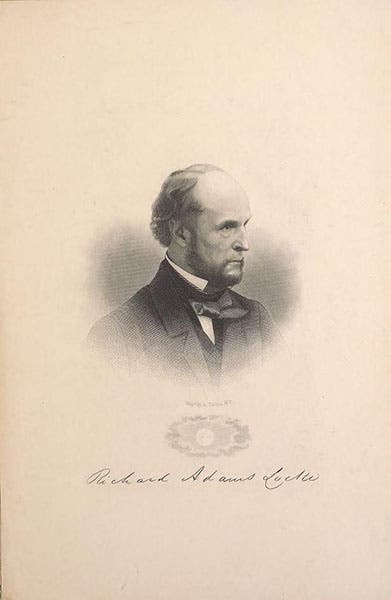

Scientist of the Day - Richard Adams Locke

On Aug. 25, 1835, the New York Sun, a fledgling newspaper less than 2 years old, ran a front-page story, headlined "Great Astronomical Discoveries lately made by Sir John Herschel," in which it was revealed that the famous English astronomer, with a wonderful new telescope mounted in South Africa, had discovered life on the moon. The telescope, which is described in detail in the first column, was some 24 feet in diameter and could magnify objects 42,000 times, thus revealing the most minute features of the lunar landscape. The series continued the next day, and the next, with each new column introducing newly-observed and bizarre lunar creatures, such as unicorns, and bipedal beavers that cradled their young in their arms while walking about. The most dramatic revelation came in the fourth-day’s column, when it was revealed that Herschel had seen human-like creatures flying about the moon on bat wings. He gave it the name: Vespertilio-Homo, or man-bat.

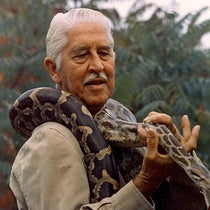

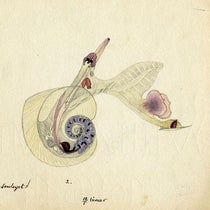

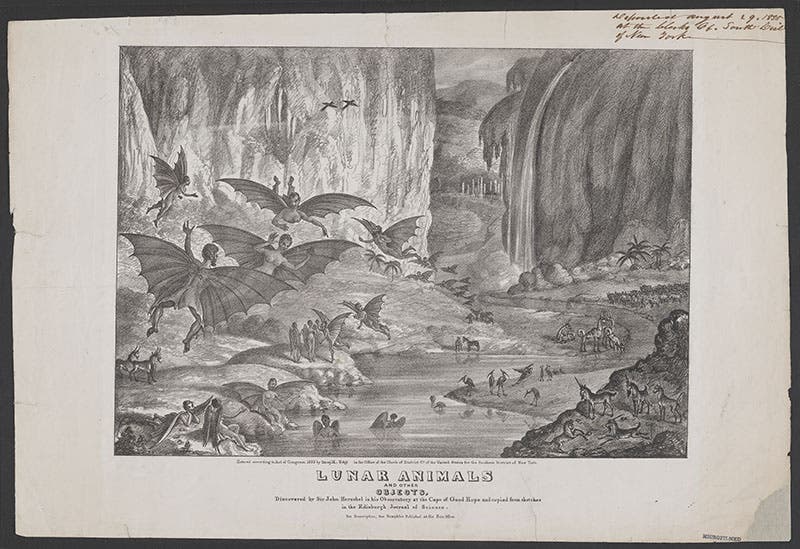

The reports were published anonymously, but we know that they were composed by a writer at the Sun, Richard Adams Locke, for the purpose of satirizing contemporary fascination with life on other worlds, and to boost circulation of the paper. The episode is always described as the "Great Moon Hoax," but it was not really a hoax, in that it was never intended to mislead people, but rather to make fun of them. Nevertheless, many did believe, and after the series had run its 6-day course, it was quickly republished separately, in pamphlet form, in a variety of languages, and sold to an eager public. In the Linda Hall Library, we have two Moon Hoax pamphlets in English, two in French, two in German, and one in Italian, all but one of them printed in 1835 or 1836. One of our English pamphlets has a double-page woodcut showing some of the bat-men (first and third images). Otherwise, there are no illustrations in the remaining tracts, nor were there any in the original newspaper series. But it seems that, when the columns were reprinted, the Sun offered several lithographs for sale separately, which were much more detailed and dramatic than our woodcut. We show one of them here, from the Library of Congress (fourth image). It is often reproduced, usually accompanied by a statement that it was part of the original set of newspaper columns, but it was not.

