Scientist of the Day - René Descartes

René Descartes, a French natural philosopher, was born Mar. 31, 1596. Many accounts of early modern science give Descartes short shrift, in scrambling to get from Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, and Francis Bacon to Robert Boyle, Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton. But Descartes was arguably as important as any of them in his insistence on a mechanical natural philosophy, where only matter in motion has any explanatory power. In a post on Descartes some years ago, when this series was just getting started, we discussed his vortex theory of planetary motion, which offered a novel explanation of the mechanics of our solar system. We should have returned to Descartes before now, but we haven’t, so we have some catching up to do. Today we are going to look at Descartes’ proposed explanation of the evolution of the earth. Since no one before Descartes had entertained the notion that the Earth might have evolved, this was a daring idea. And when we look at what ensued, it was clearly an idea whose time had come.

Portrait of René Descartes, engraving, Les hommes illustres, by Charles Perrault, vol. 1, no. 59, 1696 (Linda Hall Library)

Nearly everyone before Descartes who considered the Earth as a physical object took it for granted that the Earth we live on was more or less the Earth that God created some 6000 years earlier. The original Earth had mountains, oceans, and rivers where they are now, and the crust, where we now find ores, minerals, and pockets of lava, was pretty much the same as the crust that hosted the Garden of Eden. Descartes had no preconceptions about the Earth’s history. But some conclusions came out in the wash when he pondered the physical makeup of the solar system.

As we discussed in our first post, Descartes concluded from first principles (the principles of matter that he had deduced) that the solar system is a giant vortex of invisible second matter that sweeps around larger chunks of third matter (the planets, including the Earth). At the center of the vortex is the Sun (if you are talking about our vortex) or a star (if some other vortex), which is predominantly first matter, the finest matter of all. The Sun radiates light, in the form of pressure of second matter, and this pressure gives shape to the vortex. However, Descartes knew (from Galileo) that the Sun has spots, which must be bits of third matter that collect on its surface, and over time they would gradually cover the entire surface, leading to collapse of the vortex. The darkened star would then be cast from vortex to vortex (visible as a comet) and will eventually be caught up in a vortex and settle into an orbit. The dying star has become a planet.

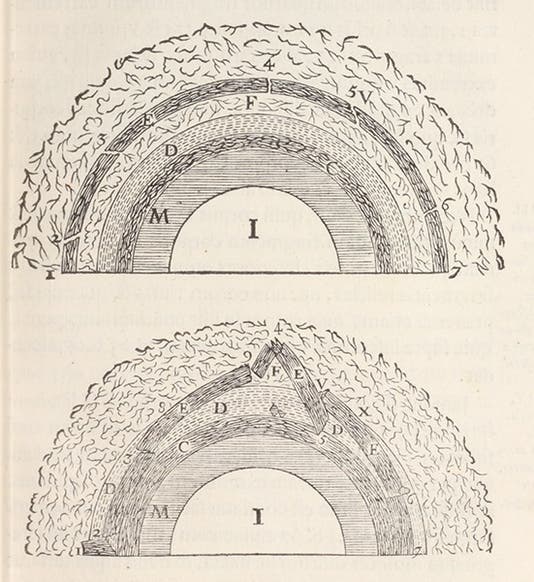

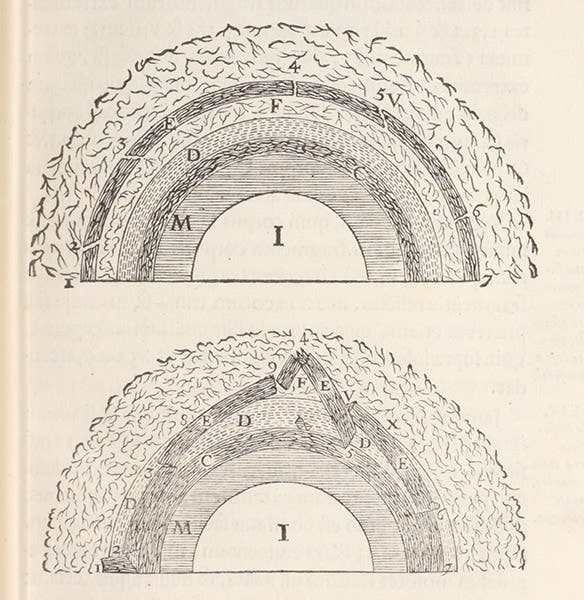

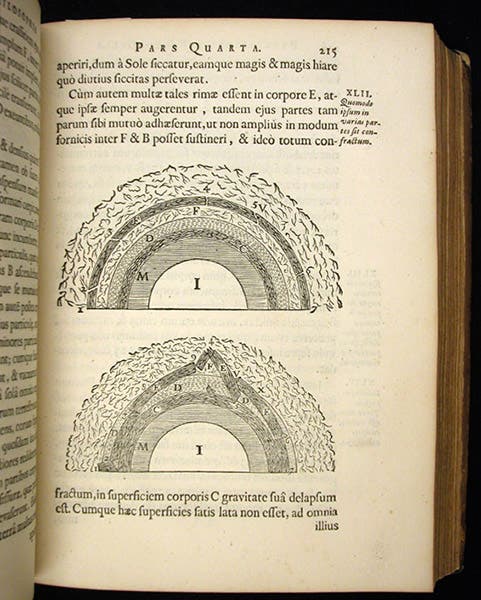

If planets like the Earth were originally suns, then they have changed over time. In his Principia philosophiae (Principles of [Natural] Philosophy, 1644), Descartes attempted to reconstruct the process. We show two versions of a pair of explanatory woodcuts from that book, the proto-Earth, a newly cooled star, at top, and the cooled and altered Earth at the bottom. The Earth started out hot, and formed a crust as it cooled, with many layers of gases, fluids, and solids. As it cooled further, the crust would have dried and cracked, allowing the gases to escape, and causing the crust to collapse, forming mountains, valleys, and ocean basins. The waters within would also have escaped and filled the basins, producing continents separated by oceans. The present-day world was the result of a mechanical process of cooling and collapse.

Descartes was not a geologist and did not pretend to be one, so he gave no account of the formation of strata, as Nicolaus Steno would attempt in 1669. And Descartes’ theory of geogenesis was totally ignored by Athanasius Kircher in his Mundus subterraneus (1665). But when Thomas Burnet in 1681 attempted to reconcile the creation account in Genesis with a more mechanical explanation, it was Descartes’ proposal of a cooling, cracking, proto-Earth that he chose to reconcile with Scripture. Burnet’s book, Telluris theoria sacra (1681-89 in Latin; 1684-90 in English as The Theory of the Earth) immediately found critics and defenders, and for the next 150 years, scores of “theories of the Earth” were published. We mounted an exhibition at the Library in 1984 in which we displayed 53 such books and described 57 more, all published before 1830 and all in our collections (fifth image). The very first book in the exhibition, the one that started it all, was Descartes’ Principles of Philosophy, and the book was opened to the pair of woodcuts we have shown and discussed today. That exhibition was never available online, but the catalog had been digitized and is available as a pdf. The entry for Descartes’ Principia begins on pdf p. 10 of the 72-page catalog.

The portrait of Descartes that we include (second image), an engraving after a painting by Frans Hals, is from a portrait book in our collections, Les hommes illustres, by Charles Perrault (1696-1700). We have published a post on Perrault in which you can see a full-page version of the Descartes portrait (third image at the link).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.