Scientist of the Day - Riace Bronzes

On Aug. 16, 1972, an Italian chemist, Stefano Mariottini, was diving off the coast of Riace in southern Italy, when he found two bronze statues on the sandy seafloor, apparently the casualties of an ancient shipwreck. The statues, which depict two nude male warriors, were left undisturbed and declared to the proper cultural authorities, and they were hauled from the bed of the sea a few weeks later. After nine years of restoration and preservation, they were put on public display in the National Museum of Magna Grecia in Reggio Calabria, near the Strait of Messina that separates the Italian peninsula from Sicily. Magna Graecia (greater Greece) is the ancient Greek name for this area of southern Italy.

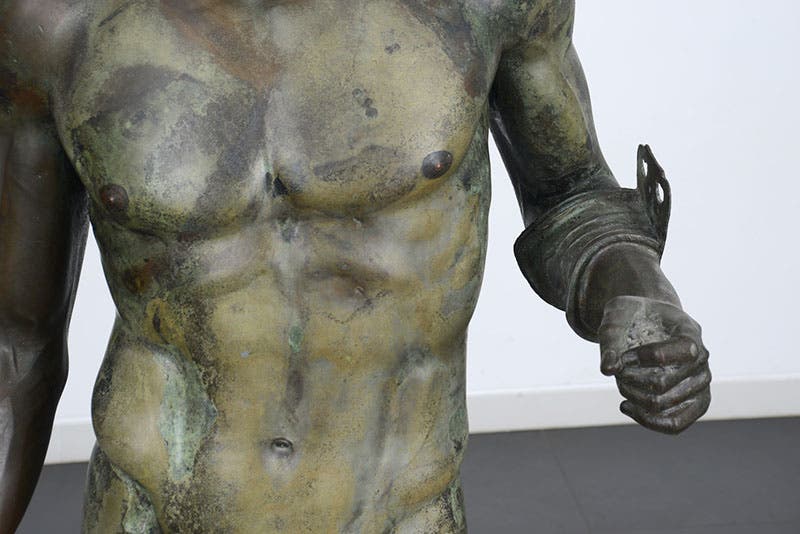

The statues are stunners. Slightly larger than life (the taller is almost two meters high), they differ slightly in their posture and finish, so that one can learn to tell them apart with a little practice (they are referred to, somewhat prosaically, as A and B), but they both have that easy contrapposto pose that was just starting to replace the more severe Archaic poses about 450 BCE, which is when the oldest of the two Riace bronzes is thought to have been fabricated. They were undoubtedly made in Greece – Argos is thought to be a likely location of manufacture – then placed on a ship headed for a wealthy buyer in Magna Graecia, which then sank, through circumstances unknown.

The Riace bronzes are without doubt exquisite works of art – among the finest Early Classical sculptures produced by the Greeks – but we include them here because they also represent a triumph of technology. The statues were produced using the technique of lost-wax casting, which was being employed to produce other, usually much smaller, bronze artifacts about this time. The statues would have been modelled in wax over a clay core, then encased in an outer skin of clay, with internal supports so that the entire clay sandwich could be heated to harden the clay and allow the melted wax to run out, leaving behind a space about 0.3 inches thick that could be filled with molten bronze (90% copper, 10% tin) to form the statue.

A represents a slightly younger warrior, his glass eyes still in place. He originally had a helmet, spear, and shield. B is more laid back, with hollow eyes, and appears older than A; he too once had a helmet, shield, and spear. Both figures have lips and nipples of inlaid copper.

Two thousand years later, Renaissance bronze artists such as Donatello and Benvenuto Cellini struggled mightily to master the techniques of lost-wax casting on a large scale. It would have staggered them to learn that full-size statues such as Riace A and B had been coaxed from wax and bronze at such an early time in Greek history. Heck, it staggers us today to comprehend what these ancient artisans accomplished.

The National Museum of Magna Grecia in Reggio Calabria should be on your must-visit list if you ever plan a trip to Southern Italy. Should you get up to Rome on the same trip and into the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme venue of the National Roman Museum, to see the Boxer at Rest, you will have encountered the three most exquisite specimens of ancient bronze-casting that survive. We will try to do a post on the Boxer at Rest sometime soon.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.