One of the clever features that gave the stories plausibility is that the Sun claimed they were being reprinted from a Supplement to the Edinburgh Journal of Science, which was known to be a respectable journal to educated Americans, who however probably did not know that the Journal had ceased to publish, at least under that title, in 1833. Also, John Hershel was a well-respected astronomer, who had indeed just taken a large telescope to South Africa (which you can see as the first image at our post on Herschel), which not only added further plausibility, but also ensured that Herschel would not hear about the series, and could issue no denials, until long after the series was over. When Herschel did learn was going on, he would indeed sputter for a while, incredulous that anyone would believe such patent hogwash, but eventually he accepted the humor of it all with good grace. He was, after all, not the one who was being satirized. The object of fun was a Scottish clergyman and popular science writer, Thomas Dick, who had published several books claiming that the universe is brimming over with life, and that all the planets and their moons are inhabited.

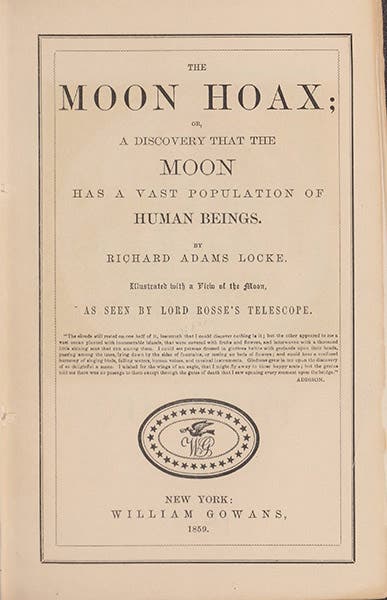

Most of the 1835-36 republications, although they didn’t say so, were drastically condensed. The first edition we have that reprints all six columns in their entirely is one published in 1859 (fifth image), that we just happen to have scanned and made available online, if you would like to read the full text. The man-bat makes its appearance on page 36 of the 68-page book. We also have the 1835 16-page pamphlet online, the one with the centerfold woodcut, if you just want to read the juicy parts.

The Smithsonian Libraries has an 1836 Italian publication containing 6 colored lithographs depicting the newly discovered lunar creatures. They displayed it in their exhibition, Fantastic Worlds, in 2017, in the “Infinite Worlds” section, which you can find here. Scroll down a few pages until you come to the image we have reproduced above (our sixth image). Just below are thumbnails for the other 5 lithographs. Then you can scroll back up and read their account of Locke’s “Moon Hoax.” Thanks to Leslie Overstreet of the Smithsonian Libraries for steering me to the exhibition, which must have been wonderful, and still is, online.

The New York Sun never publicly confessed that the series was a work of fiction, and it wasn’t until five years later that Locke admitted in a private letter that he had made up the entire narrative. It lived on as fact for a long time in many public arenas. As for what Locke did as a follow-up, I have no idea. All I know is that he died on Feb. 16, 1871, and is buried in Silver Mount Cemetery in Sunnyside, Staten Island. I have found no photograph of his grave.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“A view of the inhabitants of the Moon, as seen through the telescope of Sir John Herschel," woodcut centerfold in The History of the Moon. or an Account of the Wonderful Discoveries of by Sir John Herschel, [by Richard Adams Locke],1835 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/f210e32e-d871-43aa-beea-c98a61b78ee2/locke1.jpg?w=534&h=582&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![“A view of the inhabitants of the Moon, as seen through the telescope of Sir John Herschel," woodcut centerfold in The History of the Moon. or an Account of the Wonderful Discoveries of by Sir John Herschel, [by Richard Adams Locke],1835 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/e1bbf0fc-ad4b-463d-90dd-202cb44f09b8/locke1.jpg?w=761&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Detail of first page of The History of the Moon, or an Account of the Wonderful Discoveries of by Sir John Herschel, [by Richard Adams Locke], 1835 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/c865c5d5-e6ee-4532-a38d-24ca214fef33/locke3.jpg?w=714&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Life on the moon according to John Herschel [and Richard Adams Locke], colored lithograph, Leopoldo Galluzzo, Altre scoverte fatte nella luna dal Sigr. Herschel, 1836, Smithsonian Libraries (library.si.edu)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/f04bbb56-4ab9-4c56-a2ee-08a3d6c384eb/locke6.jpg?w=482&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)