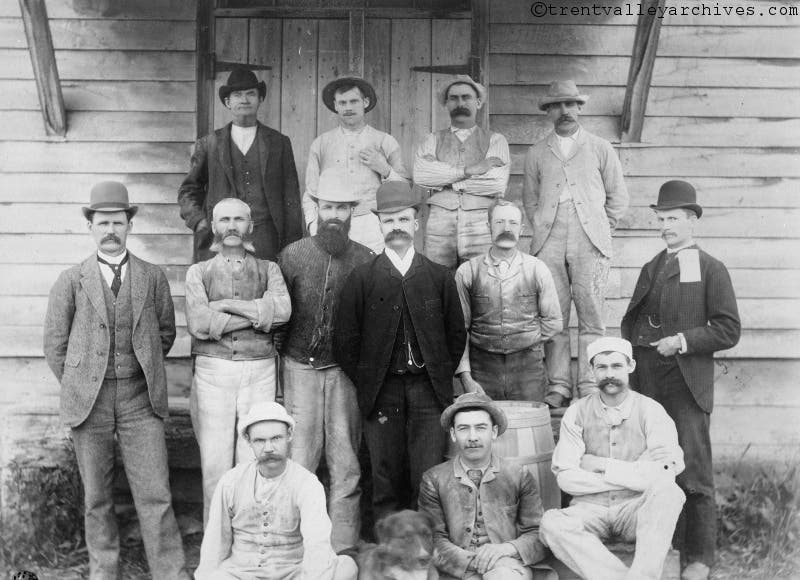

Richard Birdsall Rogers, a Canadian engineer, was born Jan. 15, 1857. Rogers graduated from McGill College in Montreal with degrees in mechanical and civil engineering; in 1884, after working his way up the ladder, he was appointed Superintending Engineer of the Trent Valley Canal, which position he held until he retired in 1906. The Trent Valley Canal was part of the proposed Trent-Severn Canal System, which was intended to connect Port Severn on Lake Huron with Trenton on Lake Ontario, bypassing Lake Michigan and Lake Erie. Much of the 240-mile system used natural waterways, which reduced the number of locks and man-made canals needed. The first lock was built in 1833; the project dragged on for decades, picked up pace with the Confederation of Canada in 1867, and proceeded intermittently thereafter, spurts of activity coinciding with campaigns for political elections. The project would finally be completed in 1920, utilizing 44 locks.

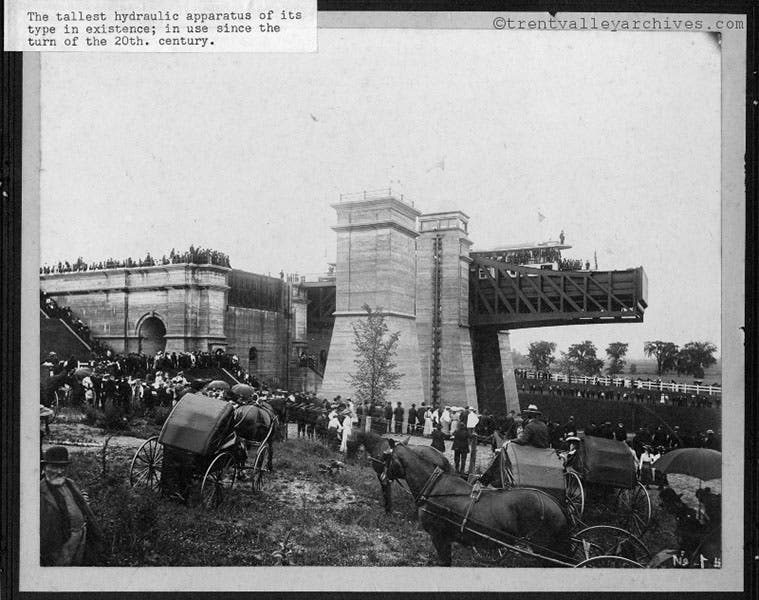

One the bottlenecks was at Peterborough, Ontario, where there was a sixty-five-foot drop in the waterways and no room to install the dozen or so locks it would require to move boats conventionally from one waterway to the next. Rogers was asked for his opinion, and he suggested a boat lift. Several boat lifts had been built in the previous twenty years, most notably the first such device, the Anderton Boat Lift in England, opened in 1874, followed by others in Belgium and France. A boat lift was an elevator for boats; a boat would be ushered into an open-ended caisson full of water; the caisson would be closed and then hoisted the necessary distance, whereupon the other end of the caisson would be opened and the boat could float out. Ordinarily this would require an enormous amount of power, but if you have two lifts operating simultaneously, one going up and the other down, so that they balance each other, then no external power is needed at all, except small engines to open valves and gates and provide compressed air, and these can be driven by water.

Rogers went to Europe to educate himself in the latest boat-lift technology, but he actually designed the Peterborough lift before he went on tour. One of his novel ideas was to build the superstructure needed to guide the caissons out of concrete, instead of wood or iron. He even invented his own concrete mix for the construction. He planned to use 145-foot long steel caissons, poised on 7.5 foot-diameter steel rams that in turn moved up and down in two huge 75-foot long hydraulic cylinders that were buried in the ground. Unlike conventional locks, no water would be wasted at all in the lifting process.

Construction of the Peterborough Lift Lock, as it was called, began in 1896 and was completed in 1904; it officially opened on July 9 of that year, to the cheering of thousands of Canadians. It was the largest unreinforced concrete structure in the world, and the highest boat lift as well. One of the ingenious features of Rogers’ design is that the upper caisson stops just short of the upper canal, ensuring that some water (one foot’s worth) will pour in and make it heavier, tipping the balance of weight and ensuring that the upper caisson will then descend, and drive the other caisson up. The entire structure is one of the triumphs of modern civil and mechanical engineering, or so said the American Society of Mechanical Engineers in 1987, when they declared it a Historic Engineering Landmark.

Rogers went on to design one other lift lock for the Trent Canal, the Kirkfield Lift Lock, completed in 1907. He was not around to see it open, as he was removed from office after a change of government in 1906. He had avoided being a political football in previous years by refusing to reveal the details of the Peterborough design, which made him irreplaceable. But an engineer in a political environment can be irreplaceable just so long, and once the Kirkfield Lift Lock was under construction, his tenure was doomed. His forced retirement was messy, with accusations of impropriety made, but eventually Rogers cleared his name and restored his reputation.

By the time the Trent-Severn canal system was completed, commercial shipping had outgrown it, but the canal system has become very popular with pleasure boaters, and both of Rogers’ lift locks are still in regular use. You can see a video of the Peterborough Lift Lock in operation here.

I find it interesting, if entirely coincidental, that two of Canada's national heroes are both named Rogers – our Richard Birdsall, and the beloved, socially conscious, too-young-to-die-so-soon troubadour, Stan Rogers. They should have a Rogers festival at Peterborough. Or perhaps they have, and I was not informed.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.